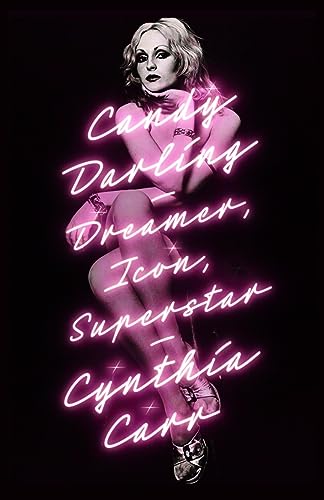

CANDY DARLING

Dreamer, Icon, Superstar

by Cynthia Carr

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

364 pages, $30.

LITTLE JIMMY SLATTERY was too pretty to be a boy. Born James Lawrence Slattery in 1944 to James and Theresa (“Terry”) Slattery, in Queens, New York, Jimmy was preternaturally beautiful even as an infant. When his mother entered him in the Gertz department store beautiful baby contest, he won the title “Most Beautiful Baby Girl.” Throughout his youth, Jimmy suffered the emotional and physical abuse of classmates and others, particularly from his drunken, gambling-addicted father, who was frequently violent with Terry when on one of his drinking binges. Jimmy’s older half-brother (from Terry’s first marriage) Warren later stated: “I cannot remember a time in our childhood of being happy and at peace when my stepfather was around.” As he got older, Jimmy’s estrangement from his father also grew. James Slattery seems to have despised his “pretty” son early on, and the feeling was mutual.

To escape the torments of home and school, Jimmy retreated into a fantasy world populated by the most glamourous movie stars of the 1930s and ‘40s, with a special affinity for Kim Novak (in Picnic) and other “blond bombshells.” As the taunting escalated in high school, now in Massapequa (north of NYC), Jimmy’s sense of isolation deepened. He created excuse after excuse to stay home from school and immersed himself in every B or C movie he found on daytime TV’s Million Dollar Movie. He gravitated toward the girls in the neighborhood, eating lunch with them and joining them for jump rope while the other boys played stickball in the street. He quit school as soon as he turned sixteen and went looking for work and a place to fit in.

After leaving high school, Candy entered the DeVern School of Cosmetology and then began working in DeVern’s salon, where, according to a coworker, Lorraine, Candy was “[a]lways acting … [she would]stop in the middle of doing someone’s hair and do imitations at the drop of a hat.” She began to reinvent herself, dressing and presenting as a female. She assumed the name Candy and, with friends from the salon, started venturing into the City. These friends were quick with advice about make-up, clothes, flirting, and other aspects of behaving “like a woman.” After leaving DeVern’s salon, she remained unemployed and began discreetly turning tricks on her forays into the City.

Candy dreamed of being an even bigger star than her idol Kim Novak. And although she never quite acquired that level of fame, she quickly made a name for herself, acting in friends’ Off-Off-Broadway plays and starring in productions at La Mama E.T.C. She became friends and collaborators with avant-garde theater folk like Charles Ludlam, Jeremiah Newton, and Jackie Curtis. She acted in Glamour, Glory and Gold opposite a young Robert DeNiro. She made films in Munich with German director Werner Schroeter. Due to her uncanny beauty, she was photographed by heavyweights like Francesco Scavullo and Richard Avedon. She was close friends with Lily Tomlin and Jane Wagner, and she met and befriended Christine Jorgensen, the first celebrated gender reassignment surgery patient. Candy was the subject of Lou Reed’s song “Candy Says” on the Velvet Underground’s first album and immortalized in Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side”:

Candy came from out on the Island

In the back room she was everybody’s darling

But she never lost her head

Even when she was giving head

She says, “Hey, babe

Take a walk on the wild side.”

Most importantly, she befriended Andy Warhol at an all-night club called the Tenth of Always and became a regular at his Factory, one of his “superstars” along with Holly Woodlawn and Jackie Curtis. (There’s a famous photo of all three taken by Richard Avedon for the June 1972 issue of Vogue.) He cast her in a short scene in Flesh and gave her a pivotal role in Women in Revolt. Warhol became Candy’s ticket to exclusive art gallery openings, film and theater premieres, and trendy Upper East Side cocktail parties. Warhol seems to have been more fascinated with Candy than with any of his other Superstars. Not only did he give her central roles in two of his best-known films, he took Candy under his wing, introduced her to all the right people, and escorted her to Max’s Kansas City (the place to be seen at the time). He also paid for her dental work (when she was down to just fifteen teeth) and gave her money for rent, clothes, medicine, and whatever she wanted—which was everything.

Perhaps that ambition helps explain why Candy’s story is such a sad one despite the incredible heights she attained. From a very early age, she suffered acute gender dysphoria. Her diary is rife with her laments over being in the “wrong” body. Her “flaw,” as she saw it, was her male genitalia. She longed to be a ravishingly beautiful, stylish, glamourous woman in the mold of 1930s and ‘40s movie stars. She began hormone therapy to make herself more feminine and considered gender reassignment surgery several times, but was held back by a lack of money and a fear of the surgery. She lamented that she had no real friends, that no one understood that she wasn’t a drag queen but, in her mind, a real woman. Many times she wrote in her diary about wanting to commit suicide and wishing to die.

When Candy lay in her bed in the hospital, dying of leukemia, photographer Peter Hujar took a stirring photo of her looking every bit as glamorous as Jean Harlow or Kim Novak in their heyday. On the morning of Candy’s funeral on March 21, 1974, Hugar arrived before other mourners and took a haunting photograph of Candy in her casket, her makeup flawless, her hair coiffed to perfection—a glamor girl to the very end.

Hank Trout, a frequent contributor to these pages, is the former editor of A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine.