ERIC RHEIN: Lifelines

ERIC RHEIN: Lifelines

by Paul Michael Brown, Mark Doty, and Eric Rhein

Institute 193. 112 pages, $45.

A HANDSOME, hardcover book, bound in grey cloth with a black leaf on its cover, opens to a mellowed color photograph of an artist’s studio. Delicate wire structures stand inside thick Plexiglas boxes, while more robust specimens, including what looks like a headless bust in a corset, are arranged in the middle of the room on a cloth-covered table. Hung on the wall, and leaning against it, are framed black-and-white portraits. In one, a naked man with an erect penis leans against a branch. In another, a naked man sits on the ground, his back against a tree. In a third, a man faces away from the camera, his naked back covered with what look like lesions.

The monograph Eric Rhein: Lifelines collects ideas and images related to a 2019 exhibition of the Appalachian native’s work at Institute 193 in Lexington, Kentucky. It successfully captures the elegant, elegiac mood of Rhein’s art, especially in these portraits of (often nude) men taken between 1989 and 2012, and in the delicate wire sculptures from an ongoing series, “Leaves,” each a memorial to someone Rhein knew who died from AIDS. (Rhein was diagnosed with HIV in 1987, at the age of 27.) The simple, strong lines convey specificity, yet there’s no elaboration on why a specific leaf was chosen to memorialize a particular person, or if some people belong to the same kind of tree—a missed opportunity.

Accompanying the photographs are three essays: by former Institute 193 director Paul Michael Brown (who mounted Rhein’s show), by poet Mark Doty, and by Rhein himself.

In “Lifelines,” Brown recounts a visit to Rhein’s Jersey City studio. “Nothing is out of place—all is arranged with meticulous grace.” Their recalled conversation touches on queer history, shared Southern roots, and ideas about family.

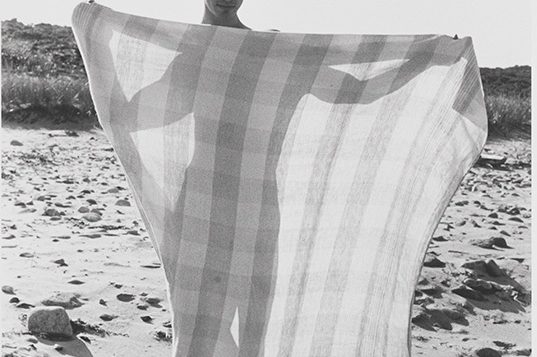

Martha’s Vineyard), 1992.

When Rhein shows Brown his portraits—sinewy young men, sometimes with pierced ears, nipples, and penises—he calls them by name: “William, Jeffery, John, Andrew, Joe, Russell.” Some were lovers, some friends. Some are living, some are dead. Self-portraits show Rhein sitting or lying nude on a primitive wooden bench. At other times, he appears next to his subjects, kissing them in a rumpled bed, or helping to insert an IV.

Another photo from Rhein’s studio demonstrates his interest in the natural world: a chipped green box is full of dried leaves, antlers, curls of bark, the dried honeycomb of an insect nest. An open cabinet drawer reveals rusty metal hardware, organized by shape, which Rhein employs in his meticulous sculptures. While some are free-standing, others spring off found pages from medical books, both interrupting and changing their intended narratives.

Yet the work never feels playful, which is why the jaunty tone of Doty’s essay, “On Eric Rhein: Maps and Treasures,” in which Doty compares a young queer person’s search for identity to a Nancy Drew mystery, feels tone deaf to its surroundings. Of a visit to his uncle that Rhein took as a young boy, Doty writes: “Lige became a guiding spirit, and after his death, Eric found a legacy”—two books his uncle had written with his partner about their life together in New York City and a copy of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Doty seems excited about the chance to talk about Whitman, less so about Rhein. The nature of their relationship is not made clear.

Rhein’s own essay, “Notes From My Tree House,” closes the book, though it might have made more sense to open with it. Living in an East Village apartment “at the level of the scholar trees” outside his window, he recalls his mother’s tender care when he was first sick from HIV. She “looked up from where she was making chicken soup to see me through my bedroom door, emaciated and injecting medications into my thigh. Our eyes met for a second, long enough for me to see her gasp and cry. But we pretended I hadn’t until later—when, over soup, she shared that the tears were for seeing her son as if he were an old man.”

Protease inhibitors saved Rhein from death, but they did not bring him back from the dead. This man is haunted. His work might be the stronger for it, but it has definitely come at a price. Marveling at the young people of today, Rhein wonders if they’re reincarnations of those who died from AIDS when he was young. When a Buddhist friend supports this idea, Rhein writes: “the hair on my arms stood up, affirming, confirming”—the body testifying for what the mind can never know.

Michael Quinn reviews books for Publishers Weekly, for literary journals, and for his own website at mastermichaelquinn.com.

Discussion1 Comment

In the middle of his review of Eric Rhein’s book “Lifelines,” Michael Quinn complains that an essay Mark Doty wrote for the book has an out of place “jaunty” tone and that Doty seems “more interested in talking about Whitman, less so about Rhein.” I disagree. Doty writes about challenges posed to queer artists and writers, particularly in the age of AIDS – the tone is hardly “jaunty.” As for Whitman, there is a reference to a particular photograph by Rhein that echoes a Whitman sensibility which I read as giving Rhein high praise indeed. Check out the Doty essay for yourself. Louis Wiley, Jr

https://www.manacontemporary.com/editorial/maps-and-treasures-from-eric-rhein-lifelines/