I

IN 1988, a headline ran in the UK news: “Beeb Man Sits on Lesbian.” I was four years old and living in a small house on a dead-end road in North Yorkshire with my parents and younger brother, one year away from starting school. The comedic headline referred to a gutsy, brilliant piece of direct action in which a group of dykes infiltrated the BBC building and chained themselves to news desks to protest Section 28, which prohibited the “promotion” of homosexuality. During the 6 o’clock news on 23 May 1988, broadcasters Sue Lawley and Nicholas Witchell were interrupted by protesters padlocked to their desks shouting “Stop the Clause” and “Stop Section 28.” I have no idea whether my parents saw this, or whether they had any idea about the protests happening in London.

But Section 28 went into effect in Thatcher’s Britain in May 1988, and it lasted fifteen years—ending the year after I finished my A-Level Exams, when I left my small Yorkshire town for a bigger Yorkshire city. My entire school life was spent under Section 28, which might go some way toward explaining why I had no idea that there were gangs of dykes chaining themselves to news desks, starting up S/M clubs, protesting nuclear weapons, fucking each other in public, or playing in bands. Section 28 was so effective that I, a closeted adolescent dyke, didn’t even know it existed until it was over.

II

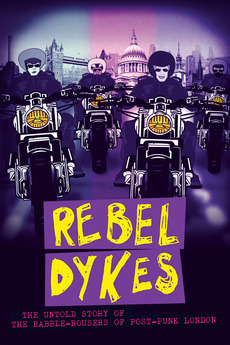

I had a visceral reaction to Rebel Dykes, a long-awaited documentary directed by Harri Shanahan and Sîan Williams about a group of punk dykes in 1980s London. I think about how different my life, and the lives of many queer people my age, might have been different if we’d had ready access to this recent history as teens, to the fact that rebel dykes existed in a tangible sense.

When I first moved to London in 2008, I started reading Jaime Hernandez’ Love & Rockets comics and fell in love with Hopey Glass, a riotous, openly queer punk with excellent hair and a love of leather boots and booze. After spending time with lesbians that I liked very much but felt apart from, Hopey was the closest I had come to being able to define my sexuality, my gender, my restlessness. Like Hopey, I wanted to be drunk constantly, to watch bands, to stay up all night having sex. I wanted to have Hopey’s unwavering confidence. The fact she was created by a cisgender straight man did not escape me, but Hopey was a real lifesaver for me in so many ways. Years later, watching Rebel Dykes, here were our own homegrown versions of Hopey: same clothes, same haircuts, same radical (mis)behaviors.

