I FIRST CAME TO KNOW Edmund White through his work, of course, which was de rigueur reading for gay guys coming of age in the 1970s and ’80s. Years later, we met through social media exchanges, after which he invited me to West 22nd Street to act as a fill-in caregiver-typist-companion. Ed was recovering from a series of small strokes in 2012 and didn’t want to be left alone. His boyfriend (later husband) Michael Carroll was leaving for Chapel Hill to help his friend Phil move from there up to Boston. In Michael’s absence, I was hired to give Ed a hand with his new book manuscript, Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris. Through our correspondence, he learned that I was a French major and devoted Francophile. He and Michael got a kick out of the fact that I’d been friends with writer M. F. K. Fisher and had had dealings with Lowell native Bette Davis.

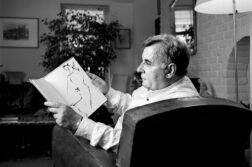

Ed’s daily regimen was this: up early, breakfast, usually consisting of cereal, strong coffee, a sweet roll, perhaps while checking his email, catching up on correspondence. This was followed by work, dictating what he’d written the night before. He wrote longhand in black ink. Right away, he asked me how a sentence or two could be improved. But this was the renowned Edmund White, and I said, “I wouldn’t presume—,” to which he purred: “Please do.” Ed had a habit of quite suddenly running the palm of his hand over his face, from forehead to chin, in one, rapid movement. Before I realized this was a nervous tic, I took it to mean he was exasperated with my work performance.

Work would wrap up around noon for lunch, usually restaurant sushi or a sandwich (always Ed’s treat). This would often be followed “for fun” by Ed giving a lecture at one or another prestigious venue around town before coming home to get ready for his guests. Ed loved to entertain; he would arrange the most delightful gatherings in the manner of what his lifelong friend, artist Marilyn Schaefer, called “dumpling evenings,” intimate get-togethers and dinners (never more than six guests). Ed had an almost psychic knack for bringing people together who would get along famously. A string of literary lights passed through that lovely room: John Rechy, Benjamin Taylor, Joyce Carol Oates, Barry McCrea, Gabe Hudson, J. D. McClatchy, Chip Kidd, Christopher Bram, Alfred Corn. Ed knew everybody. He kept a heady schedule (I had a hard time keeping up).

There was an Auntie Mame aspect to Ed’s character; in the middle of work or business, he’d be seized with an idea: “Let’s go to the theater!” “Let’s go try this new restaurant!” He’d grab his coat (he was fond of an old Miyake frock) and head us out the door. He loved squiring me and others around Manhattan and was a kid on Christmas over the latest Broadway play—he disdained musicals—or restaurant. In Ed’s company, there was never a dull moment. After a performance of Balanchine’s Jewels at Lincoln Center, we spied Peter Martins in the lobby and went over for a chat. During my work visits, we ran into Alan Cumming strolling the Garment District; Charles Blow in the men’s room at Babbo; Thomas Mallon in City Hall Park; Mark Doty, Sarah Schulman, and a rising Ocean Vuong in the East Village’s Phoenix Bar.

Ed was inordinately generous; he liked handing out wads of cash. One time, in payment for what didn’t amount to more than a morning’s work, he slipped $500 into my hand. He was possessed of a voracious appetite—for food, for people, for sex. There’s no describing what a brilliant, fertile mind he had, or what delightful company he could be. He was capable of expounding on Balzac and Proust one minute and be collapsed on the floor in laughter the next, possibly over a joke about actresses with serial husbands (like Liz Taylor and Hedy Lamarr) and what a nightmare they must have been to live with. He got a charge out of seeing how a guy my age could be so gullible, and once had me convinced that he’d composed the national anthem of Burma. When I was back home, he had the disarming habit of ringing me up, saying not “hello” but chiming excitedly “Write this down!” and would dictate an anecdote he’d remembered and wanted preserved.

Ed would retire early to his bedroom, but I don’t think he ever slept; he’d be up all night writing, listening to the radio, or reading. He read at an almost extraterrestrial speed, and one bedtime I remember he began Lanny Hammer’s thousand-page biography of James Merrill, and by morning had finished it. Ed usually played opera while he wrote; he said music facilitated his writing. Michael Carroll was the opposite, needing complete silence. When he wrote, he wore ear plugs. Both he and Ed were thoughtful hosts. Remembering that Miloš Forman’s Amadeus was one of my favorite films, Michael went out and rented it, and they ran a private screening in Ed’s bedroom. A very special Christmas Eve.

I’ve kept thousands of emails that Ed sent me through the years. Whenever I need a lift and a laugh, I pull one up and feel much better. Ed’s company, whether in person or on the page, made of life something sparkling, something special. The thought that this reservoir of creativity has left us forever is shocking.

_________________________________________________________________

Leo Racicot, a poet, essayist, and food writer, is the author of Alone in the Yard and See You Again in the Spring: Remembering M. F. K. Fisher and Her Circle of Friends.