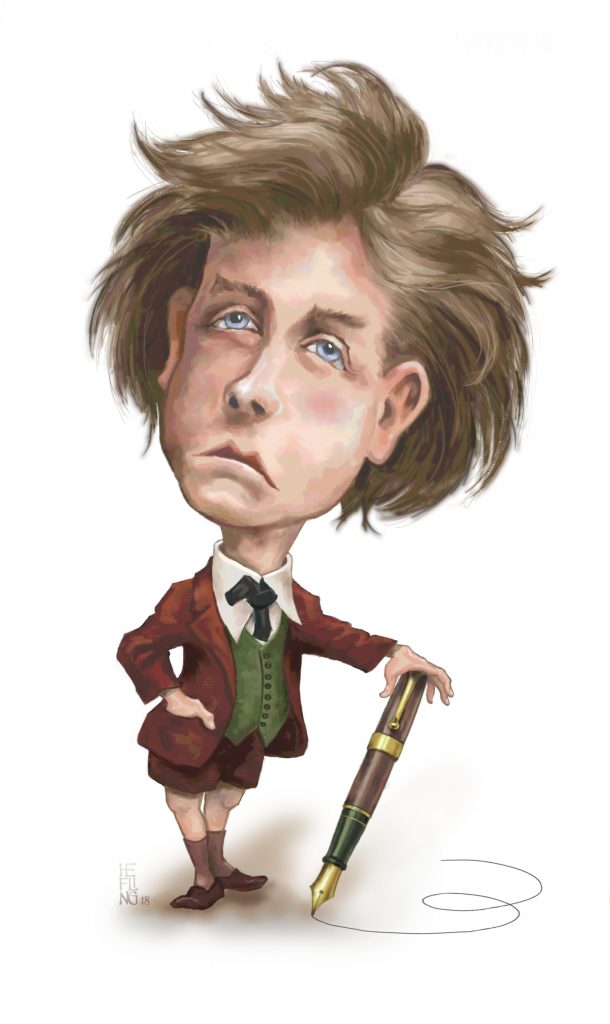

A GIFTED GOOD-FOR-NOTHING, a dazzling poet who wallowed in filth, a queer rock star before such a thing existed—Arthur Rimbaud was nothing if not an original. Although he established himself as a founding member of the French Symbolist movement thanks to the innovative and irreverent quality of his work, Rimbaud can neither be defined nor judged on one scale alone. Indeed, this literary trailblazer—described by critic David Steel as a ticketless passenger on an end-of-the-century poetic journey, sometimes a scoundrel, sometimes a seer—was a loose cannon who did whatever he pleased, offering little deference to the stifling rules of contemporary Parnassian society. His literary career, a supernova of light and darkness, of genius and filth, only lasted a few frenetic years before he decided to go traveling the world. But during this all-too-short period he reached a zenith of creativity, leaving behind a cache of literary jewels for an audience mesmerized by their sparkling, salacious beauty.

But what does Rimbaud mean in the context of LGBT history and how we view it today? We have our icons, our activists, our trailblazers who have fought tirelessly for society at large to accept us as “normal.” Then we have a character such as Rimbaud, who had nothing but contempt for social convention, alienated even his friends, and stuck out like a sore thumb. A close reading of the life and work of Rimbaud reveals a liberated worldview and unexpected homoeroticism that may surprise and shock even a contemporary audience—and highlight the need for our community to embrace the unique nature of our queer experience in the 21st century.

Rimbaud was born in 1854 in Charleville, a town located in the north of France. One would never have expected this social dissident, who thumbed his nose repeatedly and energetically at his straitlaced contemporaries in his late adolescence, to have had such a dull and domestic childhood. Nevertheless, the young Arthur, back then a pale and inoffensive child who was bullied by his classmates, lived under the heel of his mother, whom he called “la bouche d’ombre”—“the mouth of shadow”—a domineering woman who insisted on a classical and religious education such that the poor boy did little more than study. However, the fact that his mother kept him on such a short leash might well have been the main reason for his developing the rebellious streak and wanderlust that would lead him to the heart of Africa and beyond.

The young Arthur was taken under the wing of his teacher, Georges Izambard, and the two developed a very close relationship.

Rimbaud’s life was profoundly changed when he met the poet Paul Verlaine, a founding member of the Symbolist literary movement. The Symbolists sought to revolt against the hegemony of naturalism and realism at the time, to put forth a spiritual conception of the world, and to find other means of expression to surpass simple realist representation, using images and analogies to evoke the otherworldly and to suggest states and abstract ideas without explaining them. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this form of poetry appealed to the young iconoclast, and he plunged into the movement headfirst, enriching it with his own unabashedly vulgar style.

The two poets began a tumultuous relationship, full to the brim with brawls, alcoholic foolishness, and above all a sexual passion that brought them to the heights of ecstasy and the depths of despair. In the eyes of the young Rimbaud, Verlaine was at once a friend and colleague, a father figure, and a lover, taking Rimbaud all the way to London, to Belgium—and almost to the grave. In a fit of rage, Verlaine once shot Rimbaud, injuring the latter’s arm. Although they rocked the French literary world with scandal after scandal, they also made creative magic. The two poets, who were said to make love like tigers, injected the Symbolist movement with a creative energy that it had never known, and would never know again.

