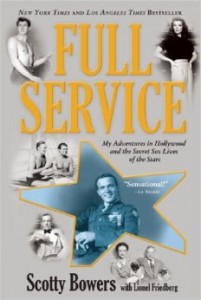

Full Service: My Adventures in Hollywood and the Secret Sex Lives of the Stars

Full Service: My Adventures in Hollywood and the Secret Sex Lives of the Stars

by Scotty Bowers with Lionel Friedberg

Grove Press. 286 pages, $25.

SCOTTY BOWERS’ love affair with movie stars began when he was still a boy whose divorced mother had moved from a failed farm in the Depression Midwest to the city of Chicago, where Bowers not only learned to sneak into movies but earned money for his family the way any hero in a Horatio Alger novel might start out: delivering newspapers, shining shoes, and letting local priests have sex with him. But his memoir, published at the ripe age of 88, really starts when, after leaving the Marines at the end of World War II, he takes a job pumping gas at a gas station in Hollywood—where he learns that some of the customers are willing to pay for more than petrol. Walter Pidgeon was the first. Following Walter, it was one celebrity after another. “Those were wild and wonderful days,” muses the man whose dick was so admired that he would use it to stir cocktails at the parties he bar-tended. “Often just before I drifted off into sleep I would stare up at the ceiling and simply count my blessings, feeling overwhelmingly grateful for my lot in life. There was no doubt about it. Hollywood was simply the most marvelous place in the world for anyone to be.”

And why not? Bowers was handsome, well endowed, in love with the movies and everyone who worked in them.

Of those there were many. From Cary Grant to Olivier and Vivien Leigh, to Edith Piaf, Katherine Hepburn, and Spencer Tracy, his friends were all, judging from this memoir, glad to see him—perhaps because the minute they saw him they thought of sex, perhaps because he was a fan who would cook, clean, mix drinks, listen to people’s woes (e.g., Spencer Tracy) and lend them his dick. Nothing seems to have gotten him down for very long, in fact, though Full Service has its share of horrors: the invasion of Guadalcanal, the death of his brother in combat, the death of his beloved daughter after a botched abortion, the terminal alcoholism of Errol Flynn, Spencer Tracy, and William Holden, and, toward the very end, AIDS, which brought it all to a halt. But who’s to argue with a man’s ability to say, no matter what happens, “Life moves on”? Full Service brings to mind that immortal send-up of all showbiz autobiographies, Patrick Dennis’ Little Me, in which a blithe and imperturbable narrator sails through life no matter what is happening.

The problem with a book like Full Service—or any memoir about the sex lives of famous people—is, of course, one of credibility. Bowers is aware of the problem. He even refutes the rumor that Clark Gable demanded “that fag” George Cukor (who launched Bowers’ career at one of his famous pool parties) be fired as director of Gone With The Wind. This was a story, Bower says, that “someone had planted … in the gossip columns of the Hollywood trade papers simply to undermine George’s reputation.” When Bowers learns that the man writing a biography of Tyrone Powers is going to mention Powers’ sexual predilection for what Bowers calls “the pee and the poop,” he convinces the writer that these stories are hogwash, until the book is published, whereupon he tells the author they are true. Why? “It was still too soon after Ty’s death to be shattering the myth of one of Hollywood’s golden boys,” Bowers writes. “Twenty years after his death Ty was still looked upon as an idol. It was right for us to protect his fans from any disappointment or disgust they may have felt after reading about his old sexual habits.” But now, at the age of nearly ninety, with the subjects all dead, it’s apparently okay.

It’s okay because what Powers did doesn’t bother Bowers. “The truth is that I never cared one iota about how people got their rocks off in private,” he writes, “just as long as they weren’t hurting anybody. We all have our secret preferences and weaknesses, call them whatever you will.” What Tyrone Power “did cannot and will not diminish my fondness for him, his greatness as an actor, or his reputation as one of the nicest people who ever inhabited this crazy place called Hollywood.”

Nevertheless, before long one starts to feel a certain dread when, after each episode closes, the names of the next are introduced—like the tumbrels that accompanied people to the guillotine. Oh no, the reader blanches, not Olivier and Leigh! Yes, Oliver and Leigh—and Tracy and Hepburn (a romance manufactured by the studios, says Bowers, who procured many young women for Hepburn and let Tracy chew on his cock), and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor (both same-sexers), and Clyde Tolson and J. Edgar Hoover (who did drag, according to Bowers, on a weekend visit to California).

The only sin in this book seems to be losing your freedom to sleep with whomever you want—like Paul Novak, a muscle man Mae West acquired toward the end of her life. Novak tried to retain his independence: “still a virile, healthy, horny guy,” Bowers remembers, “but he had to spend most of his evenings with Mae at home eating TV dinners on a tray while watching boring sitcoms. He became a pathetic, fat slob, and simply wasted away. When dear old Mae died in November 1980 it was too late for Paul to start his own life all over again. By then he was a broken, beaten man.”

