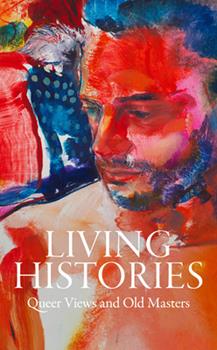

LIVING HISTORIES

LIVING HISTORIES

Queer Views and Old Masters

Edited by Aimee Ng, Xavier F. Salomon, and Stephen Truax

GILES. 112 pages, $34.95

One such experiment recently took place at New York City’s Frick Madison, temporarily housing parts of the Frick Collection—which includes Old Master paintings and other European art—while the museum’s permanent home undergoes renovation. The museum commissioned four New York-based artists to create new works during this transition. From September 2021 through September 2022, the portraits hung (one by one) in place of works out on loan.

That project, “Living Histories: Queer Views and Old Masters,” is now recapped in a book by the same name, which includes essays about the works on display and interviews with the living artists. Much of it wrestles with questions of inclusion: Whose pictures deserve to hang on a museum’s walls? Is there an institutional responsibility to represent different kinds of art and artists outside its established purview? What types of people are encouraged to walk through a museum’s front door?

The project’s curators, Aimee Ng and Xavier F. Salomon, paired each contemporary artist with an Old Master: Salman Toor with Vermeer; Doron Langberg and Jenna Gribbon with Holbein the Younger; and Toyin Ojih Odutola with Rembrandt. The coupled artworks hung in isolation on nearby walls, “in conversation.”

Doron Langberg’s Lover depicts a bare-chested man in dark underwear sitting cross-legged on a colorful couch. Wisely, Langberg has chosen to use a canvas the same size as Holbein’s Sir Thomas Moore, which immediately establishes a relationship between the two works. The pairing also benefits from its psychological tension: Moore, draped in fur and velvet, holding a folded paper in his hand, almost seems to gaze longingly at Langberg’s near-nude lover, who looks with downcast eyes at a sheaf of papers in his lap.

What am I Doing Here? I Should Ask You the Same, by Jenna Gribbon, depicts her scowling partner Mackenzie sitting on a green chair in a purple suit with a red coat draped over her shoulders, one breast flashing a fluorescent pink nipple. Holbein’s Thomas Cromwell looks bundled up and disapproving on the adjacent wall, clutching a piece of paper as if having just dashed off a complaint about her indecency. He seems to glare at Mackenzie while she gazes out at us.

Odutola’s The Listener is the only drawing in the exhibit (part of a larger series), a charcoal, pastel, and chalk sketch of an imagined queer, African, female warrior. Her muscles’ light and dark shadows mirror the folds in Rembrandt’s gown, stretched tightly against a sagging body in his late-in-life Self-Portrait.

The contemporary works’ shocks of color and flamboyance contrast with their Old Master counterparts as well as their austere surroundings at the Frick. They have youth’s fresh advantage, like showing up to a black-tie event in jeans and, rather than looking out of place, making everyone else seem overdressed. But they also feel a little random, like a classical music playlist with one TikTok-trending song thrown into the mix. Pairing paintings might create a “dialogue,” but who decides what these strange bedfellows are saying to each other?

Michael Quinn writes about books in a monthly column for the Brooklyn newspaper The Red Hook Star-Revue.