IMAGINE YOU’RE A HOMOSEXUAL in the year 1882. You’re standing on a sidewalk in Louisville, Kentucky, in front of the office of George J. Monroe, MD. Dr. Monroe is a proctologist, and unfortunately you are in need of the good doctor’s services, though he is sure to ask you why you need to consult with him and how you got to be in the peculiar condition in which you find yourself, and you have no idea how he will respond if you tell him the gospel truth. You hesitate with your hand on the doorknob, sweating profusely, and you offer up a prayer that the proctologist will handle you with understanding and compassion. Imagine what your reaction might be if you knew that, at that very minute, Dr. George J. Monroe was sitting at his desk writing the following: “These habits are so abominable, so disgusting, so filthy, and worse than beastly, that the medical profession, from a sense of decency and respect, are loth to write about them, or even to discuss them with other physicians.” In 1882, you might have been disheartened—or perhaps amused—to learn that he then wrote: “There must be something extremely fascinating and satisfactory about this habit; for when once begun it is seldom ever given up.”

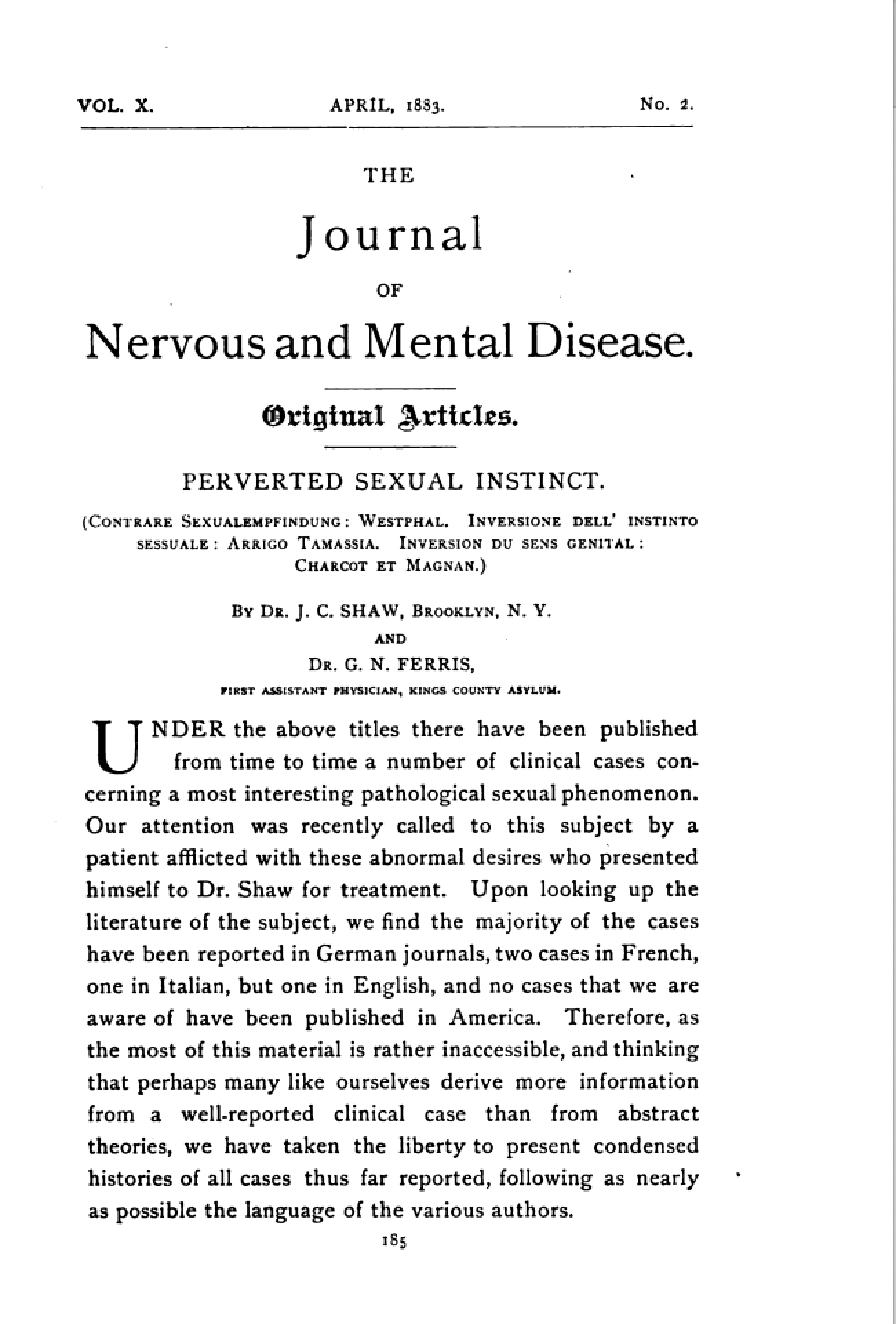

In late 19th-century America, most physicians shared Dr. Monroe’s revulsion at the very idea of same-sex activity, but an enlightened few noted that in Europe things were beginning to change, and they asked their fellow physicians to reconsider their loathing. In the spring of 1883 two New York doctors, J. C. Shaw and G. N. Ferris (it was the fashion to publish using only initials), contributed an article to The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease titled “Perverted Sexual Instinct.” In it, they reported on the number of case studies on the topic that had appeared up to that point: “[W]e find the majority of the cases have been reported in German journals, two cases in French, one in Italian, but one in English, and no cases that we are aware of have been published in America.” They then proceeded to describe a patient who had come to Dr. Shaw seeking treatment, a man who might be considered the first homosexual American to have his case described in a medical journal. By the end of the century, many more case histories of what would today be known as LGBT Americans began to appear in the literature, and while it took many more decades to complete the process, professional opinion about homosexuality began to change, however glacially.

While these case histories were rare, they were sought by homosexuals as one of the few ways to learn about the topic. As Dr. W. L. Howard explained of his patients: “They exist in both male and female societies and clubs, and by some subtle psychic influence these perverts recognize each other the moment they come in social contact. They are well read in literature appertaining to their condition; they search for everything written relating to sexual perversion; and many of them have devoted a life of silent study and struggle to over-come their terrible affliction.” Most case studies presented homosexuality as a “terrible affliction,” but they were a source of quasi-scientific data at a time when information was scarce, and it is easy to imagine these articles being passed from hand to hand by men and women eager to gain an understanding of their condition.

