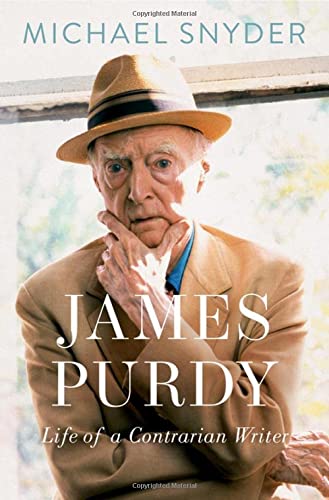

IT SEEMS to be the fate of any article discussing James Purdy to lament the lack of popular appreciation of his many novels, despite the fact that he was championed by such literary lights as Edith Sitwell, Tennessee Williams, and Gore Vidal. The latter commented on this in the obituary he wrote for The New York Times after Purdy’s passing in 2009. It almost goes without saying that the first ever biography of Purdy’s life, written by Michael Snyder, opens with a similar lament. And so too does this review of Snyder’s biography.

The narrative of Purdy as an unrecognized genius has become something of a myth in and of itself. Over the past decades, Purdy has found a niche for himself in a small but dedicated readership. His stories and poems have been treated to bibliographic editions by private presses, his novels are widely translated into other European languages, and literary scholars continue to write about his work. Still, the dominant narrative remains that Purdy never received a wide readership because he was too controversial, too ahead of his time. It is this narrative that Snyder investigates in his biography: was Purdy’s work indeed too controversial to receive mainstream popularity, or were there other factors that contributed to his slow disappearance from the literary mainstream?