Bowers, who had a daughter by a woman with whom he shared a home for many years, even while he was out tricking, or having, at one point, an affair with two women he loved, never let himself be tied down. But one wonders: what was everyone feeling? This demimonde of beautiful people, gorgeous weather, exciting work, and available sex partners—was it hell or heaven? Bowers praises the mother of his child repeatedly for tolerating his absences, for never asking questions, even when he goes on, later in life, to marry another woman. Yet feelings are not the subject here; the topic is the endlessly unreeling film of sexual encounters. The paradox, however, is that, having devoured this book the way you eat cashew nuts, you ask: what was the point? We remember these people for their movies, not for what they did in bed.

The ones we’ve already heard about—Randolph Scott and Cary Grant, Tab Hunter, Tony Perkins, James Dean, Montgomery Clift—move by rather quickly. But the others! Soon one is sitting with a very large pile of dirty laundry, though why it’s dirty would be a mystery to Bowers, who says repeatedly that nothing that gives people sexual pleasure bothers him, not even the sandwich that Charles Laughton meticulously assembles in his kitchen while Bowers and the naked hustler he’s brought watch. Having arranged the lettuce, tomato, and buttered bread Laughton needs only one more ingredient—provided by the hustler during a quick trip to the bathroom—after which the lettuce and tomatoes reappear with a light brown smear, leading the hustler to whisper to Bowers the immortal question: “Jesus, why did he even take the trouble to wash the fucking lettuce and tomatoes?”

We may wonder, too, but Bowers has already moved on. There are nonsexual stories: Cole Porter hiding under his dinner table to hear what his guests say about him, Bowers getting ex-King Farouk to donate some of his vast collection of pornography to Alfred Kinsey, Edith Piaf upset over dwindling audiences, Alfred and Blanche Knopf (the real shocker) swinging on the side; but the more kinky stuff upstages everything. Of course we should be as tolerant and as sex-positive as Bowers. But after Laughton’s sandwich, one has to wonder: how will I watch Witness for the Prosecution now? To paraphrase Henry James on the effect of sex scenes in fiction, the poop and the pee drive everything else out.

Yet Full Service is laborious after a while. Partly this is because the book seldom dramatizes; it simply tells you who did what. The best scene isn’t even about sex: it’s the night in 1979 that Bowers and a friend make Néstor Almendros, the great cinematographer, go to an Oscar ceremony at which Almendros is so sure he hasn’t a chance that Bowers has to shave, shower, dress, and drive him down to the theatre. Of course, Almendros won—for Days of Heaven—and left his Oscar to Bowers after he died of AIDS: poetic justice, since the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences does not recognize Lifetime Achievement in Bowers’ field, though surely the industry depends on it.

The Almendros story is utterly convincing. So why does the reader balk at some of the rest? It’s easy enough to accept Cecil Beaton, Noel Coward, and Tennessee Williams (who wrote a biography of Bowers that Bowers got him to throw away). But the Duke and Duchess of Windsor? A friend obsessed with the Windsors told me he stopped believing the book because Bowers has the duke insisting that he call him “Eddy” and the Duchess “Wally”—two things my historian friend says were never allowed. When I asked my friend if he believed Laughton’s sandwich, he said no. Why? “Too icky.” So there we are. People have various thresholds of credulity—or reasons for believing what they want to. The recent revelation by the intern in the Kennedy White House that JFK had not only deflowered her at nineteen but asked her to blow his aide Dave Powers while he watched and suggested she try poppers at a party in Palm Springs amazed me, whereas a friend said the only thing he found shocking was that the party was at Bing Crosby’s house. To each his own. But if one accepts Clifton Webb, Franklin Pangborn, Roddy McDowell, Noel Coward, Cecil Beaton, Somerset Maugham, Vincent Price, Malcolm Forbes, and the Knopfs, why draw the line at the Windsors?

The issue Full Service raises is one we grapple with in politics—from the White House intern to Dominique Strauss-Kahn to the Arizona sheriff who resigned from the Romney campaign after being outed by an ex-boyfriend whom he’d threatened with deportation if the ex went public, we are awash in sexual shenanigans. Does a person’s sex life tell you something about him or is it utterly irrelevant? I don’t think most people have made up their minds.

Generally, with this sort of memoir, you can finesse the question by simply looking up the star you’re interested in and skipping the rest; but adding to the problem of this genial but strangely empty sexual saga is the fact that it has no index. The book ends instead with the now nearly ninety-year-old bartender driving down from his house in the Hollywood Hills to work a party for a woman in her late seventies who’s still so attractive that he gets an erection thinking about her. One thinks, oddly, of two other sons of Illinois transplanted to California who never lost their positive outlook: Hugh Hefner and Ronald Reagan. There’s something very Midwestern about all of this. It could be a cover of the old Saturday Evening Post (which Bowers delivered as a boy): this gas station on Hollywood Boulevard, where all these ex-Marines were willing to get blown for cash, a Maxfield Parrish painting with dicks.

The only time anyone in Full Service uses the p-word is when Lucille Ball, whose husband Desi Arnaz has been shtupping women supplied by Bowers, sees the latter at a party, slaps him across the face and yells: “You! You stop pimping for my husband, y’hear! … Get out and stay out of my husband’s life!” But how does Bowers react? “The incident didn’t leave me with any anger toward her. She was right.” Some hookers are happy, or at least impervious to insult. Some people do have good looks, big dicks, and no hang-ups when it comes to sex. God bless them.

Andrew Holleran’s latest book is Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited: AIDS and Its Aftermath.