THE FIRST TIME a stranger placed his hand on Jack Worby’s thigh, Jack was not entirely sure what to do. He was seventeen, an orphan who had been shuttled among various foster homes and reform schools, but now he was on his own and on the road in Buffalo, New York, confronted with a situation he had never faced before. The stranger seemed nice enough, gentle and reassuring, Worby later wrote, and “when he kept endearing me with his words and caresses I began to get a queer sensation which I could not for all the world of me account for. It was a sort of soothing thrilling feeling which seemed to urge itself on as soon as he touched me. It seemed as if I didn’t want him to take his hand off my thigh and when at last he did take it off I had a feeling of utter loneliness. I had never experienced anything like this before and the fact that I was with a man made it all the more difficult to explain.”

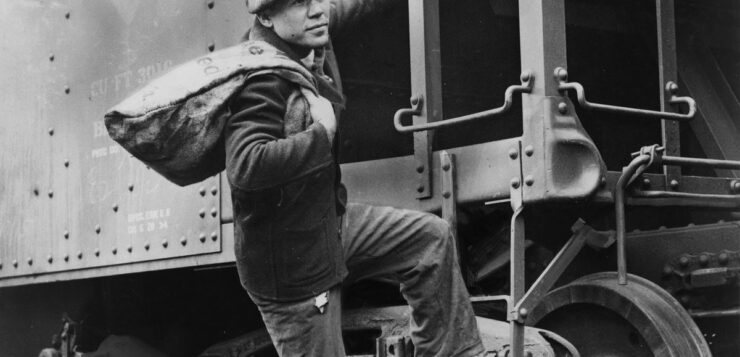

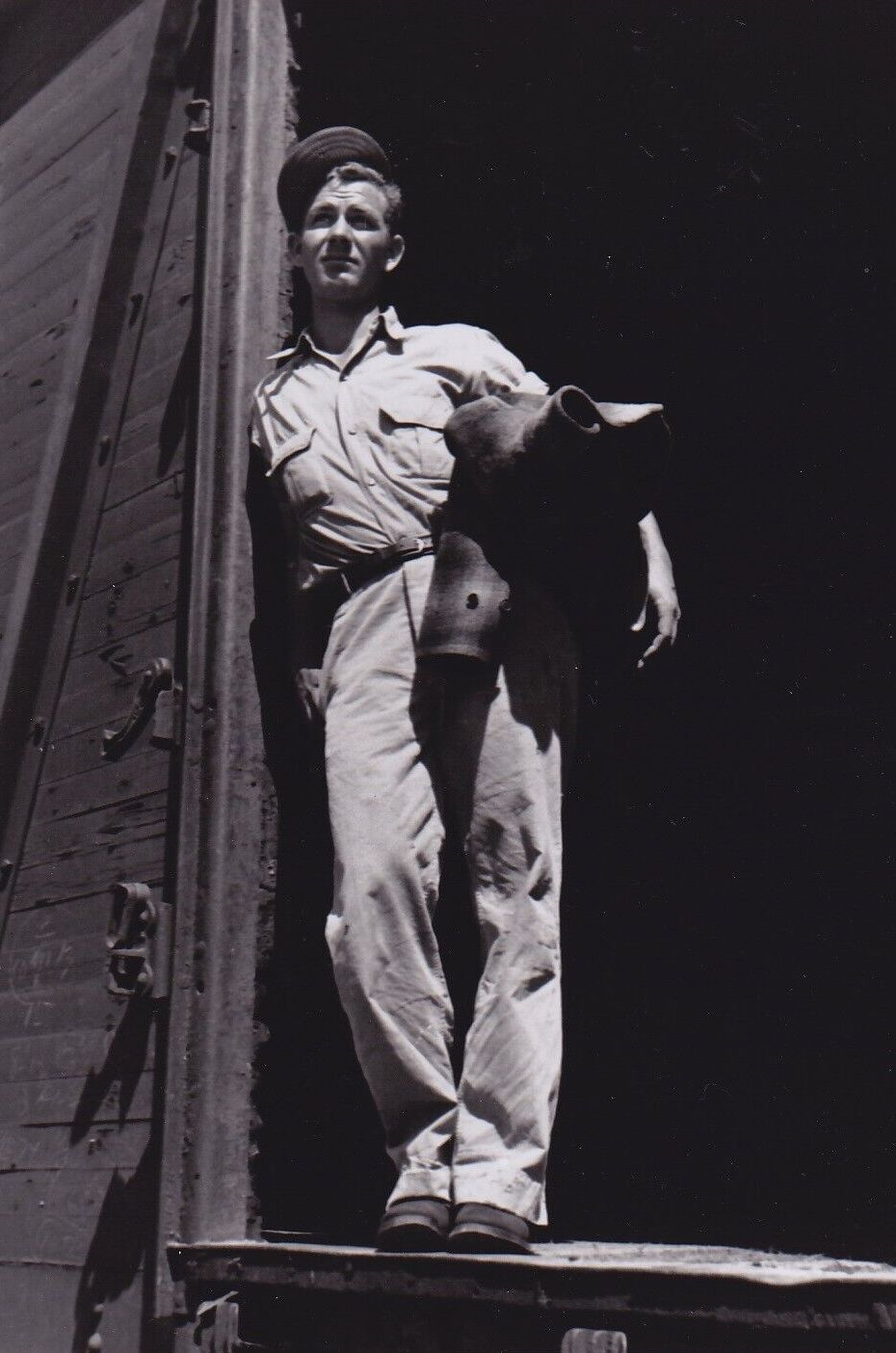

Jack Worby was one of the hundreds of thousands of young men who took to the roads and rails of America in the decades between the end of the Civil War and the onset of the Great Depression of the 1930s. They called themselves tramps or hoboes or ’boes. Poets and sociologists called them vagabonds. Cops called them vagrants. The Industrial Workers of the World called them a successful anarcho-syndicalist society. Many people called them bums. Their numbers would soar during economic downturns like the Wall Street crash of 1873 or the Panic of 1893, but there was always a core group who were on the road, not because they could not find a job, but because they had been restless and unhappy in the places they came from. Novelist Jack London wrote of his reasons: “I became a tramp—well, because of the life that was in me, of the wanderlust in my blood that would not let me rest. … I went on ‘The Road’ because I couldn’t keep away from it; because I hadn’t the price of the railroad fare in my jeans; because I was so made that I couldn’t work all my life on ‘one same shift’; because—well, just because it was easier to than not to.”