III

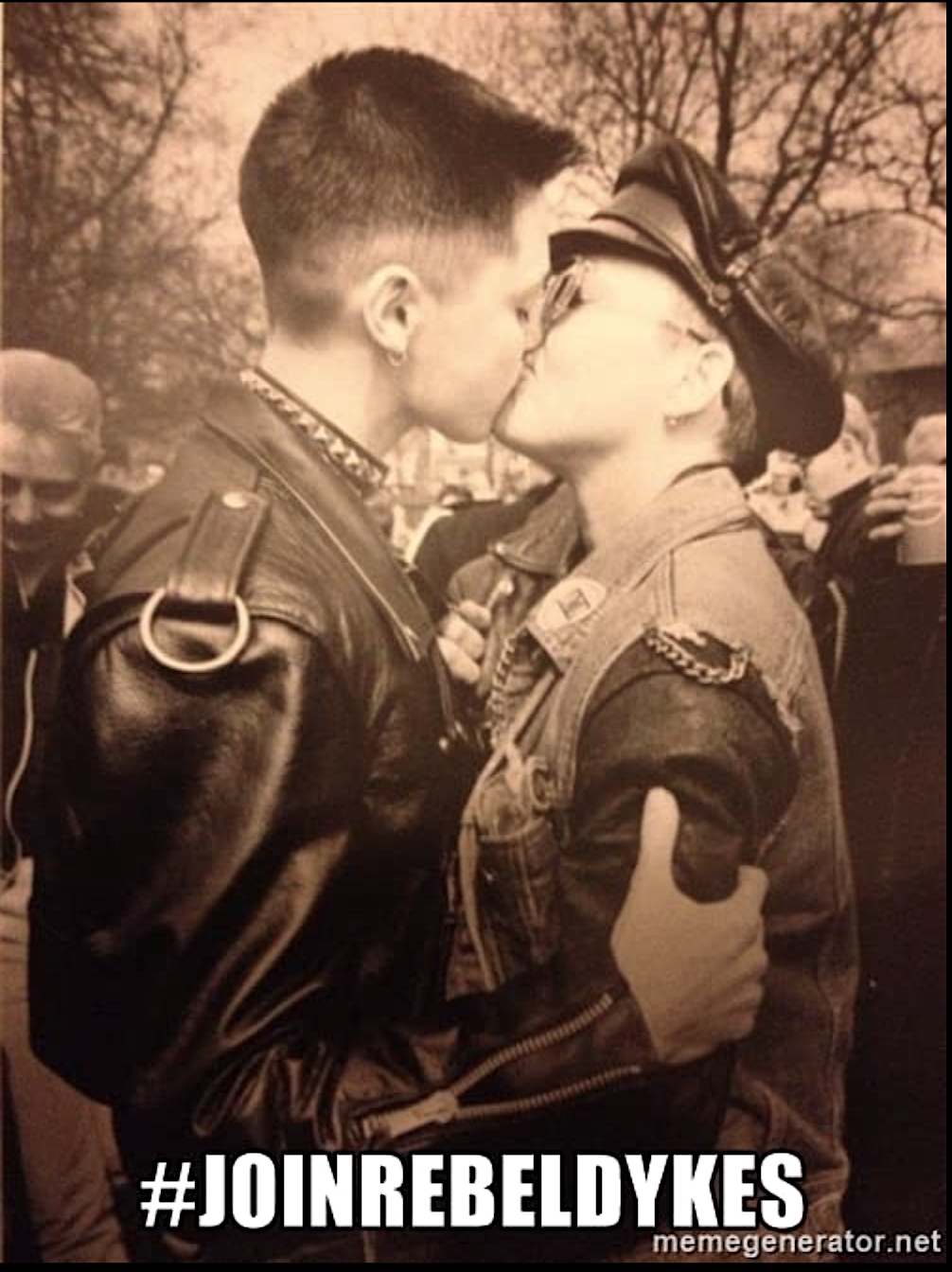

Rebel Dykes has been years in the making; I saw a preview at BFI Flare, London’s LGBT film festival, in 2016. The energy at the screening was wild and beautiful, and it was joyful to be there among so many older dykes, still wearing leather, still as unruly as ever. The atmosphere was electric: it was the same comfortable anarchy that pervades the documentary. You may look at a gang of dykes in leather and see trouble; I look at a gang of dykes in leather and see safety.

I mention the screening because Rebel Dykes is a film about togetherness, about chosen family. It follows a group of lesbians who meet at the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in the early 1980s. Someone should make a spinoff film about Greenham, which consisted of a number of different camps of women and seems like the best lesbian party of all time. There was a camp for musicians, a camp for separatists, a camp for punks. Little dykes were spending weekends at Greenham and then going home Sunday night for school on Monday. There was witchy sex in misty woodland. There was a lot of drinking and mischief. From this environment evolved queer family in the form of rebel dykes, a subculture rallying against Thatcherism, homophobia, racism, gender inequality, misogyny, and warfare—and having a lot of anarchic fun doing it.

Watching the preview surrounded by the dykes that were part of it, I could see how close they’ve remained, how they’re still family despite having gone their separate ways. Thinking about that screening now after another lengthy Covid lockdown gives me a little gut twist. So many of us have been separated from our queer families for so long now, having gone through not only a pandemic but the spectacle of virulent transphobia, institutional racism, sexual violence, abuse of police power. We’ve watched this horror unfold from screens in our individual homes, the most vulnerable among us unable to join protests, which (when they happen) are broken up with violence. We’re not able to come together in pubs or kitchens or clubs as we did before, to decompress and find comfort in one another. It’s strange watching a film so much about togetherness, when togetherness feels so alien.

IV

I moved to London in 2007, a few years before all the bars started shutting down. I got here in time for the last gasps of the Joiners, the George and Dragon, the Nelson’s Head, First Out, Glass Bar, and Trash Palace. I was working as a bookseller in Foyles by day and drinking pints in gay pubs by night, and it was about the happiest I’ve ever been.

I am constantly lamenting the death of queer spaces in London. In my imagination, there was a bar on every corner in the 1980s and ’90s, so I was surprised to hear Debbie Smith appear on screen near the beginning of the film and say there weren’t many places for lesbians to go back then. In Rebel Dykes, there wasn’t enough footage for a feature-length documentary, so Shanahan and Williams filled the gaps with punky, sketchy animations. One of the parts that plays in my head is an animated Debbie Smith walking past an animated council block with a guitar slung over her shoulder and the voiceover: “It was a great time, and a terrible time, to be young and queer in London.” It’s a perfect sound bite for the film, for the evolution of a subculture that sprang from this fortress of dykes built against the horrors of mainstream society. Another great sound bite: “We were a community because there were so many laws written against us.”

