STORIES ABOUT GAY history often begin with a bar: the Black Cat in Los Angeles, Stonewall in New York. Equally important, our personal gay stories often begin with the gay bars of our youth. Yet these establishments are vanishing across the country for a variety of reasons, most prominently the rise of hookup apps like Grindr and skyrocketing rents for brick-and-mortar venues.

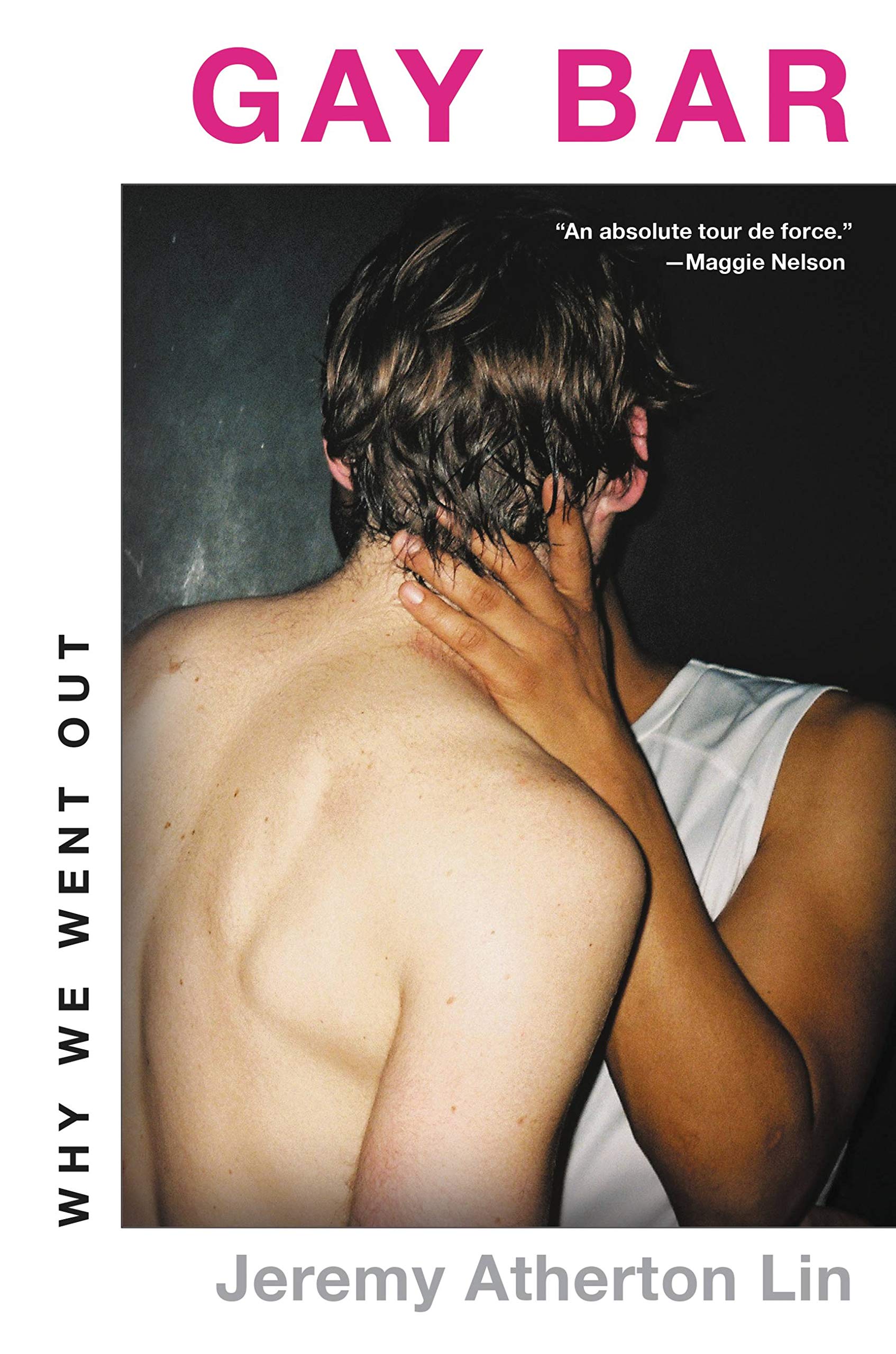

Does this disappearing act matter? That’s the question Jeremy Atherton Lin wrestles with in his ambitious new memoir cum cultural analysis, Gay Bar: Why We Went Out. In it, he examines the various functions that gay bars serve (as a refuge, for sociability, sex, and alcohol) and recounts the history of the ones he frequents in London, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Everything is viewed with cool detachment through the lens of his own biography. He analyzes his experiences as a representative of the larger group he identifies with, whether it’s London’s fashion crowd, the art queens of the Butt magazine era, or today’s politicized queers.

In the beginning (college in L.A. in the 1990s), Atherton Lin goes out to meet people, but the ones he meets don’t feel like the right people. A go-go dancer he dates suggests that Atherton Lin, a person of Chinese descent, should try wearing face powder to lighten his skin. The bars he frequents in this era are cheesy and the music they play is terrible.

He sees an advertisement for a London party called “Popstarz”—an image of lanky boys in plaid pants with tattoos on their arms and scowls on their faces—which represents a burgeoning ideal. Making his way to the club on a trip abroad, Atherton Lin finally feels at home. Having locked eyes with someone on the dance floor, he meets the man he’ll spend his life with. A true ’90s romance, their courtship is defined by love letters and mix tapes. Atherton Lin refers to his companion as “Famous Blue Raincoat” (after the Leonard Cohen song), “Famous” for short (and in the passages of his youth, simply as “the boy”).

If this strikes you as pretentious, know that Atherton Lin frequently and casually interrupts his narrative to write things like: “I thought of two lines from Paul Verlaine.” Imagine a person who pretends to keep accidentally bumping into you with a big stack of books, spines out, so that you can’t miss how wide-ranging his interests are.

As a couple, Atherton Lin and Famous go out in London and San Francisco for excitement: to dance, to engage in orgies, to find someone to bring home for the night. Yet the bars are frequently sad sack hangouts. They feel dispiriting and tacky, mausoleums to days gone by, enshrined in disco balls and rainbow flag bunting.

In addition to hooking up, going out casts a line for that most elusive catch of all, community, and sometimes brings the couple into contact with gay people of different generations. The older ones share stories and lament the scene’s changes; the younger ones seem to need something else: an inclusiveness that requires a lot of rules.

Each of the chapters is more-or-less devoted to one bar. The research Atherton Lin shares about their histories is sometimes interesting, yet its inclusion feels contrived. It’s not like he’s relating an oral history from interviews with the barflies. It’s like an information dump designed to make the book “relevant” in a way that perhaps Atherton Lin (or his publisher) worried his personal stories would not be on their own. But clearly the book’s main through-line is the first-person anecdotes and reflections.

While Atherton Lin seems well-trained in making cool, think-piece-like pronouncements about the state of the gay world, this detachment starts to feel like a kind of avoidance when he turns the lens on himself. He’s more comfortable writing about sex than love, thoughts than feelings. Gay Bar adopts a kind of intellectual posturing to mask the author’s vulnerability, youth’s self-conscious scowl now etching hard lines on the face. Occasionally, something authentic pierces the façade; and glimmers of the more intriguing, deeply personal book this could have been shine through: “I understood I’m the company I keep: a man over forty with a Friday night hard-on, passing as desirable in the dark.”

____________________________________________________

Michael Quinn reviews books for Publishers Weekly, literary journals, and the Brooklyn newspaper The Red Hook Star-Revue.