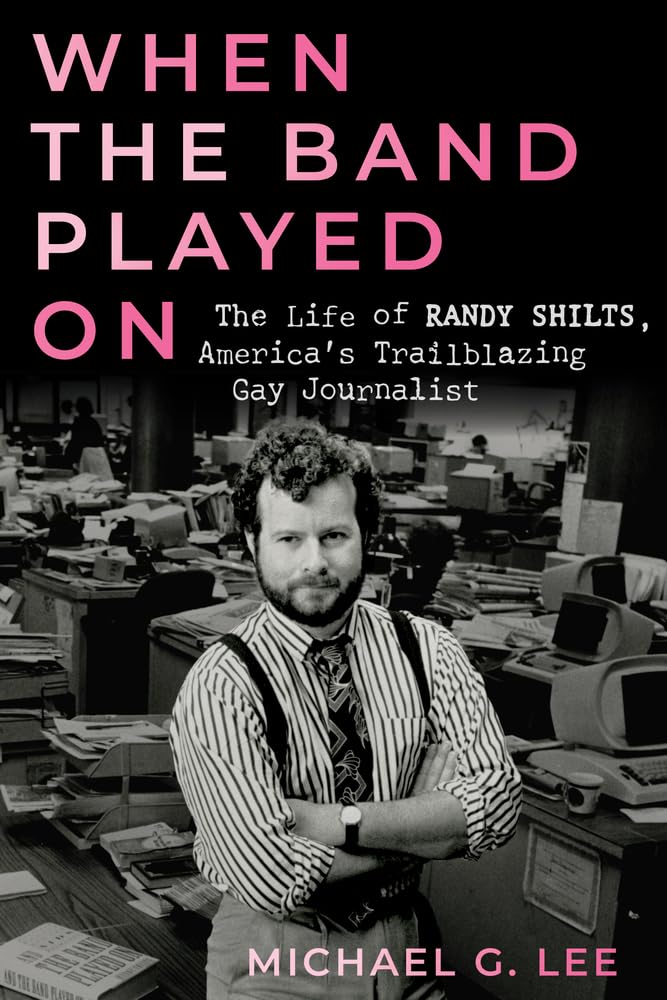

WHEN THE BAND PLAYED ON

The Life of Randy Shilts, America’s Trailblazing Gay Journalist

by Michael G. Lee

Chicago Review Press. 373 pages, $30.

MICHAEL G. LEE begins his new biography of trailblazing gay journalist Randy Shilts with a 1970s San Francisco incident. Shilts meets a trick at a leather bar on Folsom Street and, after their encounter, says to the guy: “I’m one of the most interesting people you’ll ever meet.” After reading Lee’s book, one would be hard-pressed to disagree. Shilts was ambitious, arrogant, insecure, gifted, and at times more complicated than the stories he covered. For all his limitations, he was making history at the same time that he was reporting it.

Shilts became the first openly gay reporter for a mainstream newspaper, San Francisco Chronicle, and the first to cover the queer community full time, writing three seminal books on the subject. The first, The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk (1982), charted the rise of California’s first gay elected official and was also a cultural history of San Francisco in this era. He began covering AIDS for the Chronicle at the start of the pandemic, eventually writing his 1987 bestseller And the Band Played On, in which he indicted the U.S. government’s inaction, the medical establishment’s neglect, and gay organizations’ denial of the crisis in the early years. The book was nominated for a National Book Award and made into an HBO docudrama in 1993. His last book, Conduct Unbecoming: Lesbians and Gays in the U.S. Military, detailed the history of persecution of gay and lesbian service members. The book was central to the 1993 Congressional debate on discrimination in the armed forces, which led to the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” compromise of the early Clinton years.

Shilts learned that he had HIV on the day he finished the manuscript of his last book, though Lee suggests that he might have known earlier. Worried that his illness might overshadow his reporting, and not wanting to be labeled an AIDS activist, he didn’t publicly reveal his illness until February 1993. He died of complications a year later at age 42.

Lee interviewed Shilts’ family, friends, colleagues, lovers, and critics. He makes it clear that his subject had both admirers and detractors, noting that when he gave a speech at the 1989 International AIDS Conference in Montreal, he elicited both boos and applause. But as Shilts was aware, the queer community’s ambivalence toward him went back to articles in the 1970s on out-of-control STD rates, which rankled activists who took this as a broadside against gay men.

Lee interviewed Shilts’ family, friends, colleagues, lovers, and critics. He makes it clear that his subject had both admirers and detractors, noting that when he gave a speech at the 1989 International AIDS Conference in Montreal, he elicited both boos and applause. But as Shilts was aware, the queer community’s ambivalence toward him went back to articles in the 1970s on out-of-control STD rates, which rankled activists who took this as a broadside against gay men.

Lee’s slant is therapeutic, depicting Shilts as a kid who experienced an alcoholic mother, a physically abusive father, and bullying at school. “[H]is only friend from sixth grade described how Randy would pause and flinch when his teacher asked a question, almost like he was about to be slapped, [and]he then responded with sarcasm, arrogance, or brilliance.” Between his upbringing and covering AIDS for over a decade, Lee believes that Shilts suffered from trauma, using drugs and alcohol as coping mechanisms. Lee cites the origins of his more abrasive mannerisms (e.g., his famous half-smirk) as defense mechanisms.

After he graduated from college as an acclaimed student journalist in 1975, he took the bold step of presenting himself to prospective employers as openly gay. Being out for Shilts was nonnegotiable. Throughout his career, he sought to expose the lies and myths about LGBT people to straight readers. Lee notes how the mainstream media accepted him as an expert, not only on AIDS but on the gay populace. This insider status gave him a degree of authority that was problematic for the LGBT community, as there were alternative viewpoints to those that Shilts advanced. When he advocated the closing of San Francisco’s bathhouses to contain the spread of AIDS, he was denounced as a hypocrite because he’d worked at a Portland bathhouse in 1974.

In the early chapters, Lee offers an in-depth, graphic portrait of Shilts’ sex life. Shilts had written about his escapades for sex magazines. Lee believes this is critical to understanding who he was and why he chose the subjects on which he reported, quoting extensively from the journals he kept on his sexual adventures. He views this as valuable information about the ways he gained experience, how he felt about himself, and how he wished to find a fulfilling relationship even as he participated in the sex scene.

Shilts was far from perfect in Lee’s assessment: “He was as complicated, vulnerable, and contradictory as many of us would be if we found ourselves in similar circumstances.” He participated in the gay institutions that he criticized—the bars, the bathhouses, gay street life—embodying the incongruities of the era in which he lived. While most of the issues that Shilts grappled with have been resolved—AIDS as a death sentence, LGBT people in the military, participation in mainstream politics—each controversy relates to a broader struggle for human rights that continues to be debated today. Lee contends that oppressive systems tend to recycle the same divisive issues as a way to justify their actions and extend their power. Shilts’ work helps us to better identify these tactics and how to address them.

A month before he died, Shilts wrote a letter to The Advocate, his farewell to the gay community, concluding: “Hopefully, history will record that I was a hell of a nice guy and that the people who have criticized me are a bunch of fools and hypocrites.” As he lay dying, his biggest fear was that he’d be forgotten over time, so he would have been thrilled to know that his image was among the first to be installed on the San Francisco Rainbow Honor Walk near the corner of 19th and Castro Streets, his old stomping ground.

Brian Bromberger is a freelance writer who works as a staff reporter and arts critic for The Bay Area Reporter.