Not that they were all necessarily seeking a cure. Dr. G. M. Beard warned: “This class of people do not wish to get well. They are content with their lot, like the majority of opium-eaters and inebriates, and have no occasion to go to a physician; they enjoy their abnormal life, or, if they do not enjoy it, are at least not sufficiently annoyed by it, or are too ashamed of it to attempt any treatment. There are, as I have recently learned on inquiry, great numbers of such cases in the city of New York.” It was in New York City in the spring of 1880 that a man who refused to give his name or address came to the office of Dr. G. N. Shaw, and unknowingly became Pervert Patient Zero.

As described in the article by Shaw and Ferris: “A German, aged thirty-five years. Height, about five feet four inches. Weight, about one hundred and forty pounds. Black hair. Dark complexion. Well built. Physiognomy of an intelligent expression. Very reticent on some points of his history.” The patient would say only that he was “engaged in mercantile business” as a clerk, and he was distressed because he felt a nearly uncontrollable attraction to the men he worked with. He had never given in to his desires, but he feared that one day he might lose his self-control. “When in the presence of men, he is tormented by constant erections of his penis and a desire to embrace the men.” The patient had forced himself to have sex with women, but after three attempts he accepted that it gave him no pleasure. He was too ashamed to discuss his problem with his personal physician, “as he must consider him a horrible creature, and look upon him with disgust.” Thus he had come to a different doctor, one who did not know him, and he insisted on remaining anonymous.

Dr. Shaw wanted to make sure there was nothing physiologically wrong, and he asked the patient to undress for a physical exam. The result was the man’s utter humiliation. “At the time of examination penis is in full erection, and this patient says it is the condition of the organ whenever he is near men.” The man’s genital organ was “well developed.” In fact, everything about the man appeared outwardly normal. “Patient is an intelligent man, and perfectly natural in his appearance and manner, except that he is distressed by his abnormal state, and wishes medicine to overcome it.” But Dr. Shaw could offer no cure for the affliction, no pill to relieve the man’s distress, so the anonymous patient put his clothes back on, slipped out of the doctor’s office, darted stealthily out the front door, and disappeared into the streets of the metropolis, to remain forever nameless.

