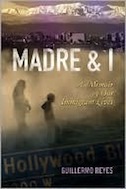

Madre and I: A Memoir of Our Immigrant Lives

Madre and I: A Memoir of Our Immigrant Lives

by Guillermo Reyes

University of Wisconsin Press. 278 pages, $18.95

GUILLERMO REYES’ Madre and I: A Memoir of Our Immigrant Lives follows the parallel lives of María, a Chilean single mother, and her gay son Guillermo, who immigrate to the United States in the 1970’s. Their American journey begins on the East Coast, in Maryland and Washington, D.C., and ends on the West Coast, in Los Angeles, where María becomes a maid to Hollywood stars. Highly intimate, mixing poignancy with humor, Reyes’ account exposes the seams that unite the political and the personal.

Two traumatic events neatly bookend the narrative: Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’état in Chile on September 11, 1973, and the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, which echoed the dreaded 9/11 date in 2001. The individual tale of the immigrant is cast against a backdrop of political events and references to popular culture, especially film. Indeed, María alludes constantly to The Sound of Music, and at one point she poses for a picture holding Charles Jaffe’s Oscar for Annie Hall in 1978, taken while working in his house. Not surprisingly, Reyes, who is a well-known playwright, filters the narrative material of his life through the prism of film, exposing the interplay between reality and fiction. Memoirs, after all, rely on a montage of selected memories. The relationship between mother and son takes center stage as the elusive paternity becomes a metaphor for their exiled condition in a sort of “fatherlandlessness.” In fact, Reyes’ immigrant status gets commingled with his sexual identity to create an intricate psychological portrait of an individual doubly exiled: at once by the American community and by the heterosexual majority. The exercise of writing a memoir thus serves as an official coming out as gay and immigrant, a feat even the more difficult given that the writer, as he explains in the memoir, suffers from BDD, body dysmporphic disorder. Individuals afflicted with BDD believe they harbor unseen flaws and go to great lengths to avoid exposure, including complete seclusion in some cases. The reader follows the difficult situations created by this disorder: the avoidance at all cost of going to the beach, the panic at undressing in front of another person, the sexual repression that ensues. Painfully, Reyes admits that “The shame would destroy me in the full blossoming of my youth. It made sense to hide.” The disorder forces him into “a downward spiral of ‘closetedness,’” torn asunder by the very act of writing this memoir. Reflecting upon a performance by Tim Miller at the Cast Theater in L.A., Reyes concludes that “I didn’t think it was possible for an artist to reveal aspects of his private life in public” and end up “naked on stage.” Taking his cues from this performance, the author stages a similar strip-tease of the soul, shedding layers of deceit and inviting the reader/voyeur to partake in his journey of self-discovery. The play between invisibility and performance lies at the heart of Reyes’ struggles, and it echoes the immigrant’s conundrum. At one point, Reyes points out that “in the aftermath of the 1965 immigrant law reform,” non-European immigrants were able to come more freely into the U.S. But after 9/11 comes the closing of the American border as immigrants come to be viewed with greater suspicion, especially in an economic climate that needs scapegoats to blame for our problems. Reyes, who teaches at Arizona State University, reflects upon this shift: “The anti-immigrant rallies have made us suspect. Even legal immigrants were bashed in the California hysteria of the 1990’s. In Arizona that issue has become even more contentious” following passage of SB1070 last April, which authorizes Arizona police to demand proof of citizenship of anyone they suspect of being in the U.S. illegally. By recounting his struggles in the U.S., Reyes drives home the point that, while our nation is built upon the sweat of the immigrants’ brow, the most recent arrivals tend to be relegated to the margins of society in the best of times, singled out and openly attacked when times get bad, when nationalist sentiments are inflamed. The “our” in the subtitle of this memoir replaces the individual story with a universal narrative, reminding us that we were all immigrants to this country at some point in the past, and that a welcoming tradition toward the other, whether recent immigrants or gay people, has always prevailed in the end. Eduardo Febles is an assistant professor in the Modern Languages Department of Simmons College.

________________________________________________________