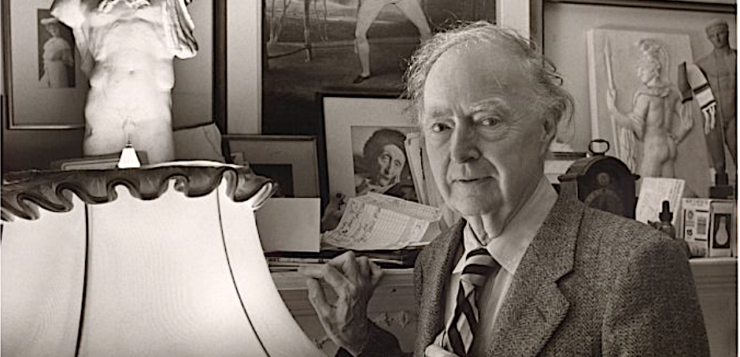

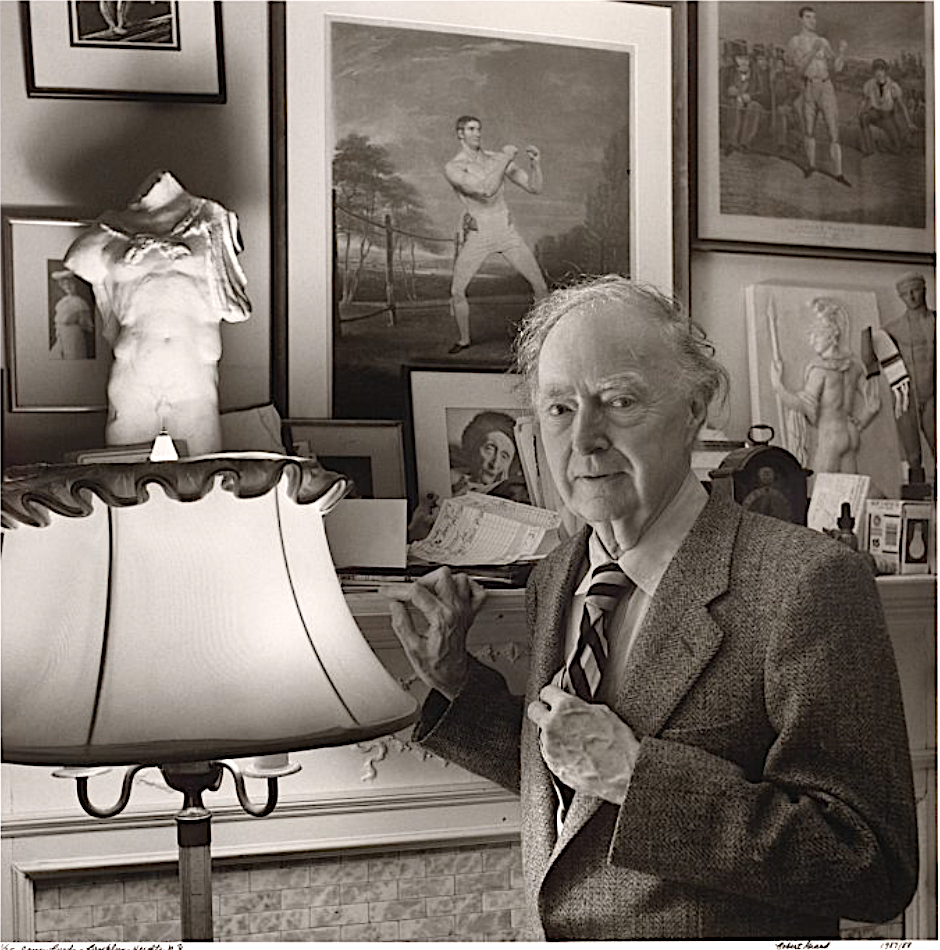

Purdy grew up in small-town Ohio and moved to Chicago in the late 1930s after finishing his studies at Bowling Green State University. In Chicago, he quickly became part of the bohemian circle around surrealist painter Gertrude Abercrombie. It is there that he started to write his first stories and developed his affinity for characters at the margins of society. Despite his talents, it took him another two decades to have his first collection of stories published. Frustrated with the constant rejection he received from magazines, he took it upon himself to privately publish his stories and first novel 63: Dream Palace in 1956. He sent these editions to authors and immediately got positive responses, most notably from Edith Sitwell. Impressed by his stories, she took it upon herself to secure Purdy a publisher in the U.K. Only after his first British collection appeared did he receive book contracts in the U.S.

Up to this point, Purdy’s biography reads like the story of a struggling author on the rise, and one would almost expect that, after this first hurdle was taken, the biography would continue to chronicle his ascent into literary stardom. The truth is quite the opposite. After enjoying some success with novels such as Malcolm (1959) and The Nephew (1960), Purdy’s opportunities to break into the mainstream were thwarted by his choice of topics for his subsequent novels. Cabot Wright Begins (1964) and Eustace Chisholm and the Works (1967) are about serial rape, abortion, and homosexuality, brought to life in “gruesome” detail. A few years before the Stonewall Riots and the first mainstreaming of gay literature, Purdy had already written in great detail about love and sexual attraction between men. The New York literary establishment simply wasn’t ready for such an honest treatment of homosexuality, and it made sure to bury his novels in negative reviews. Or, worse still, it ignored them completely.

That, at least, is Purdy’s own explanation for his declining sales and waning support from his publishers. Snyder draws a different picture, concluding somberly that Purdy himself was often to blame for his own obscurity. He was a difficult author who couldn’t accept editors infringing on his artistic vision, and he could turn on someone at any given moment. He felt he had been wronged, and he didn’t hesitate to lash out, even at people who had always been in his corner. A telling episode is when Purdy accused Robert Giroux, his editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux, of deliberately sabotaging Eustace Chisholm with a homophobic review to curb its sales and boost the career of another FSG author, Susan Sontag. These sudden and vitriolic attacks tested even his greatest champions, people like Giroux and Gordon Lish, the fiction editor of Esquire, and undoubtedly contributed to the declining support he experienced from publishers in the 1970s.

What Snyder’s biography makes abundantly clear is that Purdy is a difficult author to love. While he deserves praise for his literary genius and his pioneering of gay themes in literature, his character often gives the reader pause. He believed in the importance of his own writing and felt he was entitled to a glorious career in literature. Everyone who was standing in his way would suffer his public wrath in interviews and published letters. Particularly uncomfortable to read are the episodes in which Purdy attacks the New York literary establishment, which, according to him, was dominated by Jews who only wanted to publish Jewish, black, and female authors. His status as a white Christian male could then be the sole reason he wasn’t more widely read. Snyder somewhat uncomfortably excuses Purdy’s anti-Semitism and misogyny by pointing toward his friendly relationships with Jewish and female authors. Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that, even though Purdy’s writings are often heralded as literature that undermines social categories of race, gender, and sexuality, he was quite conscious of these categories in his private life, and all too willingly evoked them in order to demean people he considered to be enemies.

Despite these misgivings about his private life, Snyder makes a strong case for Purdy as a visionary American genius. His readings of Purdy’s novels and stories highlight the revolutionary way in which he wrote about social problems, including race, gender, and sexuality in America, particularly in the 1960s. Snyder frequently returns to Purdy’s upbringing in Ohio and interweaves references to his Native American ancestry. He provides important insights into his personal history, showing how his experiences in the Midwest influenced the idiosyncratic vernacular of his novels and the numerous eccentric characters that inhabit his stories. Through his writing, Purdy offers his readers a window on the sexual experiences of an America that remains largely hidden from view.

After reading this biography, I couldn’t shake the feeling that ultimately Purdy was indeed ahead of his time, maybe a little too much so. By the time other gay writers such as Edmund White and Larry Kramer received critical acclaim in the 1970s, Purdy had already receded into the background. Even Narrow Rooms, arguably his queer magnum opus, which was published in the same year (1978) as Andrew Holleran’s Dancer from the Dance, couldn’t revive enough interest in his writing to reestablish his reputation as a gay pioneer. Over the years, several attempts have been made to (re)introduce Purdy’s work to the general public, most notably the publication of The Complete Short Stories of James Purdy in 2013. Each time, these attempts have not amounted to very much. It is my sincere wish that the publication of Snyder’s biography will generate some sustained interest in his work, which, even after years of neglect, still manages to excite, shock, and inspire.

Looi van Kessel, who wrote his doctoral thesis on Purdy, is an assistant professor of Literary Studies at Leiden University in the Netherlands.