THE ROOM IS DARK, though not empty. In the dim glow of red candlelight, figures gather around ritualized scenes, bondage and impact, submission and care. A domme’s voice speaks with a low and steady tone, breaking the respectful silence, leading with the invocation: “Breathe with me.”

The room becomes silent again. The subtle sounds made by shifting bodies and settling leather stops. What follows is a uniform, shared respiration, the inhale and exhale of some 23 people of various genders: leather-clad butches, elegant femmes, nonbinary figures beautified with rope and steel. Their faces are fixed in one direction, a central scene where a figure is carefully and artistically tied up in a complex pattern created with ropes—a practice known as shibari. The figure begins to sway slightly in unison with the rhythm. The domme places a steadying hand on their shoulder, a touch both firm and reverent, as the first strike falls on their bodies—not hurting, but with the solemn resonance of a bell.

Beginning with the rise of institutional Christianity, later intensified under colonial modernity, Western regimes have used every conceivable means to create a separation between sexuality and spirituality, labeling queer desire both sinful and scandalous. This forced belief system has generated profound shame, reducing true erotic expression to the margins of accepted life. Yet in spaces like this dungeon, a thriving movement is trying to change that.

Queer BDSM practitioners do not shy away from taboo; they embrace and consecrate it. In doing so, they transform sexuality into a source of healing and spiritual liberation. Rituals such as these elevate desire from being merely physical to the realm of ecstatic, embodied theology. This is a safe haven for souls cast out of churches, shamed in confessionals, or damned by doctrine. Here they confront decades of repression, turning taboos into holy acts and reshaping the relationship between spirituality and intimacy. Such queer BDSM communities craft sacred rituals that revere sexuality as a vital, spiritual force, challenging conservative notions and opening new pathways for understanding identity, power, and transcendence.

Ritual as Reclamation

The dungeon is a sacred space, a site of historical recovery, not a place of punishment and fear. It’s a site that represents reverence. The origins of this spiritual insurgency were recorded in the archives of 1970s queer and feminist resistance, faded photocopied pages of lesbian-separatist zines, and the polemical manifestos of the Samois collective. In their 1981 book Coming to Power, members of the collective wrote that exploring power and sensation wasn’t about copying the patriarchy but about dismantling it. They saw the dark room as a safe space where people could transform their trauma, take control, and experience a kind of spirituality that wasn’t about rules but about being true to their desires. Theologian Marcella Althaus-Reid later called this an “indecent theology” in which the sacred is found in the honest expression of desire, not in strict beliefs.

Groups like the Church of Tantra combined BDSM with tantric practices, seeing erotic energy as a spiritual force (kundalini) and the body as a temple. They treated the dungeon like a mystery school where people explored spirituality through power dynamics. Before enacting a BDSM “scene,” they’d carefully discuss limits, like setting a sacred intention. The “safe word” was like a powerful prayer, allowing the submissive to regain control instantly. This shows how power can be creative, not just restrictive. When people consensually explore domination and submission, they create a new reality built on trust and shared release. The body, often controlled by societal norms, becomes a source of deep, ecstatic understanding.

Impact play can be seen as a kind of meditation through physical sensation. When someone is struck repeatedly, whether with a hand, a flogger, or a paddle, the steady rhythm can help them enter a calm, trance-like state. In this state, their thoughts fade away, and they become deeply aware of their body and feelings, letting go completely. This experience is similar to the self-whipping rituals of medieval mystics, but it’s not punishment. Instead, it’s about freedom awakening the body and treating it as something sacred.

Shibari, or rope bondage, is more than just tying someone up; it’s a kind of hands-on, physical prayer. Like the beads of a rosary or the repeated chants in Sufi meditation, the rope acts as a touch-based mantra. Every knot is like a breath, and every loop of rope is like a promise. The rope becomes a sacred thread that connects two people, creating a delicate web of beauty, feeling, and trust. The person being tied isn’t trapped; they’re gently held, carefully shaped, and honored, like a living symbol in a ritual of closeness and care.

