On the Move: A Life

On the Move: A Life

by Oliver Sacks

Alfred A. Knopf. 397 pages, $27.95

IN THE MIDDLE of this richly detailed autobiography, published just four months before his death last August, Oliver Sacks tells a story about himself and a cat. In 1979, he bought a house on City Island, a small seaport community near the Bronx, the first home he owned since moving from England in 1960. One evening he came home to find a stray cat on his porch. He fed the cat, and each evening she awaited his return. They began eating together, the cat on the porch, Sacks inside the house near a window. This “interspecies relationship” charmed him, but at the end of summer he gave the cat away. The story illustrates a pattern: throughout his life, Sacks found it hard to believe that anyone cared for him. When he did find himself in an affectionate relationship, he could not abide it for long and usually put some geographical distance between himself and the other person. Hence, the book’s title. Only in 2008, when the author was 75, did he fall in love—with Billy Hayes, another writer. Their relationship would last for the rest of his life.

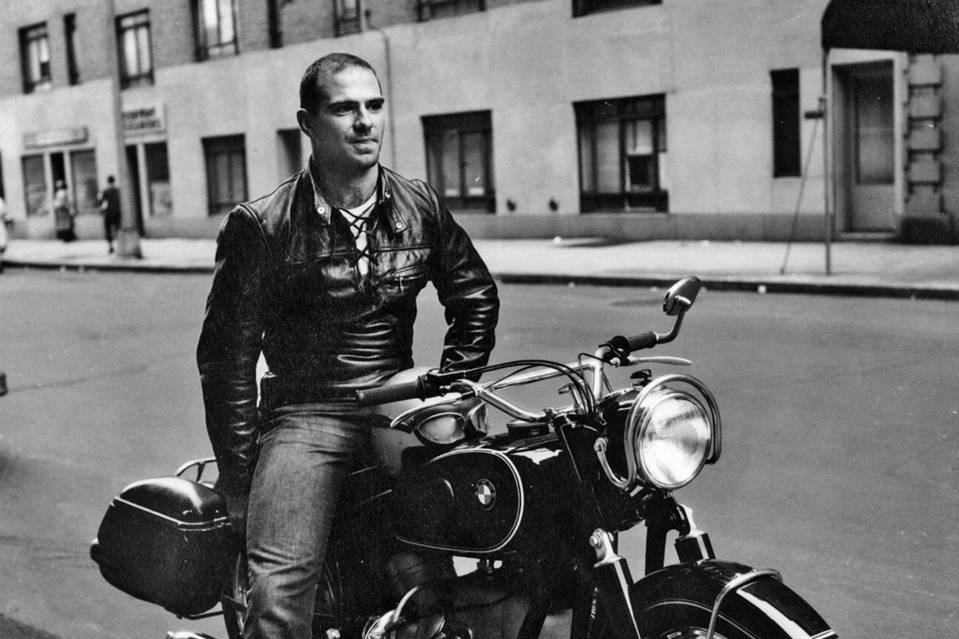

The most startling revelation in On the Move is that Oliver Sacks was gay. He had lived in the public eye since the publication of Awakenings (1973), his book about patients who survived the “sleepy sickness” pandemic of the 1920s with minds and bodies frozen in time and were temporarily awakened by the drug L-dopa. In the following years, as book after book appeared, he presented research at neurological meetings and lectured at universities. Nothing about this burly, bearded man, who appeared shy and reserved, hinted at his sexuality. In fact, when he was eighteen, Sacks told his physician father that he preferred boys; his father shared this with Oliver’s mother, also a physician, who told him she wished he had never been born. Sacks’ relationship with his parents survived, but his decision to leave England was partly fueled by a need to escape the disapproval of his family and Orthodox Jewish community. He tells the story of his very physical, very handsome younger self in the early chapters of On the Move, and they are the most evocative part of the book.

After completing his medical degree in England, Sacks arrived in San Francisco hoping to secure an internship that would qualify him to practice medicine in the U.S. Away from home, he felt free to be sexually active and had a “fling” with a young man who knocked on his door on his first night of staying at the Y. By 1962, he was in Los Angeles, wearing the white coat of a neurology resident at Mount Zion Hospital and a leather jacket on his motorcycle. In his free time, he immersed himself in hyper-masculine activities: motorcycling, weightlifting, mountain climbing, bodysurfing. The book includes a photograph of him setting a California state record in the squat lift.

Sacks was introspective enough to understand that, although weightlifting made his body strong, it did not change his character, which remained “timid, diffident, insecure, submissive.” He acknowledges that his dangerous experimentation with drugs, which continued for a number of years, was an attempt to escape his problems with intimacy. The California years end with a touching story of his close friendship with Mel, a presumably straight young sailor with whom he shared an apartment. The relationship ended when Sacks had an uncontrollable orgasm while giving a naked Mel one of their frequent post-workout massages, an event that ended the innocence of their non-sexual love affair. Writing about this in his ’80s, Sacks realizes how young and confused they both were, and he wonders what became of Mel. Sacks’ sexual activity was sporadic and his romantic relationships brief. In 1973, after a week-long “fling” in England, he was to have no sex for the next 35 years.

Sacks left California, where he felt a “freedom and joy” that he never found on the East Coast, to do a fellowship in New York City, where he lived for the rest of his life. He botched his lab experiments so badly he was invited to leave the program and spend his time seeing patients. This was the beginning of his signal achievement as a physician-writer. A natural storyteller, he was fascinated by his patients. He began to write extensive case histories, more narratives of their lives than clinical notes, and these became the basis for his many books. For the most part, neurologists see patients who have terrible degenerative diseases—ALS, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Tourette Syndrome—for which there are few treatments and no cures. Writing books about the blind, the deaf, and the autistic, among others, he came to see his patients as having different modes of being, and he described how they developed compensatory skills in their struggles to make their way in the world. He was convinced that working with such patients opened him up as a human being and taught him sympathy, something psychoanalysis and dropping acid had failed to do.

Sacks’ stories have moved many readers, but the medical establishment, for which case histories are not verifiable data and patient confidentiality is always an issue, has been skeptical. When the articles he published in medical journals were ignored, he was resentful, but over time he came to believe that his books contributed to “a new vision of the mind” shared by some of his neurology colleagues, the theory that all of us, the neurologically healthy and the challenged, create our consciousness of the world in specific parts of our brains, and each of us does this in a unique way. Observing, as he did throughout his life, how this process takes place in people with neurological disorders gave him a special insight into how the brain works. Oliver Sacks ends his own case history with a chapter called “Home,” in which he describes falling in love with Billy Hayes, and offers the most enthralling description I have read of what it means to live a writer’s life.

Daniel Burr is an assistant dean at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, where he teaches courses in the medical humanities.