When Fisch appears on screen, then a rebel dyke, now a drag king, she talks about arriving in London and feeling isolated, feeling like the only lesbian in the city. There was a phone line, the Lesbian Line, that you could call to find out where the dyke bars were. At that time there was Gateways, a butch-femme bar, and the Kenric Society, which Debbie Smith describes as a place for rich lesbians in West London. The rebel dykes were young, punk, poor, and working-class. Some were Black, some were trans. They existed outside the realm of mainstream gay and lesbian culture, from which they felt ostracized. London was dirtier and more dangerous then, and it was harder to get around. Throughout the film, the dykes talk about waiting until dark to go out, about being constantly at risk of being bashed.

It’s easy to see how the rebel dykes came out of this climate to form a culture of incendiary, recalcitrant, gender-nonconforming queers who were determined to carve out their own place in London. They squatted in buildings in Brixton, took what they needed, slept with each other, made art, got high, formed motorcycle gangs, started bands, kept pets. As Baya, a dyke who came to London from West Berlin, says at one point in the film: “It was our own little fantasy world.”

I’ve always loved the idea of queer people making space for themselves in a city and culture that wants to reject them, both culturally and physically. The rebel dykes made London’s streets, empty buildings, and dark underpasses their own playground. Watching the film brought to mind Michelle Tea’s phenomenal essay “HAGS in Your Face,” about a similarly anarchic group of butch dykes in 1990s San Francisco who called themselves HAGS, who engaged in petty crime and rode motorcycles dressed in leather. In an interview with Dazed, Tea writes: “They represented something to me when I moved to San Francisco, they solidified that this was the place, that it was a city that could hold these beautiful raw ruffians that were living outside of the law, a rational response to a culture that hated queer people, women, gender-variant people, poor people.”

The HAGS and rebel dykes occupy a similar space in my imagination. Being queer in London, I’ve met a few of the rebel dykes in person, either through my partner or at clubs, screenings, or book events. Some are still in London filling the same queer spaces, despite those spaces looking different now. I wonder if there are still HAGS riding around San Francisco. Their story had a tragic ending; many died from bad heroin. From our present perspective, it’s a privilege and a thrill to have accounts of those who came before us. The energy you get from watching Rebel Dykes or reading “HAGS in Your Face” is the same: complete awe, total infatuation, a desire to carry some of what they stood for into our queer futures.

V

The thing I enjoyed most about Rebel Dykes was how horny it is. Here was a group of hot, androgynous young women who all fancied each other and who wanted to be fucking all of the time. We need more of this. So much attention is paid to the sexuality of gay men but very little to that of dykes, or to that of trans people.

Chain Reaction was a club night that began in 1987 at the long-gone Market Tavern in Vauxhall. It was started by rebel dykes, led by a woman called Seija, who had run a club in Finland that was a mixture of art, porn, and S/M. Chain Reaction was by all accounts an S/M dyke club, with cabaret, live sex, mud wrestling, leather, chains, and whips. Unlike a lot of lesbian spaces, it was trans-inclusive, and it looks like it was just plain fun and completely playful—a group of leather-wearing young dykes wrestling in spaghetti hoops, tying each other up, and having sex. In the film, a rebel dyke known then as “Jane, Queen of Pain” spoke about how she was ashamed of wanting sex all the time until she found Chain Reaction, through which she learned to own and explore her sexuality. She speaks about it being a safe place to get it on, about how the S/M element for her was cathartic, a way of taking the power away from the violence of the straight world: “Somehow we felt much more like we could survive a beating.”

Chain Reaction was stormed by a group of people in balaclavas with crowbars, axes, and sticks. They smashed glasses, hit dykes, and trashed the bar. They turned out to be feminists protesting violence against women by enacting violence against women. Debbie Smith calls them wavaw—Women against Violence against Women. Someone else calls them Lesbians Against Sadomasochism. They were a group of outraged feminists who thought Chain Reaction was misogynist and anti-feminist, that it was mirroring domestic abuse.

The whole affair sparked a culture war with sex-positive rebel dykes on one side and lesbian feminists on the other. The rhetoric of these feminist groups so closely mirrors that used by today’s TERFs—Trans-exclusionary radical feminists—that it’s hard not to wonder whether these are the same people. Maybe they are; Siobhan Fahey, the film’s producer, was one of the rebel dykes at Chain Reaction and says in an interview with Vice: “They were really extreme and really annoying. I think, in a way, they became what you call TERFs today. The philosophers they based their ideas on were some of the same people, like Sheila Jeffreys and, later, Julie Bindel. Trans women are the enemy now, but we were the enemy then.” The Chain Reaction debacle feels particularly prescient, born from the same rift within feminism that we’re battling today, only now we have the Internet, and we have Twitter, and there are hundreds of different methods of attack.