§

G. M. Beard, the doctor who acknowledged that there were homosexuals who “do not wish to get well,” reported on one of his patients. “I was at one time consulted,” wrote Beard, “by a man whose constant desire was to attain sexual gratification, not in the normal way or by masturbation, but by performing the masturbating act on some other person, and, in his case, it had become a mania practically, so that he was a great sufferer, and very earnestly sought relief.” Beard believed that many of his patients were unable to respond in an appropriate way sexually because of “nervous impairment,” a physiological blockage of the normal sexual response, causing a man’s natural desire to be channeled into unnatural acts. He theorized that electroshock treatments could remove that blockage. “One electrode in the rectum and the other in the urethra, both insulated nearly to their tips. In this method very mild currents must be used, since the tips of the electrodes come very near together, the tissues are very moist, and there is but slight resistance to the current.” Perhaps not surprisingly, the patient who sought treatment because he was drawn to masturbate other men ultimately declined Dr. Beard’s intervention: “I saw the patient but once, and do not know the result of the plan of treatment proposed.”

§

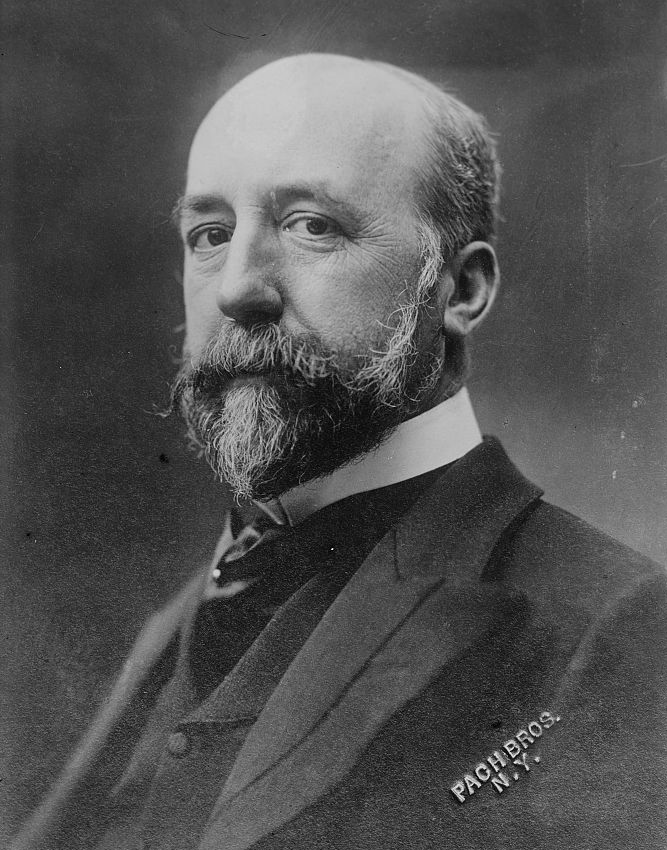

Dr. Allan McLane Hamilton, grandson of Alexander Hamilton, was physician to the best society families of New York, specializing in “nervous disorders.” In 1896 he published a case history that unfolded with all the restrained drama of a Henry James novel. Had James himself written it, the case history might have sounded something like this: A young heiress, referred to as “Miss A.” in the case study, had inherited a fortune of over a million dollars, but was now causing her family concern, so much so that they contacted Dr. Hamilton, who had earned a reputation, and the respect of New York’s legal community, as an expert witness in court proceedings, to intervene on their behalf, because to their distress the heiress—up until then meek and pious and content to allow her brothers, who were highly competent financial advisors, to invest her money for her—had, because she suffered from “trivial uterine disorders,” been induced by a friend to come to the city in order to consult a woman doctor, and now, to the consternation of her family, she seemed reluctant to return home. Concerned for her safety, and appreciative of Dr. Hamilton’s reputation for discretion when dealing, as he so often did, with the affairs of the elite of New York society, they had enlisted his aid as a last resort in their quest to convince the heiress to return to her family, or, failing that, to have a court declare her legally insane.

In his published case study, Hamilton reported on what he had uncovered about the gynecologist that the heiress had consulted. “The doctor was a large-framed, masculine-looking woman of about forty, with short, black hair, a raucous, deep voice, and a manner of talking which was in marked contrast to her patient, who was gentle and refined. When it pleased her she did not hesitate to emphasize her conversation with oaths, and affected the carriage and manner of an energetic and coarse man. Her attire even was affected, and was in harmony with her other peculiarities.” The young woman was treated for her gynecological problems for several months, with the relationship interrupted only briefly when the doctor decided to spend the summer in Europe. The patient returned temporarily to her family, but it was not a happy homecoming. “She was dejected, preoccupied, and constantly talked of the woman doctor in a way to tire the patience of those about her; but in a few months she become elated by the receipt of several letters and, despite the persuasions of her mother, returned to New York and went to live with her medical adviser.”