Literary success and romantic passion were not enough to satisfy Rimbaud, who as a child learned Arabic and German for the fun of it and dreamed of adventure in faraway places. No sooner had Rimbaud shot to the top of the literary world than the capricious youth decided to abandon literature and travel around the world. During his travels, he visited thirteen countries and even stayed for a time in the so-called “forbidden city” of Harar, Ethiopia, the first European to do so. But the spring of youth eventually gives way to winter: nearly thirteen years after renouncing literature for world travel, he found himself writing again, but this time a letter to his sister Isabelle while lying on his deathbed. He died of cancer soon thereafter at age 37.

The works of Rimbaud are diverse, of wide formal and thematic breadth, a menagerie that may show sometimes an intellectual and philosophical virtuosity, sometimes a flagrantly visceral sexuality coated in a scatological varnish. In “Mauvais sang” (“Bad Blood”), the first section of his extended poem Une saison en enfer (“A Season in Hell”), he demonstrates the depth of his intelligence and his capacity to consider the world from a philosophical, metaphorical, sociopolitical point of view. This work employs a narrator, a commoner who suffers from a “perfidious tongue”: the sign, it seems, of his “bad blood.”

The use of stigmatized language allowed Rimbaud to discuss the relationship between poetry and French social roles after the Revolution, calling into question the ideal of a “language in liberty” that cannot be separated from the social economy of the time. Here the narrator has difficulty creating an identity for himself, be it personal or national, because of the blending of past and present that follows from the fundamentally static nature of our conception of history. This work is thus a social commentary that exhales a lightly fatalist perfume, a thoughtful reading of an identity crisis issuing forth from an event that irrevocably changed the face of the French nation.

His poem “Voyelles” is quite different in form and scope from “Mauvais sang.” What emerges as most salient is the use of synesthesia, a blending of the senses that could cause someone to experience musical notes as different shapes or letters of the alphabet as having distinct colors or even as endowed with their own personality:

A black, E white, I red, U green, O blue: vowels,

I shall tell, one day, of your sleeping provenance:

A, a black velvet corset of shimmering flies,

Who buzz around cruel stenches

Gulfs of shadow: E, innocence of vapors and tents

Lances of proud glaciers, white kings, shivers of umbels;

I, purples, spat blood, smile of beautiful lips

In the anger or the inebriation of penitence;

U, cycles, divine vibrations of viridian oceans,

Peace of pastures sowed with animals, peace of the ripples

That alchemy stamps on great studious foreheads;

O, supreme Horn full of strange cutting sounds,

Silence traversed by Worlds and Angels:

O the Omega, violet rays of His eyes!

In the first verse of the sonnet—“A noir, E blanc, I rouge, U vert, O bleu: voyelles” in the original—the reader is invited to see the five vowels through the author’s poetic eyes. These letters, moreover, are not simply carriers of pigment but also characters in their own right, each with its own complex personality. The poem becomes a primer on the use of symbols, and their power, in the poetic movement with which Rimbaud was affiliated.

But there is another side of Rimbaud—the dirty side, the bawdy, the vulgar, the puerile, the one we hide but should remember—which manifests itself most clearly in a sonnet written with his accomplice Verlaine: “Sonnet du trou du cul” (“Sonnet of the Asshole”):

Dark and pleated like a violet carnation

It breathes, cowering humbly in the moss,

Still moist from the love that sweetly follows

Those white Cheeks to the heart of its rim.

Filaments like tears of milk

Have wept, beneath the cruel gusts that push them

Through the little clots of red mudstone

To lose themselves where the slop calls them

My Dream did often join its suction cup

My soul, which envies worldly intercourse,

Makes of it tawny nettles and its sobbing nest.

It is the swooning olive and the inviting flute

It is the tube where the celestial sweets descend

The Female Canaan rimmed in dew!

Verlaine contributed the first two quatrains, in which the physical images of a countryside predominate, while Rimbaud contributed the two final tercets, which are instead characterized by spirituality and synesthesia. The content is explicitly homoerotic, referencing anal sex and the authors’ passion for it. This work is meant to be humorous and to shock an audience that was accustomed to realism. However, despite its absurdity, the poem displays a symbolic beauty that is characteristic of the movement and its goals, proof that the Symbolists could broach any topic they wished.

Rimbaud was a queer character in all senses of the word: a gay man who reveled in his gayness, a beautiful dichotomy who was at once sophisticated and intellectually complex—passionate about languages, of which he spoke a few—and rude, insensitive, and repugnant, according to the majority of people who knew him. He delighted in all manner of depraved practical jokes at the expense of both his friends and rivals. Nevertheless, he had an open spirit, appreciated other cultures, and endowed his work with a profound intellectual sensibility that belied his young age. This captivating duality, this cavalier disregard for both heterosexual convention and etiquette, is the best proof that Rimbaud was not simply an author; he was an experience.

LGBT historical figures are not always the best role models for today’s gays. Although we’d like to be able to place our more illustrious pioneers and activists at the forefront of LGBT historical identity, we should not shy away from our darker, more salacious or forbiden side. LGBT identity, after all, is also a political issue: it stands in direct opposition to hegemonic heterosexuality and is transgressive at its core. When we reflect on our history, which we should do often, we would do well to think not only of people like Marsha P. Johnson and Harvey Milk, but also of people like Arthur Rimbaud: those who have challenged the oppressive status quo by reclaiming the spaces that were once off limits and embracing the language that used to be taboo.