These archives demonstrate that queer BDSM didn’t create sacred eroticism from scratch. Instead, it bravely and carefully brought it back to life, reclaiming spiritual and sensual practices that were nearly wiped out by Christian colonialism. In doing so it has built a real, lived form of spiritual belief for people who need it most.

The Æsthetics of Subversion

If the rituals in the dungeon are like a worship service, then the art and visuals that come from it are its sacred texts. This is a kind of spiritual belief expressed not through words but through images and actions. It playfully and proudly flips the religious symbols once used to shame LGBT people. Queer kink artists take those old sacred signs, once tied to punishment or guilt, and strip them of their power to condemn. Instead, they fill them with hope and possibility, what scholar José Esteban Muñoz called “queer futurity”: a vision of a joyful, better future that turns tools of suffering into sources of pleasure and liberation.

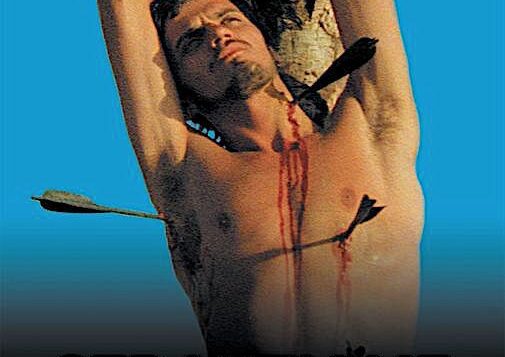

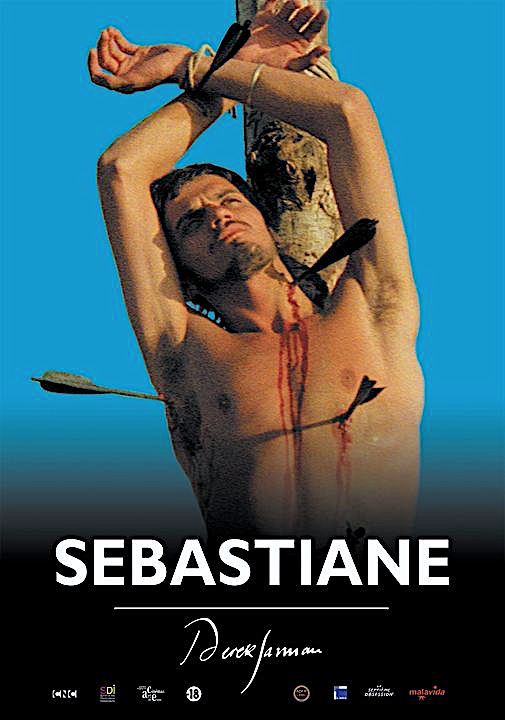

A key example of this bold visual reimagining is Derek Jarman’s 1976 film Sebastiane, which takes Saint Sebastian—a 3rd-century martyr usually depicted in Renaissance art as a beautiful young man pierced by arrows in a moment of holy suffering—and transforms his story into a sunlit, Latin-speaking celebration of gay desire. In Jarman’s version, Sebastian’s exile in the desert isn’t a punishment; it’s more like a pagan paradise. The arrows that kill him aren’t just tools of torture; they become symbols of intense, almost spiritual pleasure. The film ends with a long, quiet shot of Sebastian’s body, pierced but radiant against the sky. It doesn’t feel like a death scene; it feels like a moment of transformation both sexual and spiritual.

Here Sebastian isn’t just a helpless victim receiving God’s grace. He’s an active participant in his own sacred experience, turning martyrdom into rapture. This is the heart of the queer kink æsthetic: taking stories of pain and suffering and reclaiming them. It’s not about ignoring pain but about taking back its meaning from religious authorities and rewriting it as a journey toward strength, joy, and personal transcendence.

