True Sex: The Lives of Trans Men at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

True Sex: The Lives of Trans Men at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

by Emily Skidmore

NYU Press. 272 pages, $27.

IT OFTEN COMES as a bit of a surprise to discover that, before Kinsey or Stonewall, there was any decency shown toward anyone who lived under the LGBT umbrella. But, argues Emily Skidmore in True Sex, some trans men around the turn of the 20th century received surprisingly sympathetic and thoughtful press coverage as well as community support, a pattern that lasted until the 1940s.

There were rules, however, about who received acceptance and understanding and who was labeled as deviant. As ever, whiteness had its privileges. Skidmore contends that a trans man’s “Caucasian” identity, coupled with his presentation of traditional masculinity, often had the effect of “rendering queerness unexceptional.” For example, the town press may have been open to a fluid definition of gender if a local boy turned out to be genetically female, but only if the person in question met certain criteria, such as being “white, middle class, able-bodied, and economically productive.” What the press and the public could not abide was any element of foreignness or difference, especially if it involved race or national origin.

Marriage laws were being “strengthened” in the late 1800s and early 1900s to “protect the institution.” (Skidmore calls the early 1900s the “heyday of marriage legislation,” something to give us pause.) But trans men were, at the same time and in notable numbers, procuring marriages with women. They were not necessarily suspect, as the marriage was ostensibly a heterosexual union and did not overtly upset the dominant social order. They did attract opposition when they disturbed social norms in some other way, such as an interracial marriage. Possibly the most disturbing conclusion in the book is that trans men of color, being reliably labeled as deviants, actually made it possible for white trans men to live respectably in their communities.

But if local press treatment was often fair-minded, national press coverage was more sensationalistic and often acted to diminish this support. Once the story spread beyond local borders, essentially pressuring a locality to crack down on its deviants, the latter were redefined as a threat to the community rather than an asset.

Skidmore also examines the contrast between the new breed of “sexologists” and the local press during this era. While sexologists were willing to pathologize anyone who strayed from gender norms, the press was admirably less willing to accept these diagnoses (again subject to criteria of race and gender-related behavior).

There are other intriguing propositions in the book. Based on the journeys of people such as Frank Dubois and George Green, Skidmore suggests that trans men did not necessarily seek typical geographical enclaves of queerness, such as San Francisco, or even think it necessary to do so. In fact, most of the trans subjects featured in the press during that period lived either in rural regions or small metropolitan areas not known for harboring queer communities, places like Salt Lake City or Bangor, Maine.

Skidmore also argues that studying LGBT people as a single unit tilts historians toward drawing universal conclusions. But that approach often misses the anomalous and the unexpected, such as the experience of many trans men a century ago or more. Each subgroup, she argues, needs to be studied on its own terms.

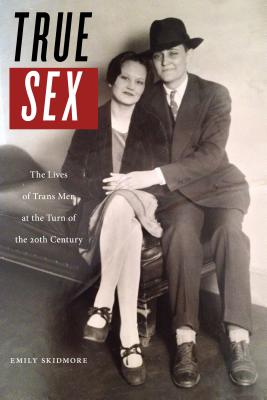

The language of True Sex does have an academic rigidity in places, and its structure can be as formulaic as a doctoral dissertation. Thus, for example, each chapter in the book, as well as the book as a whole, has a formal introduction and conclusion. And there are (eek!) sixty pages of endnotes and bibliography. Still, most of True Sex will probably be accessible to general readers who are interested in the intricacies of LGBT history. The personal accounts are presented in compelling detail and with compassion, living up to the promise of intimacy suggested by the cover photo of trans man Kenneth Lisonbee and his wife Stella Harper from the unlikely year of 1929.

________________________________________________________

Peter Marino, an English professor emeritus at SUNY Adirondack, is the author of the YA novel Magic and Misery.

Odd Pocket of Tolerance

This article is only a portion of the full article. If you are already a premium subscriber please login. If you are not a premium subscriber, please subscribe for access to all of our content.

This article is only a portion of the full article. If you are already a premium subscriber please login. If you are not a premium subscriber, please subscribe for access to all of our content.

0

Published in: March-April 2018 issue.