Jack Worby was one of the hundreds of thousands of young men who took to the roads and rails of America in the decades between the end of the Civil War and the onset of the Great Depression of the 1930s. They called themselves tramps or hoboes or ’boes. Poets and sociologists called them vagabonds. Cops called them vagrants. The Industrial Workers of the World called them a successful anarcho-syndicalist society. Many people called them bums. Their numbers would soar during economic downturns like the Wall Street crash of 1873 or the Panic of 1893, but there was always a core group who were on the road, not because they could not find a job, but because they had been restless and unhappy in the places they came from. Novelist Jack London wrote of his reasons: “I became a tramp—well, because of the life that was in me, of the wanderlust in my blood that would not let me rest. … I went on ‘The Road’ because I couldn’t keep away from it; because I hadn’t the price of the railroad fare in my jeans; because I was so made that I couldn’t work all my life on ‘one same shift’; because—well, just because it was easier to than not to.”

Most Americans were aware that men of Jack London’s ilk were adrift across the country, men who had stepped away from the obligations of steady employment in order to travel by hitchhiking or by leaping onto moving freight trains. To some observers of a more romantic bent, these men were kin to the bohemian artists and writers in Parisian garrets or in the basement apartments of Greenwich Village—hungry by choice, unemployed by design, bravely marching to a different drummer. The special community that those tramps created became known by the portmanteau word “Hobohemia,” and while life on the roads and rails was often cold and rough, tramps during this early period could depend on a surprisingly sympathetic network of community support during their wandering. Police stations often allowed tramps to sleep overnight in unlocked cells or even in hallways, and a knock at the back door of many homes at mealtime could secure a “poke-out” (a meal wrapped in an old cloth or newspaper) or even a “set-down” (an invitation to eat at the family table).

