IT’S THE FINAL HOUR of the year 1966. In Hollywood, a radio deejay sets down the needle on the number eight song of the year. “I love the colorful clothes she wears/ And the way the sunlight plays upon her hair.” A few miles away, in Silverlake, things are hopping at the Black Cat. Colored balloons cover the ceiling. Boys dance with boys, the jukebox wails, and a couple of undercover cops play pool over in the corner. Six or seven additional plainclothes officers mill around in the crowd. At 11:30, a gaggle of glittering drag queens arrives in full-blown bouffants, sequins, and wobbly spiked heels. The bartender cranks up the Supremes’ “You Can’t Hurry Love.”

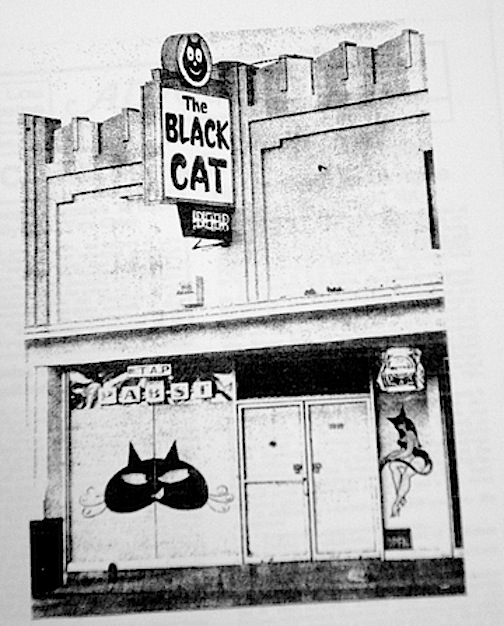

The Black Cat is one of about a dozen gay bars lining Sunset Boulevard in Silverlake, the heart of L.A.’s gay community in the 1960’s. Many are beer bars with jukeboxes, pool tables, and pinball machines, inhabiting rundown buildings where the rents were cheap.

It’s just a few minutes before midnight on New Year’s Eve at the Black Cat, and the Rhythm Queens, a trio of black women singers hired for the night, are getting ready for their big number. Suddenly, the jukebox cuts off, and for a brief moment all that can be heard is the tinkle of champagne glasses. All eyes are riveted on the clock behind the bar. Then a cheer goes up. “Happy New Year!” The Rhythm Queens take their cue, belting out a jazzy Auld Lang Syne. The bartender snips a string and the balloons cascade down onto dozens of kissing couples.

The undercover cops exchange nods. Without warning, one officer seizes a kissing customer by the shoulders. “You’re under arrest!” He pushes the man to the ground. Another cop grabs the bartender. Wine glasses shatter, Christmas decorations come crashing down. Patrons scream with fear, running for the exits. One customer reaches out to open the front door. The butt-end of a pool cue cracks down on his head. Blood spurts from his ear as it splits open. Another man is flung head-first against the jukebox.

Moments later, a dozen uniformed cops from the Los Angeles Police Department charge into the bar, batons swinging. One patron is clubbed from behind, then kneed in the groin. As he falls to the floor, his bowels empty. Two panicked customers rush out the back door, seeking refuge in the New Faces bar just across the street. A couple of plain-clothes officers follow. Just inside the New Faces, the fleeing men are tackled and thrown to the ground. Shocked, the female bar owner comes forward. “Can I see some identification?” she asks the plainclothes officers. In response, one of the cops hits her, then shoves her to the floor. A cop seizes the bartender, Robert Haas, and yanks him across the bar. Haas is struck, dragged out onto the sidewalk, and beaten so severely that his spleen ruptures. He doubles over, going unconscious on the way down.

New Year’s Day, 1967

Another sunny day in L.A. Motorized carts draped in luscious mantels of carnations, daisies, and of course roses glide up Colorado Boulevard in the Rose Parade. Millions of snow-bound Americans are glued to their TVs, watching host Pat Boone chat with Bewitched’s Elizabeth Montgomery as the floats glide beneath a cloudless sky. Over at Los Angeles County General Hospital, bartender Robert Haas is in critical condition with a ruptured spleen. At LAPD’s Parker Center, fourteen Black Cat customers have been booked for lewd behavior. Their crime? Kissing for more than three seconds.

Local businessman Alexei Romanoff is not happy. “I wasn’t at the Black Cat that night,” he said, “but within hours I heard about the raid. I was absolutely irate. I got on the phone with friends. Everybody was angry. We talked about making a plan to express our outrage.” Romanoff had once been an owner of the New Faces bar. Working as a nurse and pursuing an acting career on the side, he was also intimately involved in the gay bar scene. “In the 1950’s and 60’s, gay bar culture was a crucial part of our community. It was a place to meet new people, maybe even meet a partner,” explains Romanoff. “Police raids at gay bars were common at that time. So were beatings and arrests. It was really scary. We were so vulnerable. Kissing was a crime; cross-dressing was a crime. If you were arrested and identified as being gay, you could lose your job, your income, your house, your family.”

