The Next Loves

The Next Loves

by Stéphane Bouquet. Translated by Lindsay Turner

Nightboat Books. 114 pages, $16.95

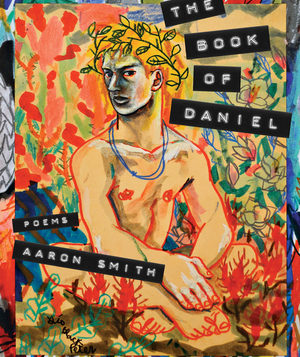

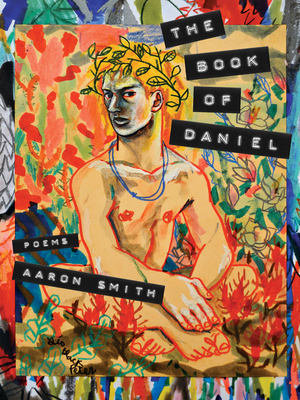

The Book of Daniel

The Book of Daniel

by Aaron Smith

University of Pittsburgh Press. 108 pages, $17.

TWO remarkable new books of poems have just appeared by two poets with very different world views. Taken together, they show—not only in their range and variety, but also in the depth of their frankness—just how far gay poetry has come. If gay desire was once timid, coded, or apologetic, it is now explicit and matter-of-fact.

Stéphane Bouquet’s The Next Loves is the more traditionally literary of the two. Bouquet writes poems of longing and the unattainability of love with titles like “Solitude Week 16” and lines like these: “I don’t know how to pronounce the l of difference between/ word and world”; and “He’s in his study-library because: where else?” It is highly literary poetry that proceeds by gaps and erasures. Bouquet is forever looking for that next face to be enraptured by: “the same one we’ve been telling ourselves/ forever in the metro someone raises/ his head.” Constantly looking for a lasting love but never finding it, he instead ensconces himself in the classics, living a life of the mind while at the same time trying to hammer out concrete details about the actual world via his written words. Several of the poems in The Next Loves rather quaintly and amusingly name the person he’s feeling so rhapsodic about: “O Eric/ Ress French—/ American swimmer scion of Indiana’s campuses.” I’m not certain what to make of that idiosyncrasy, ultimately, but it’s certainly specific. If there’s a jewel in this collection, it is undoubtedly “Light of the Fig.” A chronicle and homage to how difficult it is to be gay, it’s also a powerful elegy to all those young gay people who are no longer with us for one reason or another. Aaron Smith is not exactly at the other end of the spectrum, but his work is far more flippant, colloquial, and funny. For example, the title poem, “The Book of Daniel,” refers not to the Bible but to the actor Daniel Craig, with whom the poet is apparently obsessed. Smith’s poems can be very risible indeed: “Buck Rogers made me gay when he was stripped/ to the waist and forced to walk a runway.” He can be cheeky: “Elizabeth Bishop is like Meryl Streep—/ you have to say she’s the best whether you believe it or not.” Or darkly humorous: “I’ve written three books few people read/ and wanted to kill myself.” Sometimes all of these qualities are present at the same time. His poems have a tossed-off feeling that often reveals a more complex interior. A prime example is “Poetry Can Save the World!” which reads, in its entirety: “and I knew/ this bitch/ didn’t live/ in the same/ world as me.” An even bigger difficulty than being gay, apparently, is being Smith, as when the poet reflects: “why was I so angry when I lived here?/ Part of it was chemical, part of it was because/ I’d rather go to the shame parade/ than Pride.” On the evidence of this volume and his earlier, equally impressive Primer, Smith would undoubtedly have some interesting things to say about either parade.

Dale Boyer’s new children’s book, Justin and the Magic Stone,has recently been published.