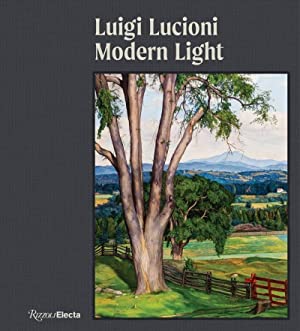

LUIGI LUCIONI

Modern Light

Shelburne Museum, Vermont

June 25–October 16, 2022

I AM NOT a great believer in fate. Still, it has a way of surprising one. Over ten years ago, while reading the letters between artist Romaine Brooks and writer Natalie Barney in Tulsa, Oklahoma, I saw a letter from Brooks mentioning that she wanted to see an exhibition of works by Italian-American artist Luigi Luciano. I had never heard of him, so I jotted down his name on an index card and promptly forgot about him. So when I heard there was a new book on Lucioni—David Brody’s Luigi Lucioni: Modern Light—I jumped at the chance to explore his work at last.

Lucioni enjoys a reputation as the “painter Laureate” of Vermont, and on the face of it, he looks like many American scene painters of the 1920s and ’30s. Picture a very different world from the one we find ourselves in now, a rural America before the Civil War. Imagine pristine mountains, upland pastures, aging barns, silos, and an occasional church spire. Communities are tidy, neat, predictable, and secure in their routines.

Lucioni may have modestly called himself a New England painter, but he was so much more than that. His queer network included the New York circle that revolved around the trio of Monroe Wheeler, who served in various influential positions at the Museum of Modern Art; novelist Glenway Wescott; and photographer George Platt Lynes. His intimates included the very talented “PaJaMa” group comprised of Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret French. Lincoln Kirstein was married to Cadmus’ sister Fidelma and supportive of their performative endeavors. This troika staged and photographed evocative nude and seminude tableaus that appear frozen in time.

An unidentified photograph shows Nancy Walter, Luigi Lucioni, Fidelma Cadmus, and Paul Cadmus acting in “Skit” at the Tiffany Foundation in Oyster Bay, NY, in 1926. Lucioni never displayed his sexuality publicly, but his portrait of Jerry (French) was given to Paul Cadmus (they were lovers) and speaks to the intimacy among these three artists. Kirstein admired and promoted Lucioni’s cool, detached magic realism because his allegories stepped out of the closet. His landscapes are subtle, unlike his gay portraits, reminiscent of Romaine Brooks’ Spring (a lesbian parable painted 1910-13). The associations that punctuate these visual images also inform the subtle works of Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Grant Wood.

Readers of James Saslow’s Pictures and Passions (1999) will recognize some of Lucioni’s homoerotic symbolism, which are also present in Demuth’s rising towers and silos, Hartley’s ardent male lovers and rising mountain peaks, O’Keeffe’s voluptuous fleshy mountains and gigantic flowers, and Woods’ ripe, swelling fields and rolling meadows—visions of youth and beauty. Lucioni was one of the gay artists of his generation who were unmoored in a sea of change. His work, mainly his portraits (though he did not consider himself a portraitist), are among the most electrically charged portrayals of gay men in modern art history.

I now understand why Romaine Brooks was interested in Lucioni’s work. Upon closely examining their queer gaze through reading Brody’s book, I recognize their shared twilight vision as a response to the heterosexism of the times. Nonetheless, emerging Modernism provided a relatively safe space in bohemia for Lucioni and others to create their vibrant gay art. Among his best portraits are of artists and lovers Paul Cadmus and Jared French; photographer Carl Van Vechten; and Ethel Waters, the bisexual singer and actress.

Luigi Lucioni: Modern Light is a beautifully produced book that any art collector would proudly display. Somewhat unfortunately, the book is being marketed by Rizzoli Electa’s publicity team as just another art book without reference to its special interest to LGBT readers or its importance to LGBT art history and culture. It belongs to a growing library of books that underscore the many contribution that gay artists have made to society and culture.

Cassandra Langer, a writer based in New York City, is the author of Romaine Brooks: A Life (Wisconsin).