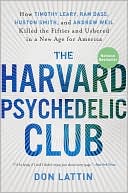

The Harvard Psychedelic Club: How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston Smith, and Andrew Weil Killed the Fifties and Ushered in a New Age for America

The Harvard Psychedelic Club: How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston Smith, and Andrew Weil Killed the Fifties and Ushered in a New Age for America

by Don Lattin

HarperOne. 256 pages, $24.99

TIMOTHY LEARY proclaimed it “the greatest Good Friday in two thousand years.” On the morning of April 20, 1962, the Dean of Boston University’s Marsh Chapel led his congregation in an intense two-and-a-half-hour session of dark poetry, dramatic homily, and somber music about the Passion of Christ. Meanwhile, a clandestine experiment was being conducted in the church’s basement. Under Leary’s supervision, half of twenty volunteers were given the hallucinogen psilocybin, while the rest received a placebo. The purpose of the experiment was to test the drug’s reliability as an entheogen (a psychoactive chemical.)

“The only natural light shines from three tiny stained-glass windows,” writes author Don Lattin in his description of the womb-like setting, “including one depicting Jesus holding an open Bible.” While half of the divinity students remained calmly in their pews, the others began crawling around on the floor or meandering in ecstatic bliss. “God is everywhere!” exclaimed one seminarian, while another escaped from the house of worship and ran down Commonwealth Avenue, trumpeting the dawn of a Messianic millennium of universal peace.

Huston Smith, a Methodist minister, MIT philosophy professor, and author of the best-selling The World’s Religions, was a pre-selected guide for the test and among those who received the drug. He later remembered that day as “the most powerful experience he would ever have of God’s personal nature.”

Lattin fills each chapter with mind-blowing stories that make good on the promise of the book’s bold subtitle. By giving birth to the drug-fueled 60’s, the author, a religious journalist, claims that the group “changed nothing less than the way we look at mind, body and spirit.” It’s a bold but highly plausible claim, and Lattin presents a impressive array of evidence concerning the influence of these four men on the Counterculture, which in turn transformed the country’s views on politics, medicine, religion, and culture for decades to come.

The book begins with crossed paths in Cambridge during the fall of 1960. Wife-swapping Leary (whom Lattin calls “the Trickster”) and another Harvard faculty member, the closeted Richard Alpert (“the Seeker”), taught in the school’s Department of Social Relations, where they conducted psychology experiments with mushrooms and LSD. Family-man Smith (“the Teacher”) wrote about the mystic experiences of the great masters but had yet to reach that higher state of consciousness himself. Seeking a fast track to enlightenment, he consulted writer Aldous Huxley, who introduced him to Leary and “the Harvard Psychedelic Club.”

Freshman pre-med student Andrew Weil (“the Healer”) quickly learned about the psilocybin project but was refused participation by Leary, who cited an agreement with Harvard permitting only graduate student involvement. Lattin reports that Alpert became infatuated with Ronnie Wilson, an undergraduate and Weil’s former roommate, and decided to share the synthetic “fruit of the gods” with the object of his attention. When the spurned Weil learned his underage friend had joined the “acid cult” inner circle, “with the zeal of a jilted lover” he spearheaded a damning exposé in The Crimson, leading to the dismissal of both Alpert and Leary.

Media attention on the firings turned the men into instant celebrities. They relocated their research project to Dutchess County, New York, where their work “morphed into an extended family, spiritual commune, religious cult, and finally, social movement.” Alpert had assumed a “maternal, wife-like role” with Leary’s two children, but nonetheless was forced out of Millbrook, the 64-room home where they lived, because Leary took issue with Alpert’s penchant for young men.

After the four central figures disperse, Lattin follows their adventures over the next forty years. He conducted firsthand interviews with Smith, Alpert, and Weil (Leary died in 1996), and many other key players. There’s no doubt that he’s done his investigative homework, yet covering so much history in a relatively short book means that Lattin never dives too deeply into any particular event or person. The storyline moves forward at such a rapid clip that readers may find themselves wishing Lattin would slow down and let them enjoy the groovy trip. It’s a bit unusual to damn a writer for being too entertaining, but this book reads like a novel crafted from the screenplay of an outlandish HBO mini-series—smart, fast, and thought-provoking, with copious amounts of sex, drugs, and intrigue. Cameos placed throughout the book—including President Kennedy, Allen Ginsberg, John Lennon, Grace Slick, Keith Richards, Jerry Garcia, AA founder Bill Wilson, “Unabomber” Ted Kaczynski, even actress Uma Thurman, whose mother was married briefly to Leary—reveal the widespread influence of the foursome. But these appearances can also be distracting, in the same way that major Hollywood actors playing minor roles can interfere with a viewer’s ability to suspend disbelief.

In his life after Leary, Alpert trekked to Katmandu and changed his name to Ram Dass, or “servant of God.” Returning to the States, he dedicated his life to philanthropic endeavors and became one of the most sought-after speakers on the New Age conference circuit.

As the self-appointed messiah for the counter-revolution, Leary’s life would be marked by controversy, particularly after he delivered his infamous mantra, “Tune in, turn on, drop out!” In May 1969, he ran against Ronald Reagan for governor of California, but was sentenced to jail for drug possession. After breaking out of prison, he lived in exile abroad until U.S agents captured him. Lattin believes Leary provoked Nixon’s “War on Drugs” and sparked the conservative backlash of the 80’s.

Weil graduated from Harvard Medical School and traveled to South America hoping to find answers from curanderas. His journey to the folk healers taught him that the answers he was seeking could be found within his own culture—and within himself. As the leading alternative medicine expert, Time magazine named him one of the 25 most influential people in America.

Smith continued to teach and write. His The World’s Religions sold over two-and-a-half million copies, and PBS aired a five-part special about him, The Wisdom of Faith with Huston Smith. A student of Vedanta Hinduism and Zen Buddhism, Smith tried to put those 1960’s experiments in perspective: “the real test of a person’s spirit is the way they live their lives. It’s what happens after the ecstasy.”

Court Stroud lives in New York City, where he teaches a college prep literature course at GMHC’s G.E.D. adult education program.