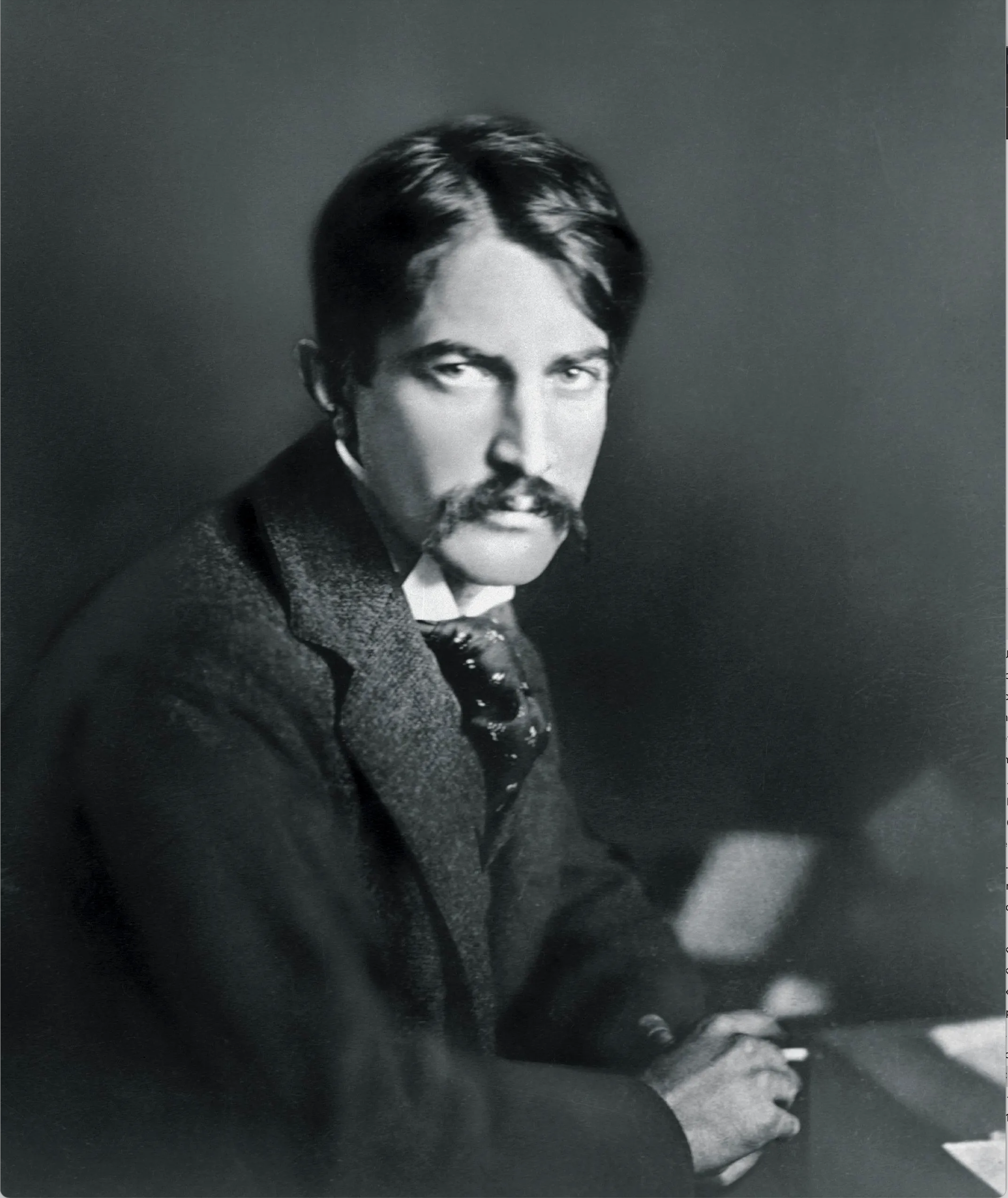

LATE on a brisk New York evening in 1894 (or so the story goes), Stephen Crane (1871–1900), not yet famous for The Red Badge of Courage, was crossing Union Square together with the arts critic James Gibbons Huneker. Huneker had been to the theater and was in dapper evening dress, while Crane was in his usual rumpled and patched bohemian garb. The two friends had met up by chance in the street and were now on their way to a late supper at the Everett House hotel, although Huneker had imbibed heavily during the play’s intermission and confessed to being already somewhat in his cups. In the square, they were approached by an emaciated young man who smiled at them provocatively. “I was drunk enough to give him a quarter,” Huneker later wrote. “He followed along and I saw that he was really soliciting.” Union Square was one of the main sites for homosexual cruising in New York City, but Crane (according to Huneker) was too naïve to understand that the youth was hoping to barter a hot meal for a blow job.