This idea of creating new visual saints lives on in the work of contemporary photographers like Del LaGrace Volcano. In series such as Saints and Sinners, Volcano places genderqueer, butch, and intersex people in poses and settings that echo traditional religious art, complete with halos and classical framing. But this isn’t about asking to be accepted into the old religious canon. It’s about boldly declaring a new one. As Volcano puts it: “If you can’t find a saint who looks like you, become one.”

Their subjects often look straight at the viewer with confidence and defiance, portrayed with the reverence once reserved for holy figures. The soft, glowing light that highlighted the Virgin Mary now shines on top-surgery scars or the worn leather of a harness. This is sacred storytelling for those who break gender norms, a new kind of sainthood written not in ancient texts but in scars, sweat, and steel.

Similarly, the performance artist Cassils turns the body itself into a living relic of resistance. In works like Becoming an Image, they attack a monumental clay pillar in darkness, the only illumination coming from the flash of a photographer, freezing their straining, sweat-sheened body in a visceral tableau. The performance leaves Cassils bruised and breathless, their body a testament to the physical cost of making oneself seen in a world that demands invisibility. The resulting photographs are not mere documentation; they are sacred objects, akin to the Shroud of Turin, bearing the ghostly impression of a struggle both physical and metaphysical. Cassils’ body becomes a site where anti-queer violence is not merely represented but endured, metabolized, and alchemized into a silent testament of endurance.

This visual theology isn’t confined to galleries; it is lived in the spaces where kink is practiced. It is common in queer dungeons to find small, makeshift altars, a candle flickering beneath a printed image of Marsha P. Johnson, a rosary coiled next to a pair of surgical steel clamps, a flogger draped beside a prayer card for Saint Wilgefortis (the female saint who miraculously grew a beard to escape an unwanted marriage, a perfect emblem of bodily autonomy sanctified through defiance). This syncretic spirituality, this punk-rock bricolage of relic and restraint, prayer and pleasure, is a profound act of world-building. It creates a tangible lineage, connecting the spiritual resistance of the dungeon to the political resistance of Stonewall and beyond. These altars announce that our saints are here, our rituals are valid, our tools of pleasure are also our tools of consecration.

In repurposing the crucifix, the halo, and the altar, queer kink does not mock faith; it stages a hostile takeover of its æsthetic machinery. It argues that the sacred is not the sole property of the orthodox but instead a democratizing force that can be, and is, remade in the image of those who’ve been cast out.

Consent as Liberation Theology

The sacred space of the dungeon, with its reclaimed iconography and ritualized practices, isn’t an escape from the world but a deliberate intervention within it. If the rituals are the liturgy and the visuals are the scripture, then the unwavering commitment to consent is the ethical cornerstone, the liberation theology in practice. This is where the ecstatic experience transitions from personal catharsis to political blueprint, modeling a form of relationality directly antagonistic to the coercive powers of the state and the soul-deadening demands of capitalist heteronormativity.

At its core, the BDSM principle of negotiation functions as a profound, sacralizing speech act. Before a single rope is coiled or a flogger is lifted, participants engage in a detailed dialogue about desires, limits, and triggers. This conversation is the antithesis of the assumed, nonconsensual power dynamics that structure our daily lives, from the patriarchal family to the exploitative workplace. In the dungeon, power is not imposed; it is invited, discussed, and meticulously bounded. This pre-scene ritual enacts what theologian James H. Cone insisted: that God dwells not in the halls of power but in the struggle of the oppressed for self-determination. Here the “divine” is located in the vulnerable, truth-telling space where marginalized people articulate the terms of their own embodiment, transforming their historical position as objects of control into subjects of their own sacred drama.

The safe word, then, becomes a profane prayer made sacred by its function. It’s a word of ultimate power, a sovereign utterance that can halt the constructed universe of the scene instantly. This is a radical, practical theology of grace, not a top-down pardon from a distant deity, but an immanent, ever-available power vested in the most vulnerable person in the dynamic. The submissive, who may outwardly embody powerlessness, holds this ultimate veto. This inverts the traditional Christian paradigm of redemptive suffering. Here suffering (or its simulation) is not a passive, endured path to holiness but an active, consensual, and revocable journey toward ecstasy and self-knowledge.