VI

I co-run Cipher Press, which publishes queer and trans books, and with my publisher’s hat on I am very into the ways information has been printed and distributed to the queer community over time, and in the ways queer publications have been archived. Rebel Dykes is a documentary about dykes in the 80s, a decade when booksellers were fearful of the Obscene Publications Act. In 1984, the bookstore Gay’s the Word was raided as part of Operation Tiger by the police, and customs seized over 2,000 imported books they deemed “obscene.” Four years later, Section 28 was signed into law. As far as the straight world was concerned, Chain Reaction and the rebel dykes were about as obscene as it gets.

But their experiences were documented, most notably in the photography collection Love Bites, by photographer Del LaGrace Volcano, who says: “Rather than bring my camera into the club, a sacred and profane space, we often went out into the world and created public spectacles of ourselves … we posed and performed for each other. … I think it gave us all a sense of satisfaction to see the looks on some faces when confronted by two dozen dykes in leather looking fierce and fabulous.” Although some mainstream bookshops did stock Love Bites, heavily shrink-wrapped, queer bookshops like Silver Moon and Gay’s the Word did not. They feared it would make them susceptible to prosecution. A happy addition to Rebel Dykes was an appearance from the wonderful Jim McSweeney, bookshop manager at Gay’s the Word. Back then, stocking a book like Love Bites would perhaps have made an already vulnerable queer space even more so.

Rebel Dykes also pays homage to Quim, a magazine “for dykes of all sexual persuasions.” Quim was a sex-positive lesbian magazine that ran for six years between 1989 and 1995 and followed the U.S. women’s erotic magazine On Our Backs. Quim was publishing as the rebel dykes were starting to separate, many of them leaving London, tired of the partying and/or the constant fights within feminism. We can think of it as an archive of the rebel dykes’ legacy, a continuing document of a culture they helped create.

If we want to look at queer erotica now, we can open Google or Instagram, but publications like Love Bites and Quim linked queer people living outside the world of the rebel dykes to their own sexualities and were vital lifelines for anyone who didn’t sit comfortably inside the lesbian and gay mainstream.

VII

Toward the late ’80s, the rebel dykes were fighting AIDS with ACT UP and protesting Section 28 by rappelling into parliament and chaining themselves to news desks. Rebel Dykes is the archive of a constant, endless narrative of necessary fights. It’s about the resilience and playfulness of a group of women who felt ostracized from both the straight world and the mainstream gay and lesbian world.

Watching Rebel Dykes, you can’t help but draw comparisons to the queer landscape we know now, examining what we’re still clinging to from that time and what we’ve forgotten or thrown away, and what we’ve lost. Post-Internet, it’s a very different world, with very different forms of access and acceptance. Although there are still pockets of queer family all over, how effective are these family structures in creating spaces for outsiders and rebels, when the mainstream is constantly trying to swallow so much of our queer culture? As Lisa Power says towards the end of the documentary: “We’ve gone so far into the mainstream now that we’re losing all our sharp edges.”

Are we losing our ability to be rebels? It wouldn’t be entirely fair to say Yes. Organizations like the Outside Project and Queer House Party are doing incredible work in keeping our community connected and campaigning, and the direct action group Sisters Uncut are bringing queer and trans people together through their activism. However, whether because of the “new normal” evolving from the pandemic or the fact that so much of our lives is now lived online, we’re adjusting to new types of togetherness, new ways of protest, different structures for our chosen family and communities—and it feels like a very different world. Perhaps it’s a lack of the playfulness that comes with taking up, and taking over, a physical space, of using our queer bodies to create mischief, fill rooms, and crowd public spaces.

The rebel dykes laid the foundations for so much of today’s queer culture. After rebel dykes came the Lesbian Avengers in the ’90s, then Riot Grrrl, Queercore music, and Queer Mutiny. It’s thanks to them that we can be a part of a queer culture that fits us. After growing up under Section 28, it’s a privilege to have access to this film, and I tip my (leather) cap to the filmmakers for creating such a playful, wild, sexy, and important documentary.

This essay first appeared online to mark the 2021 BFI Flare premiere of Rebel Dykes. It is part of Culture Club, a community publishing venture from the queer feminist film curation collective Club des Femmes.