From its inception, Hobohemia was overwhelmingly male and white. For all the pæans to the joys of the open road, “The Road” for many Americans was neither joyful nor open. Women traveling alone were assumed to be of easy virtue and were subject to harassment. There were female hoboes, but their number was so small that when Bertha Thompson’s Sister of the Road: The Autobiography of Boxcar Bertha was published in 1937, it shocked and fascinated the nation. Not until years later did sociologist Dr. Ben Reitman admit that he was “Bertha Thompson,” and that the book was a work of fiction based on the lives of the few hobo women he had been able to interview. The true number of women on The Road is impossible to calculate because they were intentionally excluded from most surveys (their number was assumed to be statistically insignificant), and because some women traveled undetected, disguised as men for their own safety.

The Road was home to a relatively small number of men of color, primarily Blacks fleeing the restrictions of the Jim Crow South, or, especially in the Southwest, Latinos. In the hobo “jungles” (outdoor gathering spots at the edge of town), all races were usually welcome to gather around the campfire and share in communal meals—so much so that the jungle was referred to as “the melting pot of trampdom”—but the police were not likewise equitable in their treatment of vagrants, and a person of color who knocked on a back door at dinner time was likely to be turned away. The informal supporting network that made hobo life possible was simply not there for women or men of color, so only a brave few ventured out. The Great Depression radically changed The Road. A more diverse population—in ethnicity, age, and gender—hit the rails, while community soup kitchens and New Deal work programs replaced the private charity of the back door “poke-out,” aided by the efforts of “Sally Ann” (the Salvation Army) and “Willy” (Goodwill). But beginning in the 1870s and until the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the faces that grinned from “side-door Pullmans” as freight train boxcars rattled past were overwhelmingly young, white, and male. And horny.

The promise—or threat—of sex hung over The Road like musk in rutting season. When 21-year-old Len De Caux climbed into a boxcar in 1921, he was greeted by a man who initiated the conversation by offering to pimp for him: “You’ll look okay … when you’re all dolled up. There’s rich guys goes for a clean-appearin’ punk.” De Caux had no desire to be anyone’s punk, but he was frequently too exhausted to fend off exploring fingers. “Once I awoke, after a crawly nightmare, to find my fly-buttons undone and my private parts exposed to public view.” Homosexual activity was usually not so stealthy, though—nor so one-sided. “I took a crack at him, and he took a crack at me,” one hobo explained, stressing the mutuality of a sexual encounter. In hobo slang the practice was known as “going 50-50.”

The first ethnographic studies of hobo life in America were published in 1893, first as individual journal articles and then collected as a book, by Josiah Flynt (penname of Josiah Flynt Willard). The book Tramping with Tramps was based on nearly a decade of association with these men, including an eight-month stint of living on The Road himself, during which Flynt became one of the earliest “participant observers,” as sociologists would come to call them. Flynt’s reports overturned one of the most enduring myths of the hobo: that he was a solitary wanderer. Instead he found that men on The Road tended to gather into small supportive families. The hobo has “the desire to feel that although he is forbidden the privileges and rights of a polite society, he can nevertheless identify himself with just as definite and exclusive a community as the one he has been turned out of.” Tramps found companionship in what Flynt called “outcast’s clubs” of like-minded men, and although he supplied brief sketches of some of the shared interests that might draw men together, Flynt felt that one type of tramp association was simply “too vile for description.” Nevertheless, he later described in some detail (based, he informed the reader, on “what I have personally observed”) homosexual practices that were supposedly too vile for him to describe: “usually what they call ‘leg work’ (intercrural), but sometimes immissio penis in anum.”

So groundbreaking was Flynt’s exploration of homosexuality among tramps that he was invited to contribute an appendix to Havelock Ellis’ Sexual Inversion (1897). “Every hobo in the United States,” Flynt wrote, “knows what ‘unnatural intercourse’ means, talking about it freely, and, according to my finding, every tenth man practices it, and defends his conduct. Boys are the victims of this passion.” Avoiding any discussion of sex between two consenting adults—the hobo’s “going 50-50”—Flynt instead wrote at length about men who had sex with boys. He was particularly dismayed by the number of young people who seemed to admire tramps, and to be willing participants in sexual pairings. “The general impression made on me by the sexually perverted men I have met in vagabondage is that they are abnormally masculine. In their intercourse with boys they always take the active part. The boys have in some cases seemed to me uncommonly feminine, but not as a rule. In the main they are very much like other lads, and I am unable to say whether their liking for the inverted relationship is inborn or acquired. That it is, however, a genuine liking, in altogether too many instances, I do not in the least doubt.”

The older participant in these relationships was known as the “jocker” or “wolf,” and the younger was known as the “prushun” or “punk.” Flynt condemned these liaisons as sordid and exploitative, but also reluctantly agreed that in many cases the boys were eager partipants. “Some of them have told me that they get as much pleasure out of the affair as the jocker does. … Those who have passed the age of puberty [about sixteen in the late 19th century]seem to be satisfied in pretty much the same way that the men are.” While our response to reports of sex between men and boys on The Road is necessarily complicated by current understandings of agency and consent, in this period a very different set of assumptions was firmly in place. The concept of “teenager”—a distinct transitional stage between child and adult—did not develop until the 20th century. Before that, working-class boys (and girls) were expected to take their place in factories or on farms as soon as their formal education ended, and few attended school beyond the eighth grade. Moreover, at the end of the 19th century, the legal age of consent in some states was as young as nine years old. Clearly, it was a different world.

In 1947, America’s radio airwaves were filled with folksinger Burl Ives’ recording of “The Big Rock Candy Mountain,” a song about a hobo paradise of lemonade springs and soda-water fountains, with a lake of stew (and of ginger ale too), where the cops have wooden legs, the bulldogs have rubber teeth, and jails are made only of tin. Like many popular folks songs, it is a sanitized version of a ballad that originally had rather dark overtones. “The Big Rock Candy Mountains” was first recorded by Harry “Haywire Mac” McClintock in 1928, though he claimed to have written it in 1895 during his hobo days in Louisiana. The lyrics originally referred to the tall tales that jockers would tell young boys in hopes of luring them to a life on The Road. “[T]he ambition of every real hobo,” McClintock explained in a recorded interview, “was to snare some kid to do his beggin’ for him, among other things. They used to tell the kid fairy stories about the lemonade springs and the Big Rock Candy Mountains and so forth.” But before recording his song, McClintock felt he needed to censor the lyrics to make them palatable for the general public. “I wanted to clean this song up—it wasn’t a parlor song originally.” McClintock referred to his extremely popular 1928 recording as “the clean version.”

In 1947, America’s radio airwaves were filled with folksinger Burl Ives’ recording of “The Big Rock Candy Mountain,” a song about a hobo paradise of lemonade springs and soda-water fountains, with a lake of stew (and of ginger ale too), where the cops have wooden legs, the bulldogs have rubber teeth, and jails are made only of tin. Like many popular folks songs, it is a sanitized version of a ballad that originally had rather dark overtones. “The Big Rock Candy Mountains” was first recorded by Harry “Haywire Mac” McClintock in 1928, though he claimed to have written it in 1895 during his hobo days in Louisiana. The lyrics originally referred to the tall tales that jockers would tell young boys in hopes of luring them to a life on The Road. “[T]he ambition of every real hobo,” McClintock explained in a recorded interview, “was to snare some kid to do his beggin’ for him, among other things. They used to tell the kid fairy stories about the lemonade springs and the Big Rock Candy Mountains and so forth.” But before recording his song, McClintock felt he needed to censor the lyrics to make them palatable for the general public. “I wanted to clean this song up—it wasn’t a parlor song originally.” McClintock referred to his extremely popular 1928 recording as “the clean version.”