The family was alarmed when Miss. A. began to withdraw large amounts of her inheritance from her bank account, at the same time that the gynecologist began to build an expensive new house. Dr. Hamilton with great difficulty managed to schedule a consultation with Miss A., and was surprised by her attitude toward what he considered to be a loving family only trying to rescue their daughter and sister from a nasty predator. “On this occasion she manifested a great deal of hatred to her family, which was unreasonable, and avowed her loyalty to her ‘good friends,’ and ‘defied’ me to find her insane. No amount of reassurance and no appeal to her self-respect was of the least use, and she left me in an angry and obstinate mood. At this interview I was impressed with the peculiarity of manner and the intensity of feeling which might be exhibited by a woman who was defending her lover, and her defiant utterances were utterly unwarranted.”

Dr. Hamilton decided to hire a private detective to tail the couple, hoping to collect evidence that could be used in court. “The latter very diligently hunted up evidence, with the result that I learned that a veritable infatuation existed upon the part of Miss A., who went everywhere with [the doctor], and who even, at times, occupied her bed. Other information, of a more convicting kind, was subsequently ascertained, and was verified by letters that burned with love and had been written by the older woman to the girl. No lover could have expressed himself more ardently to his mistress, and there was no doubt but what the stronger woman had not only poisoned the girl’s morals, but had alienated her from her home and worked upon her for the purpose of getting her money, which she did.”

Dr. Hamilton was repulsed by what he learned, but reluctantly concluded that, while Miss A. was clearly deluded in her attachment to her female lover, she was not technically insane. “So far as the intellectual condition of the girl was concerned there was nothing in her conversation that would have convinced an ordinary jury that she was of unsound mind, and at that time her mental perversion was not of a recognized kind.” The amounts of money she had withdrawn from her bank account were indeed significant, but not really extravagant, given her large fortune, and she was legally free to spend her money in any way she chose. The best he could recommend to the family was perhaps to sue the doctor herself for “undue influence.” This they were reluctant to do, because such a dispute would necessarily lead to unpleasantness in the newspapers, and prove an embarrassment to the entire family. They thanked Dr. Hamilton for his tact and discretion, and left Miss A. to the woman she loved.

§

Dr. William A. Hammond, Professor of Diseases of the Mind and Nervous System at the New York Post-Graduate Medical School, represented perhaps the most typical response of American physicians when they were consulted by patients with “contrary” sexual desires. In 1883, Hammond published a case study of “a young man, twenty-eight years of age, [who]consulted me for treatment of pederastic tendencies to which he was subject, and to which he had repeatedly yielded, though always afterwards experiencing the most intense feelings of remorse.” (Here “pederastic” meant “homosexual.”) The man was well-educated, well-traveled, and “had ample means at this command,” and while he had repeatedly tried to divert his impulses by attempting to become attracted to women, he despaired that he was aroused only by men.

“The origin of the impulse was sudden,” reported the doctor, “and occurred when he was about twelve years of age. He had been severely flogged at school for some boyish offense, and soon afterward experienced in the sexual organs sensations which he had never felt before, accompanied by an erection which lasted fully half an hour. That afternoon, he went into a river near by to bathe, in company with another boy, and, while in the water, he swam with his hands resting on the other boy’s shoulders. He had often done this before, without having any sexual excitement provoked, but upon this occasion his penis came in contact with the gluteal region of his companion, and, instantly, he felt just such sensations as he had experienced when he had been flogged, and, like them, accompanied by an erection. They were close to shore, and before he knew what he was doing, he was performing a pederastic act.”

The students at the boy’s school engaged in frequent homosexual couplings among themselves, and after his initial encounter in the river, Hammond’s patient began to join in these activities, sometimes bottoming but usually on top. His feelings of guilt eventually prevailed though, and for his four years of college, he remained entirely celibate. “He, however, frequently practised masturbation, and during the act always directed his mind toward the subject of the gluteal region of man, of naked men, and images of men committing pederasty. There was scarcely a night that he did not commit self-pollution. Nocturnal emissions, also, were common, and were always accompanied by lascivious dreams, of which pederastic acts were the principal features.” The patient avoided the company of “virtuous women” because he felt he was morally unfit to associate with them, and since he could not allow himself to act on his desires, he developed instead a vivid fantasy life. “For instance, he spent the whole of one evening drawing the gluteal regions of the great men of the world, and imagining that he was having pederastic relations with them.”