“We got to the Everett House and we could see that the kid was painted. He was very handsome—looked like a Rossetti angel—big violet eyes—probably full of belladonna.” Crane, who liked to steep himself in the lives of the downtrodden to assure the authenticity of his prose, saw in this frail painted angel a portal into a world about which he knew very little. He invited the gaunt young man to join them for dinner at the hotel, where he could pump him for information about New York’s homosexual underworld.

Edmund White, in his novel Hotel de Dream, imagines the scene in the Everett House dining room from Crane’s point of view. “There was a table free but the headwaiter glanced at the manager—but couldn’t stop us. We headed right for the table, which was near Siberia, close to the swinging kitchen doors. I placed my frail burden in a chair and, just to bluff my way out of being intimidated I snapped my fingers and ordered some hot soup and a cup of tea. The headwaiter played with his huge menus like a fan dancer before he finally acquiesced and extended them to us.”

Later, again according to Huneker, Crane began a novel to be titled “Flowers of Asphalt,” about a country boy who comes to New York to pursue his dream, only to end as a street hustler dragged down by drugs and syphilis. Crane read the opening pages of the manuscript to his mentor, the writer Hamlin Garland, who was so disgusted by what he was hearing that he insisted that the reading of this sordid tale cease immediately, and the existing pages be consigned to the flames.

That, at least, is one version of the story. Its accuracy has been questioned, as it relies solely on a one-page reminiscence by James Gibbons Huneker himself. Yet the story has legs because it clearly could be true, given what is known about Stephen Crane’s life. Crane was the son and grandson of Methodist ministers, and he was reared in a home where the line between the righteous and the damned was clearly delineated. But from at least his college years at Syracuse University, Crane made it clear that his sympathies lay with the damned.

His first novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, displays an uncanny ability to climb inside the head of an adolescent girl who has known only violence and degradation, but who has somehow managed to guard a small candle flame of belief in a romantic future—until that flame, too, is snuffed out. In a later novel, George’s Mother, Crane slips the reader into the cigar-stench of Bowery saloons and all-male house parties where rough men bond and boast and fight, until they collapse in a boozy heap on the bedroom floor. To assure the authenticity of his stories, Crane haunted the night courts of Syracuse and the seven-cent flophouses of the Lower East Side, talking to sex workers and opium addicts about their lives, sitting for hours in the dark shadows of dive bars, nursing a single drink while he watched and listened, recording everything like a human Kinetograph camera.

Yet Crane’s published novels and short stories never touch on New York’s extensive and varied population of homosexuals. This reticence is not surprising, given how Maggie: A Girl of the Streets was received. Crane could find no publisher willing to take on the manuscript, so he sold his part of a family inheritance to his brother in order to self-publish. Even then, the printer was so repulsed by the subject matter that he refused to allow his company’s name to appear on the book, and—wavering in his own resolve to publish and be damned—Crane decided at the last minute to adopt the pseudonym “Johnston Smith” for the title page. When he attempted to peddle the book, he encountered further discouragement. Brentano’s was one of the few bookstores willing to carry the novel. They took a dozen copies—and eventually returned ten.

Shivering in his garret room, sometimes eating only one meal a day, Crane found it cold comfort that his first novel was at last in print as he stared at the stacks of unsold copies. In a bohemian scene straight out of Puccini, he took to ripping out pages and feeding them to the fire in order to keep warm. Crane was poor and hungry. He could not afford to write something that would not sell, and if a novel about a female prostitute caused booksellers to blanch and slam their doors, what point would there be in writing a novel about a homosexual? The lesson was driven home when he sent a copy of Maggie to novelist John D. Barry, who was unsettled by the subject matter and strongly urged him to keep in mind literature’s effect upon the reader: “as soon as that effect approaches the morbid, the unhealthful, the art becomes diseased. It is the taint in the peach.”