Given how the song has been revised and expanded, censored and appropriated by various singers over the years, there is now no way to reconstruct with certainty McClintock’s unrecorded, unclean version, but a variety of surviving lyrics provide a good idea of what may have been sung around the campfires in the hobo jungles of 1895:

One sunny day in the month of May

A burly bum came hikin’

Down a shady lane through the sugar cane

He was lookin’ for his likin’.

Oh, a farmer’s son, he was on the run

To the hayfield he was boundin’.

Said the bum to the son, “Why don’t you come

To the Big Rock Candy Mountains?’ …

So the very next day they hiked away,

The mileposts they were countin’

But they never arrived at the lemonade tide

In the Big Rock Candy Mountains.

The punk rolled up his big blue eyes,

And he said to the jocker, “Sandy,

I’ve hiked and hiked and counted ties,

But I ain’t seen no candy.

I’ll be God damned if I hike any more

To be buggered sore like a hobo’s whore

In the Big Rock Candy Mountains.”

Haywire Mac’s blue-eyed farmer’s son would not have been alone on The Road after spurning his jocker. Boys, too, traveled in “outcast’s clubs,” a band of juveniles that was known as a “push.” Members of a push might range in age from about ten to sixteen, but by the time a boy reached his mid-teens he would begin to age out, feeling it was time to leave the push and join a group of men. The boy gangs varied from a loose gathering of pals traveling together seeking adventure to “a highly organized machine that has secret codes, pass words, signals, and prearranged plans of action.” Jack London had a healthy respect for boys traveling in a push. “Road-kids are nice little chaps,” he wrote, “when you get them alone and they are telling you ‘how it happened’; but take my word for it, watch out for them when they run in pack. Then they are wolves, and like wolves they are capable of dragging down the strongest man.”

While young boys were traveling in packs, college students were being offered a different form of education. In 1915, Professor Robert Park of the University of Chicago suggested a new direction for their Department of Sociology. He proposed “a laboratory or clinic in which human nature and social processes may be most conveniently and profitably studied.” Those social processes would include alcoholism, drug addiction, homelessness, prostitution and homosexuality—topics until then handled primarily as moral or legal issues, and largely ignored by academia. The new curriculum was intended to immerse his students in the lives of society’s marginalized communities, with the goal of finding solutions to the problems those communities encountered.

One of the most successful graduates of the Chicago program was Nels Anderson, whose dissertation on hoboes was rushed into print by the Department as an example to the program’s funders of what might be accomplished by a close analysis of often-neglected social problems. Anderson was a former tramp himself, and so was able to quickly gain the confidence of the men he wanted to interview. He confirmed what Josiah Flynt had written decades earlier about the sex lives of hoboes. “All studies indicate that homosexual practices among homeless men are widespread. They are especially prevalent among men on the road among whom there is a tendency to idealize and justify the practice.” Anderson’s field notes were eventually deposited with the Gray Special Collections Research Center at the University of Chicago, where they now provide an intimate view of life on The Road as it was a century ago.

One interview is particularly frank and poignant. In Anderson’s field notes, the youth is identified only as “Document 122 / Boy Tramp.” Let’s call him “Sam.” Sam was eighteen and from Dayton, Ohio, but, when Anderson began to interview him, he was temporarily living on what hoboes referred to as the “Main Stem,” the skid row district centered on West Madison Street in Chicago. Anderson confessed in his field notes that he had represented himself as a news reporter researching a story about the neighborhood, and sensed that Sam felt “honored” that his life was deemed worthy of newspaper coverage. The two met for several interviews. “I suspected that he was homosexual,” Anderson wrote in his field notes, “so I asked him one day if he was. I told him that it did not make any difference to me what practices he indulged in, but I wanted to learn something about it.” Sam at first denied being homosexual, but Anderson continued pressing during subsequent interviews. “I asked him again if he himself did not belong to the ‘sisterhood’ sometimes. He admitted that he did, and he volunteered his story.”

