FOLLOWING RAINBOWS

FOLLOWING RAINBOWS

The Fast Times and Fleeting Fames in Gay Bangkok’s Boy Soi

by Mike Maloney

Independently published

150 pages, $9.99

CHOOSING TO BE GAY

CHOOSING TO BE GAY

One Man’s Improbable Path from Living Straight to Loving Gay

by Mike Maloney

Kindle/Direct Publishing

150 pages, $16.

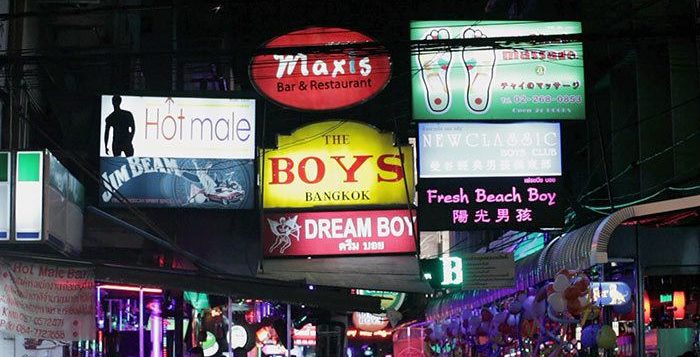

MOST GAY PEOPLE, when they discover the gay world, do so in a place that seems to them, at least for a while, the fulfillment of all their dreams. For many, before the Internet, it was at the bars; for others, the baths, the beach, the cruising block, and so on. For Mike Maloney it was on a side street off one of the main avenues in Bangkok, Thailand, called Soi Twilight or, as he nicknamed it, Boy Soi.

These places generally fulfill our dreams for only a limited period, or at least we don’t go to them every night of our lives as we may when we first discover their existence. We love the bars, for instance, but eventually tire of them as a steady diet. What’s extraordinary about Maloney’s memoir of his years visiting Bangkok, Following Rainbows, is how long his enchantment lasts. In his book, the time frame is hazy, though at one point he refers to fifteen years of attendance at the boy bars that made Bangkok a magnet for sex tourism.

In Japan from the 17th to the mid-19th century, the brothels, prostitutes, geisha, sumo wrestlers, and kabuki actors were located in a moated neighborhood of Edo (Tokyo) that was called the “Floating World”—“floating” in the sense of transient and fleeting. Maloney’s take on the boy bars of Bangkok is based on the very same theme: the fleeting nature of youth and beauty, not to mention popular tastes that eventually move the whole scene to another block. The reader is never sure how long Soi Twilight lasted; nor does Maloney deal with the effect AIDS had on it all (save in one of the individual boy’s stories at the end of the book), though I’m told by a friend that the Covid pandemic has brought this world to a halt.

Concerning everything else that he discusses, Maloney is very specific. What’s so engrossing about Following Rainbows, besides the natural, frank voice of the author, is its attention to detail. When Maloney discovered the Boy Soi, he had been working as a businessman in Southeast Asia for years, a married man with a wife and family in Texas who came out, as he puts it, “later in life”—as opposed to “late in life”—with the consciousness of his own fleeting chance of finding a gay boyfriend before he was too old. One calculates that he was in his fifties when he met Joe, a 22-year-old Thai, with whom he was in love for two years. Joe introduced him to the Thai version of the Floating World by taking him first to a ping-pong bar—a bar featuring nearly nude women who pole-dance on the ground floor and shoot ping-pong balls out of their vaginas on the second. (In the gay version a young man shoots darts out of his asshole that puncture a balloon held by another man.)

Most of the customers in these places are older and foreign, coming from not only Europe and the U.S., but also from Japan, China, Korea, and Australia. The latter countries also supply some of the performers—Koreans, Cambodians, and Vietnamese—but it’s the Thai boy, the Thai cheekbones, and above all the Thai smile that transfix Maloney. After realizing that his relationship with Joe is not going to work, he finds another Thai beauty in one of the bars, who introduces him to several friends from the same milieu whose stories round out the end of the book.

The boys in the bars, Maloney states at the outset, share certain characteristics: they are from poor places in the country, they honor the Asian ideal of supporting the family (to whom they send back part of their earnings), and they are young, slender, and handsome—“classically sweet, classically effeminate, and classically twink.” Some (like Joe) are straight, and some (like his new boyfriend Bon) are gay. Maloney prizes the Esan Thai, a strain of the Thai populace from northeast Thailand, above those with a Chinese background. He also prizes a trait that Thai culture rates highly: kindness. The only boy Maloney even considers sleeping with, once he has found Bon, is not the best-looking of the bunch, but the sweetest. And that boy turns him down, because among the bar boys, there is a rule: You do not cruise your friend’s boyfriend.

At the same time, the two traits that enable these boys to survive and flourish on the Boy Soi, Maloney concludes, are cunning and narcissism. The goal is to be popular. The number of a bar boy’s “comings and goings” with different customers (to their hotel room) over the course of an evening is the measure of their success. When asked about a mutual friend named Film, one of Bon’s chums says: “Film told us all the wonderful things Film has been doing: what country he has been to with what customer or new boyfriend; what latest Apple device or gold necklace someone has just bought for him; and most important of all, what next nose, lip, eyelid, or wrinkle procedure Film is planning.”