To most 19th-century readers, homosexuals were clearly tainted fruit, but for Crane they were still well within the compass of a writer fascinated by the outcasts of American society and eager to tell their stories. Yet, in his novels, short stories, and poetry, in the many newspaper columns he wrote to put food on the table, in the 1,379 pages of the Library of America edition of his selected works, there is only one work that appears to concern itself with men sexually attracted to other men.

In 1895, the Bacheller newspaper syndicate sent Crane on a trip west and south, all the way to Mexico, with an assignment to send back color commentary along the way. From Hot Springs, Arkansas, he dispatched a column about the men who gather at the bathhouses of the popular thermal resort. In an article titled “Seen at Hot Springs,” Crane opens with an observation he may have intended to be blandly generic, but given the cryptic story that he then proceeds to tell, he may instead have been hinting that men who seek men sometimes seek them at the baths. “[N]o man need feel strange here,” he begins his essay. “He may assure himself that there are men of his kind present. If, however, he is mistaken and there are no men of his kind in Hot Springs, he can conclude that he is a natural phenomenon and doomed to the curiosity of all peoples.”

Crane then reports a small drama involving three strangers who encountered one another in the bar of a bathhouse, a drama observed by someone who plays no role in the story: “At the end of the bar was lounging a man with no drink in front of him.” This no doubt is Crane himself, as always listening closely, taking no part, but mentally recording it all. The three participants in the drama are unnamed, except by a descriptive phrase. One, referred to only as “the traveler for the hat firm in Ogallala, Neb.,” begins to chat up “the youthful stranger with the blonde and innocent hair.” They are observed by a third man, who is leaning against the bar, ruffling his whiskers thoughtfully. The traveling salesman suggests to the blond youth that they share a glass of mineral water and then go to a concert together. Before the youth can respond, the bearded man intervenes, challenging the salesman to a game of dice. The challenge is abrupt and unprovoked, and it seems almost as if the two men are gambling for the right to carry off the young man. After he loses fifty dollars to the salesman, the man with the ruffled beard beats a hasty retreat.

Having vanquished his rival, the traveling salesman makes his move, offering to split his winnings—a substantial sum—with the youthful stranger he has just met. The young man declines to accept the money. The salesman insists. “You take half and I’ll take half, and we’ll go blow it. You’re as welcome as sunrise, my dear fellow. Take it along—it’s nothing. What are you kickin’ about?”

“‘No,’ said the youthful stranger with the blonde and innocent hair, to the traveler for the hat firm in Ogallala, Neb., ‘I guess I’ll stroll back up-town. I want to write a letter to my mother.’”

Crane, who gained a reputation as a superbly original prose writer, an author who employs startlingly odd images and unexpected phrases, concludes his report on the bathhouses of Hot Springs with perhaps the most peculiar sentence he ever wrote: “In the back room of the saloon, the man with the ruffled beard was silently picking hieroglyphics out of his whiskers.”

Whatever can that mean? What coded signals had he been sending to the youth that had been intercepted and repulsed by the traveling salesman? What odd ciphers had blown back in the thwarted man’s face? The narrator never says so, but it is likely that from his place at the end of the bar, Crane sensed he had witnessed one of the arcane rituals of a shadowy clan. He intuited that unwanted propositions had been made—and rejected—in a cryptic language of words and glances that he himself was unable to decipher with any degree of certainty. At their dinner at the New York hotel, the Painted Angel of Union Square may have shared many secrets about the hermetic world of homosexuals, but he had evidently failed to pass along the necessary Rosetta Stone.

We might have a clearer understanding of Stephen Crane’s meaning if the original manuscript for “Seen at Hot Springs” had survived—the article as Crane wrote it. The version published by the Bacheller syndicate begins with that odd observation (above) ending with the words: “he can conclude that he is a natural phenomenon and doomed to the curiosity of all peoples.” Surely “unnatural” would make more sense here, and if “unnatural” is what Crane actually wrote in the column he submitted to the newspaper, perhaps that censored “un” is all the Rosetta Stone we need to understand what he means.

References

Auster, Paul. Burning Boy: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane. Henry Holt, 2021.

Crane, Stephen. Crane: Prose and Poetry. Library of America, 1984.

Wertheim, Stanley and Paul Sorrentino. The Crane Log: A Documentary Life of Stephen Crane, 1871-1900. G. K. Hall, 1995.

William Benemann is the author of Unruly Desires: American Sailors and Homosexualities in the Age of Sail and Men in Eden: William Drummond Stewart and Same-Sex Desire in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade.