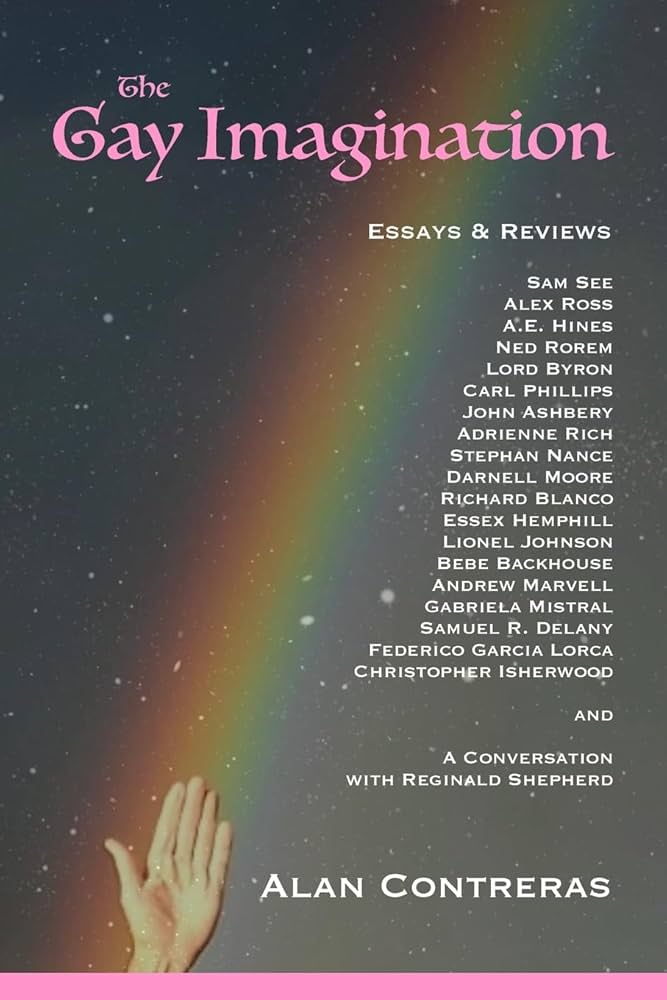

THE GAY IMAGINATION

THE GAY IMAGINATION

by Alan Contreras

Oregon Review Books. 254 pages, $25.

ALAN CONTRERAS, a regular contributor to this magazine, is the author of four books of poetry and more than a dozen works of nonfiction, principally about ornithology and higher education law. In contrast, The Gay Imagination is a collection of pieces about poetry and music, areas in which the author proves to be a sharp and knowledgeable writer. He applies a keen intelligence and a cultivated taste that reveal an impressive familiarity with a wide range of poetry.

The first half of the book includes 24 of Contreras’ essays and reviews, focused for the most part on gay writers and musicians. Among them, he tackles poets Richard Blanco, Essex Hemphill, Adrienne Rich, and Bebe Backhouse; composer Ned Rorem; and queer songwriter Stephan Nance. Some of the reviews look further back in time to the poetry of Byron, Whitman, Andrew Marvell, Federico García Lorca, and Gabriela Mistral. Contreras has a talent for nailing a poet’s style in a few words: A. E. Hines exhibits “a transcultural breadth of image”; Carl Phillips “does not use a hundred-watt word unless it is the right word and the best word in a given line.” Of Rorem, who published a host of diaries over the years, he writes: “It might be more accurate to say that his writing is likely to survive in toto as a body of literature read and discussed for years to come, despite its somewhat repetitive nature, while his music is likely to be remembered in bits and pieces, with much of it fading out over time.” As someone who has interviewed and written about Rorem, I would have to agree. Contreras’ reviews are peppered with references to dozens of other poets he knows and loves. Occasionally he parades his familiarity with these poets a bit gratuitously, and sometimes his prose reaches too far for a sense of grandeur, as when he calls Samuel R. Delaney “the Black gay ambulatory monument of the urban literary universe.” But in general Contreras has interesting and perceptive things to say, and he says them in a clear, straightforward manner. Case in point: about John Ashbery and his “glittering word-storm,” he writes: “His way of writing was a breath of energy to many poets of the last half of the 20th Century. Having felt his infused word-spray puffing into their ears, some ran to their desks, pen in hand, while others fled gibbering into the shrubbery. They all still do these same things, which speaks to the breadth of his influence.” There are many other small felicities in these essays. For example, in a piece about Gabriela Mistral, the Nobel Prize-winning Chilean poet, Contreras spends several paragraphs comparing four translations of her poem “The Foreigner.” He contrasts one translator’s apt choice of words to “the technically purer but boring” choices of another. In another review, he unabashedly praises the book cover: “How many book covers make you cry?” And in another, he pokes fun at the “outgassing bayous of critical technical English.” An especially strong entry is his “Danger of Uncontrolled Poetry,” a 2021 essay that takes to task the censoring of literary expression in an effort to maintain political correctness. “This word-burning must stop,” he writes. “Are we to become a silent society, publishing nothing that a nine-year-old Baptist might not enjoy, out of fear of causing offense? … It’s a matter of denying adult readers a full range of literary experiences in order to avoid controversy.” The second half of the book gives us Contreras’ complete email correspondence with Reginald Shepherd, a gay African-American poet who died in 2008 at age 45. “There are no pallid stones in Reginald’s lapidarium,” he writes. Shepherd “had no time for the poetry of pathological personalism, he recognized that below a certain point economy of expression becomes chastity of imagination.” These exchanges, which spanned the last seventeen months of Shepherd’s life, should prove valuable to a future biographer of the poet, whom Contreras calls “a pure shining intelligence.” What Contreras says about one book he reviewed—“there is little sense of wasted language or too much time trotting on a particular hobby-horse”—aptly applies to his own method in these essays and reviews. Self-published or not, this is a solid little anthology by a solid, workmanlike reviewer.

Philip Gambone’s latest book, Zigzag, is a collection of short stories about the lives of older gay men.