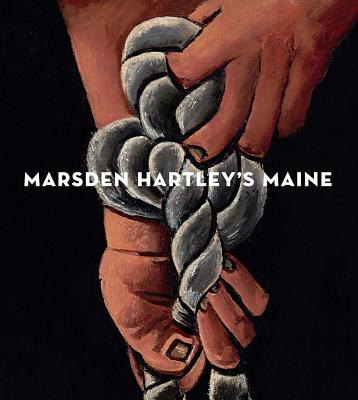

Marsden Hartley’s Maine

At the Met Breuer, New York City

March 15–June 18, 2017

ONE OF THE BEST-KNOWN images of Marsden Hartley (1877–1943) comes to us through the lens of the great gay photographer George Platt Lynes in a photograph from 1943, shortly before Hartley’s death. Hartley slumps in a chair, his body casting massive shadows under the influence of Lynes’ harsh lighting. Hartley’s most marked (and remarked upon) physical feature—his large, liquid eyes—appear haunted, his head resting heavily on one hand.

Photographic historian Allen Ellenzweig draws a connection between subject and photographer, as Lynes had recently lost his lover George Tichenor during World War II. Hartley, for his part, had experienced the death of a beloved World War I German officer, which inspired his most famous works, a series of abstract, symbolic object-portraits known as the “Berlin” paintings. In the background, a young male model leans against the wall just outside Hartley’s shadow, echoing the dual loss.

The Lynes photograph is remarkable, but it is only a partial truth. Hartley’s melancholy nature never left him, but by 1943, he was not likely to be seen wearing a suit, cigarette in hand, in a New York photo studio, the picture of an urban(e) if rumpled artist. And yet, there was a time when this image would have been appropriate. Let’s go back to 1909, when Hartley met famed photographer Alfred Stieglitz and soon had his first show at Stieglitz’ pioneering 291 Gallery. Living in New York City, he became a leading Modernist painter with works in the 1913 Armory Show and exhibitions at various galleries. He pursued a variety of artistic styles, from a version of Post-Impressionism to pure abstraction before developing a unique style that combined realistic subject matter—mostly figurative or landscape—with an often dreamlike intensity. Frequently on the move, Hartley had significant sojourns throughout his career: in Berlin, Bavaria, Paris, Mexico, New Mexico, Bermuda, and Massachusetts. But he always returned to New York.

After all that, he chose to go home to Maine in 1937, where he painted a variety of the state’s archetypal features in scenes of mountains, waves, rocky coastlines, lighthouses, and threatened industries like logging and lobster fishing. These are the years in Hartley’s career—along with an early period around 1910 that was similar thematically, if not stylistically—that are emphasized in the 2017 exhibition Marsden Hartley’s Maine, which was held at the Met Breuer in New York City and at the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine. The show and its accompanying catalog are impressive achievements in that they manage to hint perceptively at Hartley’s massive range of styles and subjects, even while restricting themselves to selections from his years in Maine.

Although his very earliest paintings—direct portrayals of the woods and of Walt Whitman’s house in Camden—are straight realism and use restrained colors, Hartley quickly adopted the Italian Giovanni Segantini’s stitched brushstroke, whereby threads of contrasting colors create rich textures when laid down side-by-side. His depictions of Maine’s mountains and foliage using this method are riots of color, from bright yellows to deep purples. They have not always impressed critics—Clement Greenberg referred to them dismissively as a “fling at the high palette of the later impressionists and of the fauves”—but their visual verve dominates the Met Breuer exhibit’s early rooms.

At the opposite extreme, Hartley’s “Dark Mountain” pictures foreshadow the onset of stylistic changes. The subject matter is still realistic, but the colors are muddy, and abstracted tree trunks loom and sway over tiny farmhouses. Scholar Jonathan Weinberg points out that Stieglitz, Hartley’s longtime dealer, once said that Hartley contemplated suicide during the painting of the “Dark Mountain” series, and no other paintings in Hartley’s career are as obviously emotionally turbulent. By the time of such works as Landscape No. 14 (1909) and Desertion(1910), bright colors and obvious representationalism had lost ground after a brief period of dominance. Even paintings that retain patches of Fauvist color, like Kezar Lake, Autumn Evening or Untitled (Maine Landscape)—two paintings both from 1910—feature rapid, dense, smeared brushwork that push Hartley toward the abstract.