These measures are meant to forestall the fact that “bodies gradually grew thicker. Faces took on some fine lines. Wild-ass energy began to wane. Those inescapable effects of The Buddha’s Impermanence Principle.” The best thing of all is “having a place to go to—a place where they could still ‘be somebody’—when their rainbow beauty began fading away.” Before that, to forestall the loss of their looks, “among the two or three most popular past-times are … adding another tattoo; injecting another sixteen units of Botox; and undergoing a third or fourth nose job. Sometimes all three of these nearly at once.”

Maloney distinguishes between “twinks”—boys with slender natural bodies—and “twunks,” boys who, though still slender, obviously go to the gym. Then there are ladyboys, whom we would call trans, and straight guys, whose tattoos tend to be bigger and who, if they are Korean, tend to be more domineering. But whatever the subgroup, the business of all the bars is the same: boys. It’s never quite explained how the system works. Apparently the boys pay the bar a fee for being allowed to work there. The best outcome is the sugar daddy, the Japanese or Korean or Australian man who takes the boy out of the bars and sets him up abroad, giving him money to start a shop or helping him become an Australian citizen—which sometimes works out and sometimes doesn’t.

Maloney is so entranced by the Boy Soi that he explains the various ways the bars cheat their customers—substituting half-filled bottles for the one you ordered when you’re too drunk to notice, introducing toasts that require you share your booze with everyone at your table—things that normally would induce resentment, but not in Maloney, who distinguishes between cheating that’s just “the way things are” and the unfriendly “screw you” kind. The former he is willing to overlook to be where he wants to be: ringside.

At one point he mentions in passing that he and Bon have started going to a certain bar because they’ve grown bored with the other bars’ shows, but that is the sole instance when the specter of ennui raises its head. Otherwise, Maloney finds the Boy Soi endlessly entertaining, endlessly interesting. And why not? He and Bon are liked by the staff—they always order a bottle of Johnny Walker, they tip well, they share—and at the end Maloney becomes good friends with several of Bon’s former coworkers. Their stories are the reader’s reward, these accounts of individuals who move to Korea with boyfriends, or return to the family farm, or grow beefy after they reach the dreaded age of thirty. Throughout the book, Maloney hews closely to the metaphor he has chosen for his title: the boys, like everything in the Floating World, are like rainbows that appear so beautifully but then quickly vanish, subject to the Buddhist Principle of Impermanence.

You may, after reading Following Rainbows, want to take a video walking tour of these streets on YouTube. The impression is that of Times Square elongated on narrow alleys that remind you of how grimy and sordid the sex trade scene can be. You may even view the scene in terms of exploitation and economic inequality. Still, in Maloney’s remarkably nonjudgmental telling, it achieves an interest and finally a poignancy that are quite moving. Perhaps its very transience is what drew Maloney to the Boy Soi all those years ago, or the feeling that we have when we first come out and find a place that seems the answer to all our desires. Even when it comes time to end his book, he cannot quite let go: Following Rainbows ends not with just an epilogue, but an afterword, and finally a postscript—as if there were still more to tell.

There is more to tell, but you have to read his first book to get that story. In Choosing to Be Gay (2020), Maloney describes how he came out in his fifties while married to a woman with whom he has two sons. It’s a harrowing journey that includes lying to a priest, seeing a therapist, and finally coming out to his wife and sons, not to mention his doomed love for Joe and his finally finding a partner in Bon. It’s about what he and thousands of other older gay expatriates have found in Thailand. Maloney is not just taken with Esan Thais but with Thailand itself, which, as the world’s most populous Buddhist country, adheres to the principles of Buddhism, above all the importance of kindness. Indeed, what allows Maloney entrance into Thai culture is really his own kindness, and the financial generosity that fuels his first foray into gay life with Joe. It’s about Maloney’s immersion not only in gay culture but in Thai culture, especially when Bon takes him to his family home for the ceremony in which Bon becomes a Buddhist monk (something which does not obviate a return to normal life). Choosing to Be Gay is as serious as Following Rainbows is light, as if, now that the hard work of coming out is over, he can now simply enjoy himself.

But having read both books, I still don’t know how Maloney manages the dichotomy: twelve weeks of the year in Bangkok and the rest in Austin. So what is his life in Texas like? What does Bon do the nine months when Maloney is not in Bangkok, or does Bon go to Texas too? In Following Rainbows (which can be read merely as a delightful travelogue), these questions are not answered. One never quite knows why he and Bon are happy to sit in the bars night after night. Is this the only thing they have in common or simply their favorite pastime? Following Rainbows is too light to go into that. But if the pandemic has brought much of this scene to a halt, that may be another reason Maloney added a sequel to Choosing to Be Gay: because, like the Floating World, Boy Soi proved all too fleeting. It’s back to the Buddhist Principle of Impermanence. The way to Enlightenment begins with the boy bars of Bangkok.

Andrew Holleran is the author of the novels Dancer from the Dance, Nights in Aruba, The Beauty of Men, and Grief.