But the suppression of his desires could not be sustained forever. “Soon after leaving college, while stopping at a hotel in this city, a telegraphic message arrived for him late in the evening, just as he had undressed, and was going to bed. The bell-boy of the hotel, who brought it to him, was a rather handsome lad, and excited the desires of the patient to an inordinate degree. He offered him a considerable sum of money to remain with him all night, and, without much persuasion, consent was obtained. He had never experienced such intense venereal excitement as he did that night, and he committed pederasty eleven times before morning.” The dam had broken, and the patient later engaged in sex with men several more times until, overcome with guilt and shame, he came to Dr. Hammond’s office, seeking a cure for his troublesome desires. The patient had met a young woman and wished to marry her—though he felt no sexual attraction to her at all. Could the doctor please help?

“I advised continuous association with virtuous women, and a system of severe study of subjects that would require abstract thought of the highest kind. I suggested mathematics. He at once agreed to pursue the exact course I marked out for him in these respects. I also recommended cold baths every morning, a liberal diet, and plenty of outdoor exercise, either of walking or horseback-riding.” The doctor also cauterized the nape of the man’s neck and his lower back, and began administering doses of sodium bromide, an anticonvulsant and sedative meant to deaden his sexual desires. After three months of burning and drugging, success of a type was achieved. “Bromism had been produced to a tolerably severe degree, and with its appearance, the unnatural proclivities towards men began to disappear. He no longer had images, such as had formerly haunted him, passing through his mind, and he could look at a nude statute [sic]of a man without feeling any sexual excitement.” There was only one problem: “He had not, however, had any inclination towards women.”

Dr. Hammond still viewed this as progress, though, and feeling that the patient “had obtained such a degree of control over himself, as to prevent his returning to his former habits,” he halted the bromide treatments and switched instead to a mild tincture of strychnine. “During this period he had no relapse. The images, which formerly excited him now disgusted him, for he associated them with some of the most remorseful feelings a man could have, and he had begun to take pleasure in the society of respectable women. He had not, however, experienced any but the faintest evidences of sexual excitement, though occasionally he had felt slight normal desires.”

The treatments were begun in the spring of 1882, and over a year later, having in effect been chemically castrated, the patient “was strong and healthy, free from all pederastic tendencies; in fact, entertaining the liveliest disgust for it, and thinking seriously of marriage.” He assured the doctor that he had had “several times, natural sexual desires, accompanied by erections, but a high sense of morality, which now exists in him, has prevented any yielding. He has nerve to keep himself perfectly chaste till his marriage, and then to use with discretion whatever power he may have.” Dr. Hammond, having presented what he clearly viewed as a success story in treating a homosexual patient, rang down the curtain at this point—yet it is easy enough to predict what was likely to happen in Act Two.

European doctors were in the forefront when it came to treating sexual minorities, but by the early 1880s, some American doctors were stumbling not far behind, pulled along by patients who had already devoured the latest European medical reports and were eager to have their cases treated with understanding and compassion. Advances in American medicine were uneven, but whether a doctor shocked a man’s genitals or drugged him into becoming a eunuch, the profession at last began to accept that the problem was not in their patients’ weak wills or corrupted souls. Acceptance of homosexuality was definitely not part of the medical protocol, but for more and more doctors, their patients’ abnormal behavior was considered to be merely misdirected, not disgustingly wicked.

Reading these case studies from the late 19th century is like watching a drama that is unfolding behind a thick layer of translucent glass—we can see only vague shapes and movement, hear only muffled voices. We catch glimpses of these very real people, but their stories are being relayed to us at a distance, by doctors whose attitudes range from hostile to clueless. Still, early case histories can provide windows into the lives of everyday Americans whose stories appear nowhere else. The reports are flawed and prejudiced and incomplete, and yet here and there the humanity comes through, the blurred comes into focus. We cheer the defiance of the young lesbian standing up to her family, determined to share her life with the woman she loves. We empathize with the embarrassed clerk desperately trying to hide his erections from his handsome co-workers. With the bachelor in bed with the bell-boy we celebrate the volcanic release of pent-up desire—eleven times in one ecstatic evening!

References

Beard, G.M. Sexual Neurasthenia (Nervous Exhaustion): Its Hygiene, Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment, with a Chapter on Diet for the Nervous. E. B. Treat, 1884.

Hamilton, Allan McLane. “The Civil Responsibility of Sexual Perverts,” in The American Journal of Insanity, vol. LII (1895-1896).

Hammond, William A., Sexual Impotence in the Male. Bermingham & Co., 1883.

Shaw, J.C., and G.N. Ferris. “Perverted Sexual Instinct,” in The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, vol. 10, no. 2 (1883).

William Benemann is the author of Unruly Desires: American Sailors and Homosexualities in the Age of Sail, and Men in Eden: William Drummond Stewart and Same-Sex Desire in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade.