MORE BUTCH HEROES

MORE BUTCH HEROES

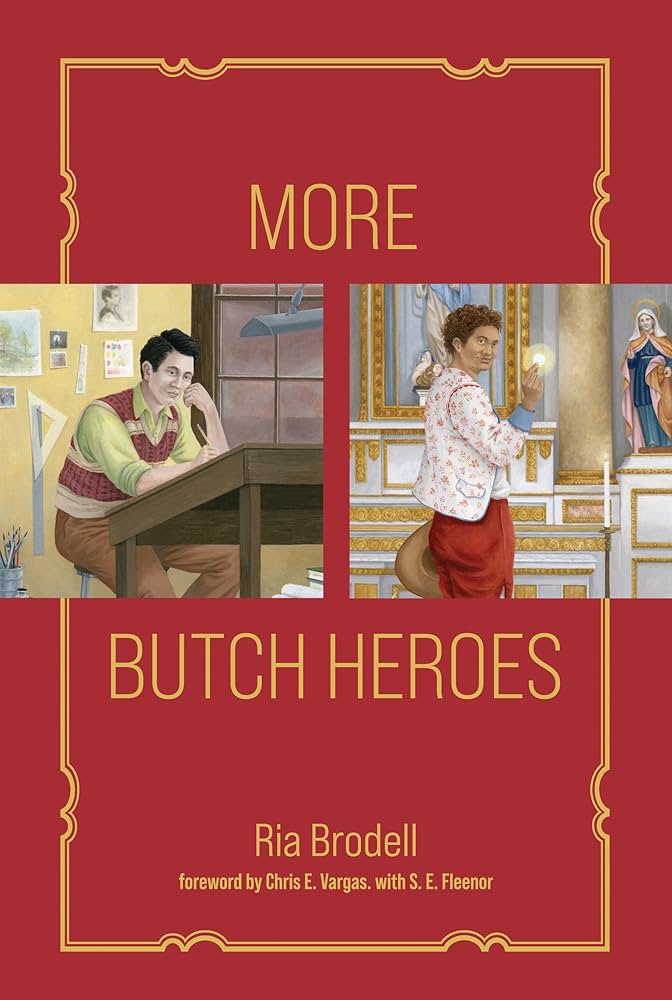

by Ria Brodell

MIT Press, 96 pages, $24.95

AS QUEER PEOPLE, we seldom learn our community’s history through the same channels as our straight siblings. Instead, we must seek it out ourselves and either rely on published histories or piece together our own research. Finding LGBT historical figures before the mid-20th century who were not white, cisgender, or bestowed with significant privilege is especially difficult. Queer historical figures often fall into two categories: those who had the safety or social cachet to tell their own stories, or those whose lives were recorded only because they were caught, institutionalized, or sensationalized. More Butch Heroes, Ria Brodell’s sequel to their 2018 book Butch Heroes, uncovers and memorializes historical gender-nonconforming figures, affirming that queer and trans lives today are not new but the continuation of a once-hidden legacy.

Claiming this lineage is at the heart of Brodell’s project, which began fifteen years ago with a self-portrait of the artist imagined as a 13th-century nun or monk—decidedly butch regardless of monastic label. The project soon grew into an archive of more than two dozen “butch heroes” that Brodell, who was raised Catholic, subversively transformed into religious icons. The main criterion for inclusion in the first book was that the figures resonated with the artist’s own experience. They sought out people assigned female at birth who had documented relationships with women and whose gender presentation was more masculine than feminine. More Butch Heroes adds fifteen new portraits styled as Catholic prayer cards to the deck.

More Butch Heroes continues Brodell’s visual storytelling but broadens the first volume’s strict research criteria. The new figures are not well-documented but instead people whose stories have survived despite being obscured in the historical record due to racism, sexism, or colonialism. The portraits feature Indigenous people, heretics, miners, cross-dressers, artists, singers, parents, thieves, curators, and formerly enslaved people whose names were never recorded.

These figures include Gregoria, aka la Macho, who was arrested in Mexico City in 1796 for the sacrilege of taking Communion while dressed as a man. They’re depicted mid-crime, smirking over their right shoulder, holding the shining Eucharist aloft in front of a statuette of the Virgin Mary. Their expression is mischievous: the viewer is either meant to be in on the prank or scandalized by their insolence. “Name Unrecorded,” aka Papa, is documented in a brief 1879 newspaper article describing “a colored woman here who was raised as a boy,” dressed as a man, and was caring for a small child. Their names are not recorded and their lives are lost to history. The only personal fact shared is particularly intimate: the child called them Papa. In Brodell’s illustration, Papa stands proudly but defensively, with his hands on his hips and feet planted wide, while the child peeks out from behind his leg.

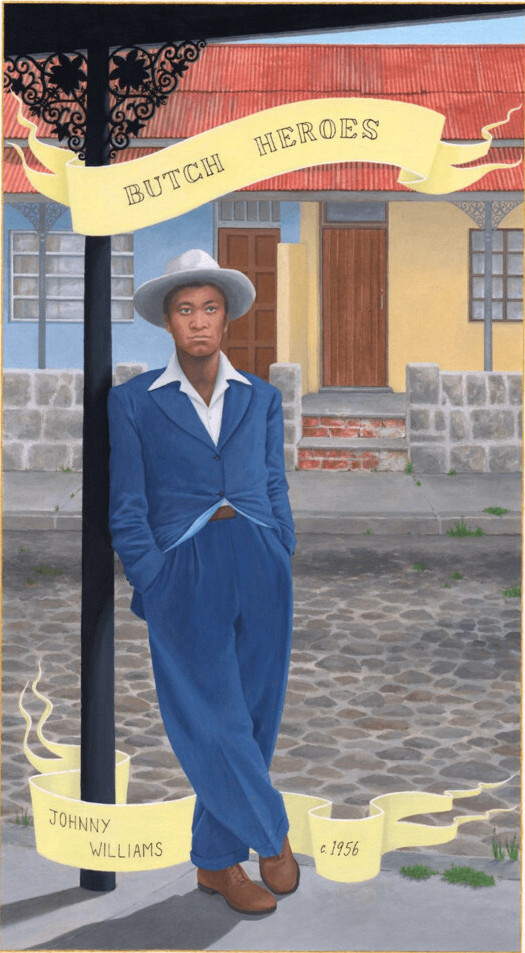

Johnny Williams, a roguish Black tomboy born in South Africa around 1930, flashes a cocky smile while wearing a handsomely tailored blue suit. Though he appears confident, his story reveals deep anxiety about his gender—he longed for God’s intervention to “become a whole man,” and feared he would never marry or raise children after his partners discovered his sex. Esther Eng, aka Brother Ha, smiles widely at the viewer while standing beside her camera with San Francisco’s Mandarin Theater in the background. Eng’s experience is almost normalized—she never hid her relationships with women and found success as a Cantonese-language filmmaker and restaurateur in the mid-20th century.

Although the stories of these figures are short and some end in punishment, imprisonment, or death, their lives still inspire hope. In their way, these butch martyrs are a miracle: a reminder that despite gaps in the records, we have always existed. More Butch Heroes reminds me of Sappho’s poetry—only fragments of the original lesbian’s writing survived antiquity, but those remnants inspired Oscar Wilde’s aestheticism, Renée Vivien’s romanticism, and generations of queer artists, writers, and historians. Reading More Butch Heroes, I can only imagine whom Brodell’s work will one day inspire.

_________________________________________________________________

Joan Ilacqua is a public historian and executive director of The History Project, Boston’s queer community archives.