WAY BACK IN THE 1990s, when James Berg and I began thinking about compiling a book on the life and legacy of Christopher Isherwood, we realized that we had to include Don Bachardy’s story, as the two really were and are fully intertwined. So a section of our first book, The Isherwood Century, is called “Artist and Companion.” Now Michael Schreiber has produced a comprehensive interview-based biography of Bachardy, who is 91 years old, titled Don Bachardy: An Artist’s Life (Citadel Press).

WAY BACK IN THE 1990s, when James Berg and I began thinking about compiling a book on the life and legacy of Christopher Isherwood, we realized that we had to include Don Bachardy’s story, as the two really were and are fully intertwined. So a section of our first book, The Isherwood Century, is called “Artist and Companion.” Now Michael Schreiber has produced a comprehensive interview-based biography of Bachardy, who is 91 years old, titled Don Bachardy: An Artist’s Life (Citadel Press).

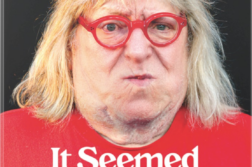

Bachardy met Isherwood at the beach in Santa Monica, California, in the early 1950s. His life, from growing up in suburban Los Angeles in the classic Hollywood era to becoming a world-renowned portrait artist in his own right, is one of the unlikeliest stories imaginable. And yet it happened, and now it is told, in intimate detail, in Don’s own words. After reading the book, I corresponded with Schreiber to get his take on this significant story and how it came into being.

Chris Freeman: How did you get the idea to do a project with Don Bachardy?

Michael Schreiber: I first arrived on Don’s doorstep about a dozen years ago merely as the friend of an old acquaintance of his, the fellow artist Bernard Perlin, who had encouraged me to “look up Donny” when I was visiting Los Angeles. Don was gracious enough to receive me. While I had some art-related questions for him at that first meeting, what forged our friendship was discovering that we’re both passionate fans of the Golden Age of Hollywood. As our conversations about art and movies and Don’s extraordinary life continued by phone and during my frequent trips to L.A., this oral history project began to grow organically. What has ultimately emerged with this book is, fittingly, a portrait of Don Bachardy, taken from his later life—or, rather, three intertwined portraits of his identities as a lifelong movie fan, as Christopher Isherwood’s legendary partner, and as an acclaimed portrait artist.

CF: Who is your target audience, and how much do they need to know about Isherwood and Bachardy to get into it?

MS: Certainly a wide swath of the older gay generation is at least somewhat familiar with Isherwood’s work and his and Don’s fabled love story. But I don’t presume that younger readers across the lgbtq+ spectrum are aware of just how trailblazing a couple they were, or what an extraordinary figure Don is as an artist in his own right. My hope is that this book finds its way into their hands, and into those of other-identifying readers as well. The many Hollywood tales in the book are certainly its enticing sugar coating, but sweeter still is the tremendous love story it tells. Although some of this story has already been well-documented, my book presents Don’s fresh, late-in-life perspectives on it all, along with a lot of previously untold material about his own life before and since the advent of Isherwood in it.

CF: Don describes himself in one of your conversations as “an artist of personality.” What can you say about this concept? Is that perhaps some aspect of his approach that really distinguishes his work and his legacy?

MS: It absolutely is. Don stands uniquely apart as an artist for having committed the entirety of his seven-decade career to portraiture and, in particular, to working only from life. He’s been insatiable in his pursuit of portraying the tremendous variety of humanity, drawing and painting people of diverse racial, gender, sexual, and generational identities—so much so that, to date, he’s created a staggering 15,000 portraits of people from all walks of life. The occasional famous face in the mix has been a professional necessity, as he explains, because how can any casual observer of his work know that he can truly get a good likeness if they can’t instantly recognize some of his subjects? But no matter how famous the faces are, his portraits are uncanny, not only for how accurately they capture a subject’s physical likeness, but also a palpable sense of that person’s personality, of their energetic presence. Don believes that that quality of animation can only be achieved from working with a live sitter and completing a portrait in a single intensive session.

CF: My experience of sitting for Don, which I have done many times, is that he resists looking at you when you show up. He basically stares at the floor, I believe to stop himself from beginning to work. He is that obsessed with spontaneity and painting from life, in the moment. Do you think that’s an accurate description of his process?

MS: That’s been my experience as well. His work is fueled by a sense of spontaneity and immediacy, of capturing the encounter with a living subject right there in the energy of the moment shared between artist and sitter. It’s why Don refuses to work from photographs of his subjects because that would remove him from the excitement of looking intently and closely at the real three-dimensional person, and of tapping into the energy of their interaction in real time.

CF: “Life” and “live” are central to Bachardy, as is his self-described “ruthlessness,” which comes across in some of his conversations with you about working with Bette Davis, for example. He seems defined by notions of confrontation, and sometimes there is almost an adversarial dynamic, especially in the last drawings of Chris, during the final stages of his illness in early 1986. What can you say about that, and do you agree with my characterization?

MS: I do. It could be argued that this harkens back to Don’s formative years as a fervent movie fan. He speaks of becoming enraptured as a young boy by the giant closeups of faces he saw on movie screens, and then of daringly sneaking into Hollywood movie premieres as a teenager (usually with his older brother Ted) to get even closer to the movie stars he revered. But it wasn’t satisfying enough for him just to see those people in the flesh. He was also compelled to confront them, and to capture those encounters in a snapshot and an autograph. It all seems a progression to the way he has since orchestrated his portrait sittings, in that he seeks to record his human subject during one live encounter—and afterwards he even asks his sitter to autograph their portrait. For Don, his sitter’s signature is essential proof both of their collaboration and that the portrait was created from life.

But since the very beginning of his professional career, Don has also committed himself to absolute truth in his work. He won’t refrain from including everything in a portrait that he can see in a sitter’s face, even though it might prove troubling for the sitter. It’s all nonjudgmental and objective observation on Don’s part, but it does establish a tension in every portrait session he does, given that his intent is never to please his sitter by somehow “retouching” them, and that he’ll be showing them their portrait immediately after its completion to have them sign it. This extends even to the many celebrities who have sat for him over the years. And, yes, those “last drawings” he made of Christopher Isherwood are especially raw in their honesty.

CF: At the beginning of chapter ten, Don refers to the “inevitability” of him and Chris finding each other. Can you say more about that?

MS: Isherwood described their meeting as having “the strange sense of a fated, mutual discovery,” and Don likewise believes their coming together was somehow predestined. That their unlikely romantic partnership not only survived but thrived both domestically and co-creatively over three decades—and in spite of the thirty-year age difference—is perhaps evidence of their intertwined destinies as “soulmates.” And it’s remarkable to consider that even forty years after Isherwood’s death, their relationship is still fueling Don. It’s an incredibly moving story that will restore any cynic’s faith in the enduring power of love.

Chris Freeman is the co-editor (with James Berg) of several books on the life and work of Christopher Isherwood.