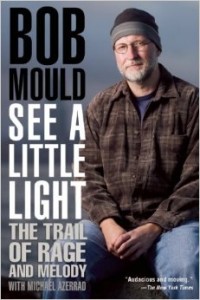

See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody

See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody

by Bob Mould, with Michael Azerrad

Little, Brown & Co. 416 pages, $24.99

IF YOU’RE LIKE ME and are occasionally presented with lists of the most influential gays and lesbians in popular music, you may have found yourself wondering: what about Bob? Best known as the lead singer of Hüsker Dü in the 80’s and Sugar in the 90’s, Bob Mould is a founding but often forgotten father of American punk rock. His first book, See a Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody, should set that record straight, as here for the first time Mould talks openly about that tumultuous trail from an insecure gay kid growing up in rural New York to a major force in alternative rock. Mould’s new memoir gives us a glimpse into the offstage agonies that made him, as he puts it, a “loud emotional person” and a “screaming hulk on stage.”

Proving that he’s still a productive collaborator, Mould enlisted the very best as a coauthor, namely journalist Michael Azerrad, whose Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981-1991 (2001) remains one of the finest chronicles of indie-rock to date. There Azerrad characterized Mould and band-mates Greg Norton and Grant Hart as follows: “The Hüskers had gotten cast as a hardcore band when what they were really doing was playing folk rock played at light speed, encased in an almost palpable cloak of swarming electronic distortion, car accident drumming, and extreme volume.”

It’s an apt description of a band that produced not so much songs as missiles. Mould likens his lyrics to “snowballs or fastballs, spitting on them, and throwing these words at the listener.” Albums like Zen Arcade and New Day Rising (composed only months apart) still grind and growl as cacophonously as they did when Mould was living his annus mirabilis of 1985. That’s the year Hüsker Dü opened for Black Flag in London, collaborated with author William S. Burroughs (who shared his love of drugs and knife-throwing), and effectively left the underground for a deal with Warner Brothers. Mould describes New Day Rising as “my drinking album,” though he swore off alcohol for good in 1986, two years before the Hüskers’ acrimonious break-up.

Since then, reinvention has been what Mould does best. Born in 1960 to working-class parents, his mother worked as a switchboard operator and his father, an abusive and paranoid alcoholic, as a TV repairman—that is, when he wasn’t secretly tape recording his family while out at the bars. For the twelve-year-old Mould, a brush with a barber’s crotch was an early indication of his sexuality: “His crotch used to touch my forearm while he was cutting my hair, and I still remember the smell of the shop. … To this day, moments like this still dictate a fair amount of my desires as a sexual being.” He goes on: “I think most gay men, like about everyone else, remember those markers, and those early experiences inform our fetishes and desires, how we lead our lives, sometimes even our professions.”

Such markers definitely shaped the career that followed. In 1978, he left his painful past behind to matriculate at Macalester College on a low-income student scholarship. Bored by schoolwork and enraged by the Young Republicans on campus and their leader, he formed Hüsker Dü after Grant Hart invited him inside the basement of his St. Paul record shop to smoke pot and play guitar. The band took its name from a popular 60’s board game (Norwegian for “Do you remember?”) in which children would outwit their parents. How punk rock is that? “The name Hüsker Dü,” writes Mould, “was an identifier, not a description … and that avoidance of conformity served us well.”

Coming out as a sexual nonconformist, however, wasn’t quite as seamless. Only recently has Mould grown into his status as a gay icon of rock music, though Spin magazine outed him way back in 1994 (the year that Sugar disbanded). For much of his book, sexuality is something of a black cloud. His college years presented the fear of being “found out by my dorm mates.” The hardcore punk scene operated under what he calls a “don’t ask, don’t tell” code of conduct. He hated “the fact that I was gay—not the act of gay sex, but the image that the media would hype up, or the one I kept in my head, of what a gay man was: queer, effeminate, camp. That was so far removed from how I perceived myself.” Yet what a difference a decade can make. After discovering Fire Island and psychotherapy, Mould likens his former self to Rip Van Winkle: “I’d been asleep for years.” The book’s last photo features Mould and current beau Michael arm-in-arm during Bear Week in Provincetown.

With this newfound confidence came new creative directions. In 2000, he was asked to play lead guitar for the film version of John Cameron Mitchell’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch. The Daily Show with Jon Stewart currently uses a cover of a Mould tune as its theme song. See a Little Light powerfully traces Mould’s private metamorphosis from an insecure pioneer half in the shadows to a fully realized music man.

It’s no secret that memoirs by famous people are only as good as the anecdotes they provide about other famous people. In this respect, Mould doesn’t disappoint. There’s R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe lusting after Mould’s boyfriend and insisting that people enter his Georgia home through a window as part of an “art project.” There’s Nirvana, knowing that Nevermind would soon put them on top of the world, trashing the stage at a rock festival in Germany. There’s Metallica traveling with their own washer–dryers, and Lenny Kravitz ordering a six-by-twelve-foot tent be built for his wardrobe.

In his own homage to Hüsker Dü, Azerrad notes that rumors circulated that Mould and Hart were secretly boyfriends, though “both men took lovers on tour and their orientation was an open secret of the indie community.” Mould tells a different tale. A self-described “long-term relationship guy,” Mould provides candid accounts of juggling a relationship and the rock star lifestyle. He describes the meltdown of his fourteen-year affair with the pot-addled Kevin, even bringing Kevin’s boyfriend into the relationship to become an official (but short-lived) “thruple.” “The ‘rock star’ trappings, groupies and such,” he recalls, “didn’t figure into my touring life. I had a boyfriend, I wasn’t looking, and on top of that, I was an unattractive homosexual.” Such self-deprecation helps to balance Mould’s sometimes boastful remarks about his influence in See a Little Light. But here, too, Mould is being modest: he sheds quite a lot of light on rock music and matters of the heart.

Colin Carman, PhD, a frequent contributor to these pages, manages a blog of film criticism at colincarman.wordpress.com