Fatal Glamour: The Life of Rupert Brooke

Fatal Glamour: The Life of Rupert Brooke

by Paul Delany

McGill-Queen’s University Press

380 pages, $34.95

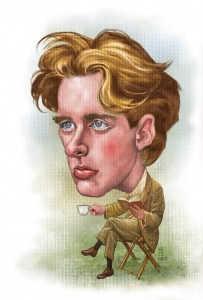

RUPERT BROOKE is one of those figures who continually haunt the periphery of literature, a figure of myth and uncertainty. Chief among his attributes is that he is forever linked with the generation of English poets who perished in World War I (Brooke died at Gallipoli, at the age of 26). Simultaneously—and almost inextricably—he is almost as well known for his physical attractiveness as for his poetry. Leonard Woolf summed it up in this way:

His looks were stunning—it is the only appropriate adjective. When I first saw him, I thought to myself: “That is exactly what Adonis must have looked like in the eyes of Aphrodite.” It was the sexual dream face not only for every goddess, but for every sea-girl wreathed with seaweed red and brown and, alas, for all the damp souls of housemaids sprouting despondently at area gates.

If Brooke’s face was all that for young women, he was no less attractive to the gay men of the time, many of whom he was friends with, and at least one of whom he also had sex with. But Brooke was never easy with his sexuality—either straight or gay. Indeed, one of the things that emerges from Paul Delany’s exceptionally thorough biography is how very conflicted Brooke was about nearly everything.

A product of his time and upbringing, Brooke attended the Rugby and Hillbrow schools with James Strachey and Robert Graves. He was also friends with the Bloomsbury set, as well as with Darwin’s grandchildren, among numerous other notables. Two of the features seemingly endemic to the public (i.e., private) school experience at this time—at least for Brooke—were relentless indoctrination concerning students as the champions of England’s future and a hidden culture of homosexuality. One’s induction into both areas could be brutal: school itself was a daily preparation for England’s future warriors, and Brooke reports that there were gang rapes of younger students as an initiation ritual.

Brooke was a participant in all this, but also a conscious rebel. Along with a group of friends who were dubbed by Virginia Woolf as the “Neo-Pagans,” Brooke and his friends sought to slough off what they saw as the shackles of Victorian morality and conventions. Brooke took this to the extreme of wearing homespun clothing, going shoeless, and sleeping outdoors at night on the grass. But for all the Neo-Pagans’ professed enlightenment about sex and their disdain for Victorian prudery, Brooke was never entirely comfortable with overthrowing social conventions; nor, for all his apparent courting of the “young Adonis” image, was he ever completely at ease with being perceived as an object of desire. Indeed, Delany convincingly links his beauty, this “fatal glamour” of Brooke’s, to his untimely demise.

Much has been made of the apparent crisis of masculinity that surrounded the advent of the War. The traditional roles of men were changing from those of a largely agrarian society to those of urban industrialism. In such an arena, the call to war gave men who viewed themselves as displaced a new sense of purpose—one founded upon traditional notions of what a man was supposed to be and do. In Brooke’s case, it fit perfectly into the psyche of someone who was always uncertain about his sexuality, who could profess free love, on the one hand, but retain a sentimental attachment to traditional values such as celibacy before marriage. It may also have been an escape hatch from the need to come to terms with his own same-sex feelings and inclinations.

Much has been made of the apparent crisis of masculinity that surrounded the advent of the War. The traditional roles of men were changing from those of a largely agrarian society to those of urban industrialism. In such an arena, the call to war gave men who viewed themselves as displaced a new sense of purpose—one founded upon traditional notions of what a man was supposed to be and do. In Brooke’s case, it fit perfectly into the psyche of someone who was always uncertain about his sexuality, who could profess free love, on the one hand, but retain a sentimental attachment to traditional values such as celibacy before marriage. It may also have been an escape hatch from the need to come to terms with his own same-sex feelings and inclinations.

All of this is drawn out in minute, almost numbing, detail by Delany. I doubt I’ve ever read anything that goes into such intimate details about someone’s sex life before. Yet Brooke and his pals invite this kind of inquiry precisely by being so cavalier about sexuality and morals. They wrote long, extremely frank letters to one another, many of which seem intended for posterity. In the end, the picture that emerges of Brooke is of a man deeply conflicted about sexuality in general: women were either virgins or whores; and the moment of sexual consummation with anyone seemed to render that person dirty forever after. That Brooke had homosexual tendencies also seems fairly well established, but—as always for Brooke—he felt vaguely ashamed of those feelings. His “Fatal Glamour” in Delany’s formulation may have been that he was more willing to die than to try to come to terms with these conflicted feelings.

Nearly as much in dispute as the question of Brooke’s sexuality is that of his reputation as a poet, which has waxed and waned over the years. Soon after his death, cultivated by ardent admirers and lovers from afar, such as Eddie Marsh, Brooke was proclaimed to be poetry’s golden prodigy, mowed down before his prime. But it didn’t take long for others to dismiss him as an overpraised pretty boy whose reputation has been vastly overblown. The truth, of course, lies somewhere in between. Brooke’s verse can be very fine; his first published work has a lovely Edwardian charm and effortlessness about it, and largely conforms to people’s notions of what poetry should be. It’s very memorable and quotable and accessible. But it can also be overly sentimental, sophomoric, and even nasty. Brooke’s most celebrated poem is 1914’s “The Soldier,” which includes the lines: “If I should die, think only this of me:/ That there’s some corner of a foreign field/ That is for ever England.” Whether one considers this sublime heroism or jingoistic claptrap, it’s so emblematic of its time as to be unavoidable in any study of the literature of World War I.

What’s ironic is that—try as he might to separate himself from England’s traditional morality and values—Brooke wound up sacrificing himself for them. Indeed, precisely because of poems like “The Soldier,” he was consciously made their poster child. That, in the end, may be the cruelest irony of all.

Dale W. Boyer is a writer living and working in Chicago.