While Hartley followed this road to purer abstraction—as can be seen in the critically acclaimed Berlin sequence partially inspired by his German lover’s death—he returned to the representational later in his career. Hartley spent time in Nova Scotia in 1935 and 1936, boarding with the Mason family, whose two sons Hartley was certainly in love with and whom he memorialized in a series of paintings following their tragic drowning deaths in a boating accident. This period was followed by his full-time return to Maine, where he settled in Portland before moving around the state to live and work in his final six years.

His return seems partly motivated by the benefits it could have for his painting career, though Hartley also identified deeply with the Maine landscape. As a career move, an emphasis on regionalism in the 1930s art world also made “rootedness” a virtue. Hartley positioned himself as “the painter of Maine,” with his most famous late sequence featuring the

imposing bulk of Mount Katahdin juxtaposed against the ephemeral tableaux of the shifting seasons. Writing in the show’s catalog, Randall R. Griffey proposes that this “recurring focus in the late work on permanence and monumentality … evokes Hartley’s own aspiration to achieve high stature and a far-reaching legacy as an artist.” Meanwhile, the seasonal focus may reflect Hartley’s knowledge that his time was fleeting as he became older and suffered regular illnesses. These portraits of the mountain—remote, lonely, and isolated, often presented in rough-hewn, unvarnished wood frames—certainly echo Hartley’s own self-perceptions during this period.

The Mount Katahdin paintings were just some of Hartley’s iconographic views of his native state, many of which emphasize an archaic version of Maine. He often presented life in Maine as he wished it were still being lived rather than as it appeared during the 1930s. In their introduction, curators Donna M. Cassidy, Elizabeth Finch, and Randall R. Griffey write that Hartley “observed Maine as an outsider always returning, as a traveler remembering his birthplace.” This meant that the influence of machines was excised, as when “paintings of woodlots and log drives allude to the lumber industry, with dramatic views of nature touched by workers, but no sign of the mills.” Massive piles of logs are shown next to a simple hatchet (Abundance, 1939-40), a pair of hands grapples with thick ropes (Knotting Rope, 1939-40), or a group of lobstermen cluster near their traps (Lobster Fishermen, 1940-41). These paintings serve to depict an idealized vision of pre-industrialized Maine, a place where hearty, masculine workers struggle with the natural environment.