This model of chosen, negotiated power offers a devastating critique of the systems that govern our bodies outside the dungeon. Capitalist heteronormativity depends on naturalized hierarchy and the extraction of life without consent. It thrives on our alienation from our own sensual, ecstatic potential. The queer kink scene, by contrast, organizes itself around the principles of enthusiastic agreement, mutual pleasure, and the sacredness of individual autonomy. The ecstasy sought is not a private high but a communal testament that another world is not only possible, it is already being practiced.

Thus the intense, blissful feeling often called “sub space” for the person receiving and “dom space” for the one in charge isn’t just zoning out or escaping reality. It comes from a clear, thoughtful agreement between people, built on trust, care, and honest talk before anything even begins. This deep, uplifting feeling is like what writer Audre Lorde meant by “the erotic”—not just sexual pleasure, but a strong, positive energy that helps us to resist injustice. It’s not about running away from the world but about knowing yourself and the world better. This kind of powerful, freeing experience only happens when we truly respect each other’s humanity. In a world that often takes away queer and trans people’s control over their own bodies, choosing to give that control willingly within safe, agreed-upon limits is a bold way to take it back. This isn’t just role-playing. It’s real freedom, felt in your body.

The Urgency of Sacred Praxis

The theological and political blueprints forged in the queer dungeon were never meant to stay there. They are, by their very nature, exportable, a portable sovereignty meant to be deployed against the very systems that make such spaces necessary. In an era in which “religious freedom” is weaponized as a license to discriminate, in which states enact laws denying healthcare and services to LGBT people, the embodied theology of queer kink ceases to be a subcultural practice and becomes a vital framework for public survival and resistance. The consent literacy, the reverence for bodily autonomy, and the reclamation of ecstasy are direct counter-liturgies to the theocratic impulses seeking to legislate our bodies into silence and shame.

Consider a present-day vignette: a trans woman is turned away from an emergency room, the rope-marks from a consensual shibari scene misread by staff as signs of abuse, their “moral conscience” clause invoked to deny her care. Her body, marked by sacred trust, is criminalized by a system that sanctifies only the violence it authorizes. This is the frontier of our struggle. The same governments that invoke scripture to justify such erasures are performing a perverse liturgy of their own, one of control and ontological violence. They preach a gospel of “natural order” that pathologizes our desires and polices our genders. In stark opposition, the queer kink community offers a lived theology in which power is negotiated, identity is self-determined, and the body is revered as the ultimate site of truth. Our “religious freedom” is not a right to exclude but a right to consecrate, to name our bonds as holy, our chosen families as kin, and our desires as divine.

This is why this praxis matters now, with a fierceness that is both practical and spiritual. The skills honed in the dungeon are the very skills required to navigate and resist an increasingly hostile public sphere. These include:

1. The rigorous consent we practice is the same clarity we must demand from legislators and medical professionals.

2. The sovereignty over our bodies we enact in a scene is the same autonomy we must defend in courtrooms and at the ballot box.

3. The communal care that ensures every participant’s safety is the same mutual aid that we must extend to our most vulnerable in the face of state abandonment.

To gather in a dungeon and practice this sacred trust is to engage in a form of direct action. It is to build in the shell of the old world the foundation of the new. It is to assert with our whole bodies that we will not be shamed back into the closet or the confessional. We have written our own scripture on one another’s skin, and we are building our own altars in the shadows they cast. This is the blueprint for a world where all bodies are sacred. The dungeon door is open. The liturgy of liberation has been written. The challenge now is to breathe it into being, beyond the candlelight, for all the world to feel its resonant, defiant beat.

Umar Ibrahim Agaie is a writer and advocate exploring the intersections of mental health, neurodivergence, and queer identity.