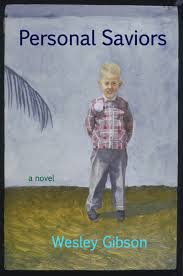

Personal Saviors

Personal Saviors

by Wesley Gibson

Chelsea Station Editions. 185 pages, $16.

“THAT WAS ALL he knew: what he was not. It seemed like perilous knowledge, and for years afterwards it would be.” These are the last words of the book under review—admittedly an odd way to begin a critique of this kind, but a fitting way to introduce Personal Saviors, a novel that skirts and subverts the norms at every turn.

Author Wesley Gibson follows eight characters through great personal transitions, which are staged in the deep South in 1969. Anti-war sentiment is boiling over, and the easy answers promised in the 1950’s seem like a fraud, at least to some, even as others cling to these shaky truths. Eleven-year-old Paul knows he’s different—wearing lipstick to bed, for example, to his mother’s consternation—and has alternately embraced this difference and thrown himself whole-hog into worship at a flat-broke fundamentalist church. The Reverend Farrel offers hope of redemption, but Paul is also harboring a dangerous crush on him. His new friend Denver isn’t helping matters by infusing their play with games of prepubescent sexual one-upsmanship, then trading Paul in for older, cooler, emphatically straight boys.

Paul’s home life is confusing at best. His mother Helen has begun to question the roles of wife and mother, and started playing guitar and singing, in a bid for a life of her own. Dad has gone from beer-drinking couch potato to UFO enthusiast, stockpiling provisions in case the aliens come and threaten America’s food supply. Both care for Paul, but only when it doesn’t interfere with their new passions.

Three female friends carry influence in Paul’s world. Lady is a byproduct of integration, the only black girl at their school and ready to get out any way she can. She forms a convenient alliance with Paul once she sees that he’s rejected by his schoolmates, but holds him at arm’s length, too. Velvet Archer, age thirty, has careened between men and alcohol her whole life. She loves Paul for his innocence and lack of judgment, and they hit the streets together, trying to win converts to the church and being chased away by folks who echo the sentiments of Paul’s mailman. When Paul inquires about the man’s relationship with Jesus as a lead-in to convert him, he replies, “We had a falling out.” Each failure hits Velvet like a body blow; she seems likely to leave the church for her old ways, since addiction began to lose its stigma in this time of peace and love.

The Reverend Farrel’s wife Millie is also a friend to Paul, one whose appearances in the book are so surreal as to raise the question of whether she’s authentic or a hallucination created for his own comfort. Gliding by on ice skates over the surface of a frozen creek, appearing as if from nowhere on a spontaneous hike, and literally dropping from the sky complete with parachute, Millie is kind and consistent in her treatment of Paul, even arranging to take him up in the plane she jumped from so he can be closer to God. The flight is revelatory for Paul, who sees that Millie is not the daredevil he’d taken her for. “She was frightened. All her antics were despite fear, or because of it; and Paul wondered how, given the proof of her love, God wouldn’t unburden her of it. He suddenly understood that there was no protection from the curse of desire. Salvation itself was desire. He had misunderstood everything.”

That passage is probably the book’s most gripping one, but it doesn’t lead to anything concrete. By the novel’s end, two characters have disappeared altogether, but even those tumultuous circumstances cause only ripples in the lives of this community; everyone is too preoccupied with their own progress or lack of it to expend much effort on behalf of others. That approach is one of the strengths of Personal Saviors. Rather than a simple snapshot of a time and place, which this also embodies, the novel is like a collection of character portraits. Things happen, people are affected, but it’s as if life itself is moving through the syrupy heat of high summer. The drama is muted, and we wonder how it will all turn out.

Paul’s realization in the plane and the loss of a friend eventually lead him away from the church. When the Reverend and his wife come to invite him back, claiming, “You’re ours,” he simply tells them, “We’re Episcopalian now.” They leave, and he’s left with nothing but the knowledge of “what he was not.” The words “for years afterwards” in the last sentence could be hinting at a sequel; and another visit with these characters would not be unwelcome, especially as they seem poised to navigate the 1970’s, and all that that implies.

________________________________________________________

Heather Seggel is a writer living in Ukiah, California.