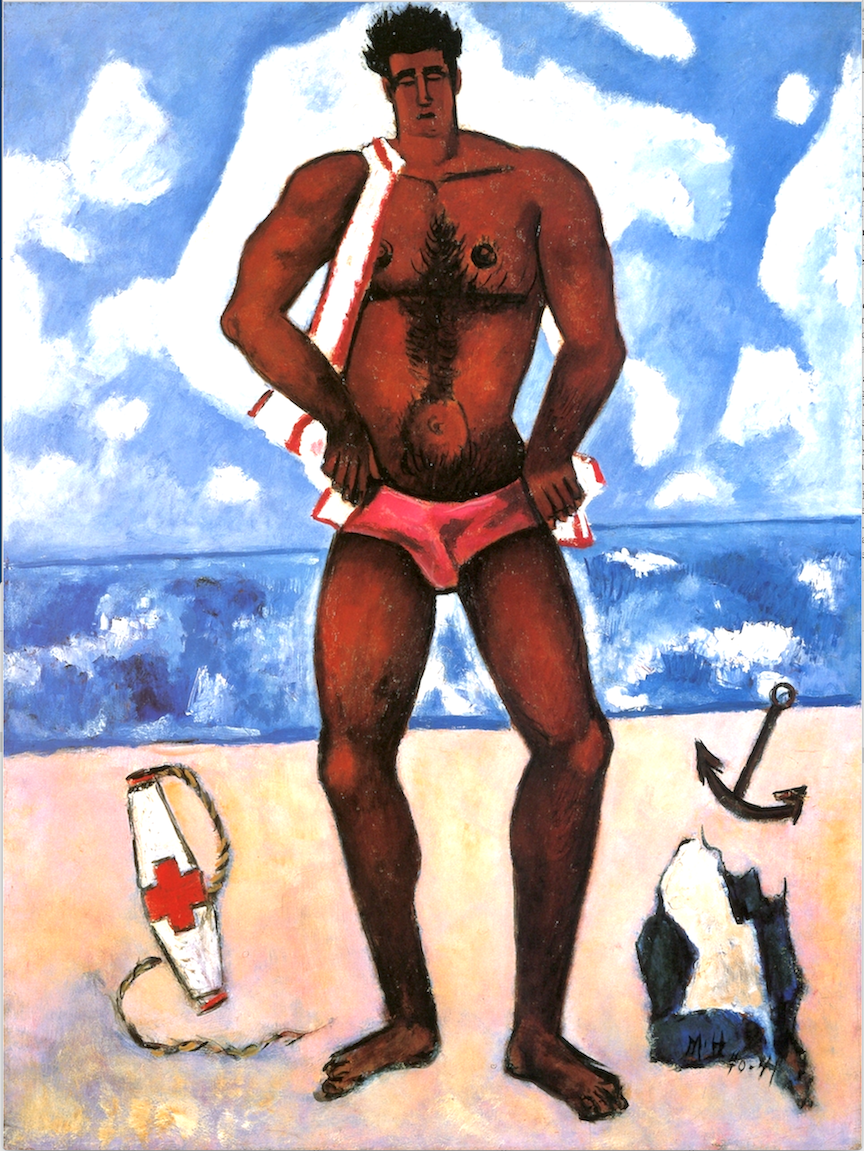

In these works, Hartley profited by being able to include homoerotic elements without attracting negative attention. The ideology of the common man in the 1930s, so often seen in the era’s WPA paintings and murals, helped to mask homoerotic content, subsumed beneath images of manly ruggedness and strength. Contemporary critics referred to his paintings as “masculine,” “primitive,” or “national.” Even paintings tightly focused on the male body, such as the stripped-down boxer of Madawaska—Acadian Light-Heavy(1940), did not provoke comment on Hartley’s sexuality. He benefited from reluctance to address sexuality as a possible element in his work, assuming critics were not entirely blind to it.

Hartley did his part to encourage this critical reaction. For example, ignored his model William Moonan’s built but slim physique, instead turning him into the bear-like, aggressively muscled and masculine Flaming American (Swim Champ) (1939-40). Paul Cezanne’s Batherwas an obvious prototype for Canuck Yankee Lumberjack at Old Orchard Beach(1940-41), but Hartley’s depiction is bulked-up, tanned, hirsute, and transformed into a monumental representation of an American worker—even while wearing nothing but skimpy bathing trunks. In paintings like Young Hunter Hearing Call to Arms(1939) and Down East Young Blades(1940), Hartley created simplified, stylized versions of New England folk types. These paintings allowed him to focus on male bodies while taking advantage of the patriotic cover provided by his glorification of working men and their labors.

Although the vast majority of the works on display are landscapes, and the exhibit’s focus on Maine did not permit inclusion of the Berlin officer paintings, Marsden Hartley’s Maine addresses his homosexuality throughout. While much of the work on display was inspired by the outdoor scenes of his region, he also had a fondness for painting young men in their element—outdoors, often in abbreviated attire or almost nude. Indeed, the “coverboy” for this exhibition, Canuck Yankee Lumberjack, shows one such man in his prime, who seems to be taking a day off at the beach, clad only in a brief bathing suit. The influence of Hartley’s sexuality is particularly noted on his late male semi-nudes and paintings inspired by the death of the Mason brothers. The catalog notes Hartley’s self-identification with the models he employed, giving them his own deep blue eyes, as is especially pronounced in Young Seadog with Friend Billy(1942). Thus as he neared his life’s end, Hartley found an imaginative way to become one of the manly young workers who populate much of his late output.

Even during his period of greatest success following his return to Maine, Hartley was never convinced that his work was adequately appreciated. Constant complaints to Stieglitz about slow sales were a major factor in the end of their business relationship in 1937. The move to Maine enhanced his fame, inducing museums such as the Metropolitan and the Whitney in New York and the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., to purchase significant works, but it also displaced him from the center of the art world in New York City and added to his feelings of loneliness and bitterness. Nevertheless, whatever his personal struggles, he was vital artistically to the very end. His death in 1943 at age 66 prevents our seeing how an artist who was often one of the most experimental pre-World War II American painters might have adapted to the drastic shifts of the postwar period. The trajectory of his work as seen in Marsden Hartley’s Mainesuggests he would have navigated this new world with depth and intelligence.

Philip Clark is at work on a biography of gay publisher and First Amendment pioneer H. Lynn Womack.