Sam explained that he had never heard of “such practices” back in Ohio, but when he was sixteen (in 1920), he went on The Road, to Kansas, to work in the wheat harvest. There he met a tramp who expressed an interest in him, even sharing food the man had obtained by begging. They spent most of the day together, but then Sam hopped an outbound train. He was surprised when he ran into the man again in a town about fifty miles away. This time the two stayed together, and in the evening they shared a strawstack on the outskirts of town. The man wanted to have sex, and though Sam at first declined, he eventually agreed. He stayed with the man for several days, “and each night they would retire to some strawstack or other obscure place, where the man would hug and kiss him. He allowed the fellow to masturbate him each evening.”

Eventually Sam began to feel “afraid and ashamed,” and caught a train out of town. For a month he avoided sexual contact with other tramps, until he was approached by a man who was sleeping with him in a boxcar, a man he found irresistibly attractive. “This man also played with his penus [sic]and masturbated him while performing the rectal coitus. He did not care so much for the female role, but he permitted it as part of the process of getting satisfaction.” Sam stayed two nights with the man, but then again became disgusted with himself, and swore he would avoid all sexual contact with men in the future. His resolve lasted for only “a week or two.”

At the end of the summer, Sam returned to Ohio, but by the following spring he began to feel “uneasy.” There was no sex to be found in Dayton, and he was eager to return to places where he could find it. He headed for the farms and fields of Nebraska and the Dakotas, where he was once again approached. “This time he yielded with less coaxing than before. He began to get a certain pleasure out of the practice, and even put himself in the way of men who seemed to be interested.” At the time of the interviews with Nels Anderson, Sam was living in Chicago, but he was eager to jump a train to join the migrant laborers in the Midwest. Anderson described Sam as “an intelligent, handsome lad of good build, and the very type that would attract the wolf,” and he was surprised that such a normal-appearing young man felt no shame at all about being part of the “sisterhood.” Sam had found his family of choice, and appeared to be happy about it. Anderson’s field notes on “Boy Tramp” conclude by recording Sam’s personal philosophy. “He has boiled the problem of getting along, down to this: ‘A man has got to live and enjoy himself,’ and that would mean to enjoy himself at the things he enjoys, as long as he may.”

While many observers wrote about tramps engaging in homosexual activities while on The Road, Nels Anderson came closest to reversing the issue by discussing why “perverts” might choose to become tramps. “The greatest danger the pervert faces is that of being ostracized,” Anderson noted. “So long as one is in the tramp class this danger does not worry him.” The conditions were perfect for a man fleeing possible scandal in his hometown. Tramps usually traveled anonymously, adopting a “monica” (moniker) by which they were known by friends and strangers alike. (Jack London’s was at first “’Frisco Kid” and then “Sailor Jack.”) Every tramp also prepared a standard “line” about himself, a brief biography designed to give out the least amount of information about his past. Anyone who asked too many questions—or who shared too much information about himself—aroused suspicion.

Any homosexual who took to The Road would find himself in a community that included “abnormally masculine” men who engaged in sex with one another, men who preferred to reveal as little as possible about their own background, and who were never in one place long enough to become known except by a colorful moniker. At a time in American history when gay men had few options but to remain hidden, the open road provided the perfect closet.

References

Anderson, Nels. The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man. University of Chicago Press, 1923.

DePastino, Todd. Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America. University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Flynt, Josiah. Tramping with Tramps: Studies and Sketches of Vagabond Life. Century Co., 1899.

London, Jack. The Road. Macmillan, 1907.

William Benemann is the author of Men in Eden: William Drummond Stewart and Same-Sex Desire in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade and Unruly Desires: American Sailors and Homosexualities in the Age of Sail.