Tseng Kwong Chi: Performing for the Camera

Tseng Kwong Chi: Performing for the Camera

Tufts University Art Gallery,

January 21 to May 22, 2016

Exhibition Catalog

Chrysler Museum of Art/

Grey Art Gallery/Lyon Artbooks

BACK IN THE DAY, SoHo was a dirty place. Young refugees from the provinces squatted in cold-water lofts, went to parties, saw all the best bands, and made great art. You really had to be there. Actually, it was a little more complicated than that, but the myth of downtown New York in the 1980s stands on a factual foundation. From a trove of over 100,000 photographs—the massive archive of artist Tseng Kwong Chi—comes this powerful new exhibition and catalogue. Known in his lifetime as a photographer, Tseng emerges from this show as a radical innovator in performance art—playful, campy, and utterly unforgettable.

Tseng moved between worlds, both geographic and artistic. Born in Hong Kong in 1950, he migrated with his family to Vancouver and settled in New York in 1978, where he shuttled between his own photographic practice, freelance work for the alternative press, and shoots for glossy fashion magazines to pay the bills. He built a bridge between the shiny world of Andy Warhol and the grittier East Village by turning his life into a work of art. Of course he wasn’t the first to do so (Oscar Wilde, call your office), but coming a generation after performance art codified itself as, well, a thing, Tseng took the medium in new directions. At times, he fabricated from whole cloth, as when he donned a Zhongshan suit (known in the U.S. as a “Mao suit”) that convinced strangers he was a visiting Chinese dignitary. The ruse worked, paradoxically giving him access to spaces generally closed to outsiders—though if they’d bothered to read his lapel badge, they would have seen below his photograph the job title “slutforart.”

At times, Tseng deployed his persona to afflict the comfortable, donning preppy duds in 1981 to trick members of the Moral Majority into posing before a crumpled American flag. A year earlier, Tseng brought his press credentials to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual high-society gala for the Costume Institute, where he snapped photographs of himself in Chinese dress together with attendees whose orientalist couture hovered between vaguely racist and totally preposterous. Sometimes, though, Tseng boldly pursued life not to make a work of art but simply because living was so much fun. He really did see all the best bands and knew everyone before they were famous. Most notably, Tseng collaborated closely with street artist Keith Haring, regularly serving as Haring’s designated photographer to record the latter’s evanescent graffiti actions.

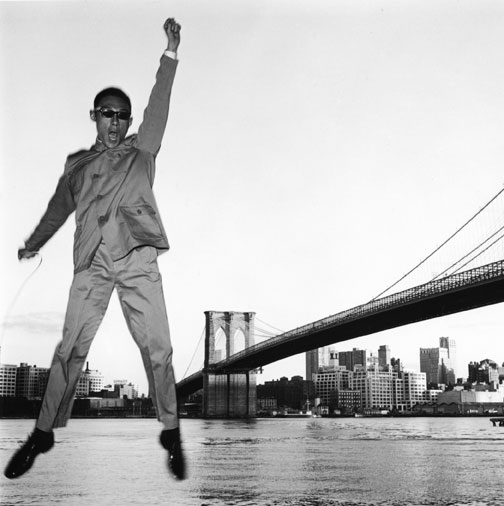

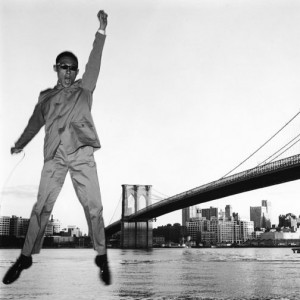

Along the way, Tseng made some deadly serious—yet simultaneously very funny—photographs. In his “Expeditionary” series, Tseng situated himself in iconic landscapes, both urban and rural, from the Eiffel Tower and the Brooklyn Bridge to the Grand Canyon and the Canadian Rockies. We know these places, and yet, as Tseng forces us to see them in new ways, we don’t. At times filling the frame with his body and displacing the icon, or documenting nature’s grandeur while miniaturizing himself, Tseng’s playful reworkings of scale generated an anti-heroic position that is visually stimulating and intellectually provocative.

Tseng once described himself as an “inquisitive traveler, a witness of my time, and an ambiguous ambassador.” But wait, what’s the difference? And what did it matter that he was gay and Asian? Tseng’s persona functions as old-school camp and also lends itself to a queer-of-color critique in which his deliberately anomalous gay Asian presence unsettles the iconic nationalist landscapes he depicts. In the exhibition catalogue, scholars Alexandra Chang and Joshua Takano Chambers-Letson take up the possibilities (and limits) of such readings. Tseng’s photographic archive likewise makes its own contribution to queer history, documenting the formation of a community of artists later devastated by AIDS, including Tseng himself, who died in 1990.

Initiated at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, and recently installed in a spacious gallery at Tufts University in Boston, Tseng Kwong Chi: Performing for the Camera features more than eighty of Tseng’s large-format black-and-white landscape photographs, as well as color portraits of artists such as Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Supplemented with artifacts—contact sheets, artists’ books, magazine spreads—and a 1980s soundtrack, the show documents Tseng’s working process and conveys the visual culture of the period. Past exhibits of Tseng’s art have depicted him as an adjunct to Keith Haring’s practice, or focused on his highly polished art photographs. This exhibit shows instead that Tseng’s work is, as curator Amy Brandt puts it, “less about the final image as a work of art than the artist’s act of setting the stage for his own performances.”

Christopher Capozzola is an associate professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.