I met Alexei in 2010 at his beautifully renovated, mid-century ranch house high in the hills of Pasadena. Sliding glass doors at the back of the house let in abundant sunlight and a sweeping view of the Los Angeles basin. Alexei and his life partner, David Farah, greeted me. It has been 43 years since the Black Cat riot. Alexei is now 74 and retired. “I’ve shrunk three inches,” he admits with an impish grin, but he’s still energetic, outspoken, and every bit the passionate activist who played a role in the course of gay American history.

“Before the Black Cat raid, gays were usually meek and scared. If we were arrested, we’d cop to a lesser charge like disorderly conduct so we wouldn’t have to register as a sex offender for the rest of our lives. We just wanted to be left alone. But that night, something changed.” What changed was that gay people fought back. Two and a half years before the famous Stonewall riots in New York City, they came out of the closet and into the streets of L.A.

“Perhaps it was the reeking mass brutality of this raid that did it,” wrote Jim Kepner in the February 1967 issue of Concern, one of the few gay periodicals in the country at the time. “Or it may have been the slow, cumulative effect of years of hard work by small, struggling organizations telling homophiles that they could fight back—and wondering all the while if anyone was listening.”

“Remember,” says Alexei, “it was 1967. The anti-war protests were going on. Martin Luther King and the civil rights protests were happening. I had marched for black rights, and now I’m thinking: What about us? What about our civil rights?” Indeed the idea of civil rights for gays had been slowly building within the gay community for years. And L.A. was ground zero for much of the pioneering activism that led the way. The first gay political organization in the nation, the Mattachine Society, was founded in L.A. in 1950 by the left-wing activist Harry Hay and a few of his friends. The Mattachine Society’s goals were to change the public perception of gays from sexual deviants to an oppressed minority; to end anti-gay discrimination; and to raise their own personal and political awareness through consciousness-raising discussion groups. In 1954, the Mattachine’s magazine ONE, which was the first gay publication in the country, fought a court battle all the way to the Supreme Court to be able to send their magazine through the mail.

In 1966, a new gay organization was formed in Los Angeles. Pride (Personal Rights in Defense and Education) was more radical, militant, and youth-oriented than previous gay political groups. Pride’s founder, Steve Ginsberg, a young landscape designer, was one of the people who organized the response to the Black Cat raid. Alexei explains how this was accomplished: “There was no Internet back then. All we had was the telephone. So I called ten people, and they called ten people. And they called ten more. We looked around for a place to meet. There was one bar owner who was brave enough to let us meet during the day at his bar in Hollywood called The Hub.” For six intense weeks, a committed group of ten to fifteen gay men talked, planned, and organized a double-pronged strategy of resistance—in the street and in the courtroom.

“What’s important about the Black Cat from a legal perspective,” says attorney David Farah, Alexei’s life partner, “is that the gay men fought the case not on the basis of entrapment, but on the legal theory that they had equal rights and did nothing to be arrested for. That was a tremendous mind-set change. It’s one of those moments in gay history where things changed dramatically. It was a quantum leap.” To fight the legal case, defendants turned to the Tavern Guild, an association of gay bar owners who came together to support gay rights causes. Large jars bearing the sign Tavern Guild Legal Aid Fund were placed in hundreds of gay bars throughout Los Angeles and San Francisco. (It’s estimated that there were over 100 gay bars in L.A. alone.)

At the same time, organizers planned a demonstration in front of the Black Cat bar. “We didn’t want a tiny protest of fifteen or twenty people,” says Alexei. “That had been done before. We wanted as many people out as possible. But we were scared. We were terrified that if we were photographed at the rally we would lose our jobs, our incomes, our families. And there was also the fear of being beaten up by the police. A few months earlier hippies had protested on the Sunset Strip and the kids were attacked and beaten by the sheriff and the police. We knew it could happen to us.” Indeed, Los Angeles in the early 1960’s had become a hotbed of violence between police and the public. It wasn’t just the gay community that bore the brunt of police batons.

Preludes to a Protest

An early blow-up occurred on Memorial Day, 1961. Griffith Park, a huge municipal park in the Hollywood Hills, was filled with picnickers from all over town. It was also teeming with police. At issue was access to the popular merry-go-round, a magnet for young people of all races. Blacks had complained of police harassment when they tried to enjoy the carousel. Authorities claimed that blacks were trying to take control of the whirling fun-machine. That Memorial Day afternoon, a seventeen-year-old black youth was accused of riding the merry-go-round without a ticket. White cops rushed to the scene, violently pulling the kid from the merry-go-round and wrestling him to the ground. Black teens who witnessed the scene were furious. They surrounded the squad car and demanded the release of the young man. One officer opened fire. The crowd responded by throwing bottles at police. After an hour-long mêlée, three officers were injured and five youths were arrested for “inciting a riot.”

A week later, 25,000 teenagers, mostly white, showed up at Zuma Beach in Malibu for a “grunion derby” sponsored by AM rock radio station KRLA. At midnight, sheriffs ordered the partyers to leave the beach. Their demand was met by a shower of sand-packed beer cans. Fifty additional patrol cars were called in to quell the defiant teenagers. That same night, sheriffs had their hands full in Rosemead, a white, working-class community just east of downtown. Several hundred rowdy teenagers had gathered on a street corner and were pelting passing cars with rocks. Before the night was over, 47 youths were charged with rioting, battery, and curfew violations.

Four years later, in 1965, on a sizzling night in L.A.’s African-American community of Watts, Marquette Frye was stopped by police for “driving erratically.” Marquette failed a sobriety test. Neighbors gathered to watch. When police refused to let Marquette’s brother drive the car home, an argument turned into a scuffle. Marquette, his brother, and his mother were all pushed around, handcuffed, and arrested. The crowd objected to this rough treatment by throwing rocks and bottles at the cops. Word of police mistreatment spread through the community—youth to youth, street corner to street corner. Within hours, years of frustration at police brutality, unemployment, poverty, and racial discrimination erupted into four days of rioting and vandalism.

The summer after Watts, teenagers and cops tangled on the Sunset Strip—a twelve block stretch of boutiques, restaurants, coffeehouses and nightclubs which had become a youth stomping ground in the mid-1960’s. Once upon a time, the Strip had been a nocturnal playground for the rich and famous. Movie stars and movie moguls packed legendary clubs like Ciros and Macombo. But times had changed. By the 1960’s, urban decay had set in and the Strip had lost its luster. Now nightclubs like the Whisky-a-Go-Go and Gazaarris were wooing young people with home-grown rock bands like the Byrds, the Mamas and the Papas, Buffalo Springfield, and the Doors.

Two Sunset Strip coffeehouses in particular, Pandora’s Box and the Fifth Estate, were at the center of the growing youth street scene. Pandora’s Box had once been a funky jazz club where musical greats such as Bobby Hutcherson and Les McCann got their start. The club was bought by radio deejay Jimmy O’Neil in 1962 and transformed into a teen coffeehouse. Down the block, the Fifth Estate was managed by Al Mitchell, a leftist filmmaker. The LA Free Press, a weekly underground newspaper, operated from the Fifth Estate basement. Upstairs was a countercultural crucible of poetry readings, folk music, avant-garde film screenings, and political discussions.

On weekend nights, the Strip was jammed with teenagers. Some local business owners were put off by the flower children who clogged the sidewalks but spent little money. Under pressure from these property owners, the police started to harass, arrest, and haul away the “loitering” teens. In response, Al Mitchell formed RAMCOM—the Right of Assembly and Movement Committee. RAMCOM organized a series of protests that turned into violent clashes between long-haired youths and heavily armed riot police. The Sunset Strip “massacres” were immortalized in the Buffalo Springfield anthem “For What It’s Worth” and the low-budget movie Riot On Sunset Strip.

February 11, 1967

As police harassment continued, RAMCOM next planned six simultaneous demonstrations against “police lawlessness.” The demonstrations would take place on Saturday night, February 11, 1967—in Watts, Pacoima, East Los Angeles, Sunset Strip, Venice, and Silverlake. The Silverlake demonstration was organized in conjunction with the gay Black Cat organizers. Eighty thousand flyers announcing the rallies made their way into clubs, bars, coffeehouses, college campuses, and high schools throughout the city.

The Free Press reported that “One of the most interesting and pace-setting reactions to the call to demonstrate came early this week from homosexual organizers who are currently up in arms about New Year’s Eve police raids in a number of Silverlake area gay bars. … Members of such homophile groups as pride and the Council on Religion and the Homosexual decided to sponsor the sixth demonstration to protest the bar raids and resulting beatings and brutality.” In a precedent-setting achievement, gays and straights joined forces to fight against the police violence that affected so many communities throughout the city. But the united front hit some bumps. A prime example: gay activists bowed to pressure from straight organizers, agreeing to omit the word “homosexual” from their flyers.

Meetings, phone calls, flyers, lawyers, court dates, and more phone calls. Finally the big day arrived. On February 11, 3,000 people marched down the Sunset Strip carrying signs such as “Stop Blue Fascism” and “Free the Strip.” Starting at Pandora’s Box, wave after wave of teenagers, flower children, college students, and adults paraded down the Strip in a spirited but peaceful protest.

Most of the other demonstrations flopped, however. In Venice, only about twenty protesters showed up. In Pacoima a tiny group of teen activists were attacked by local gang members, who beat up the kids and ripped up their signs as police watched without interfering. In Watts and East L.A., protests failed to occur at all (perhaps due to the organizers’ lack of connection in the black and brown communities).

The Silverlake rally, however, was a huge success. About 500 protesters gathered outside the Black Cat. The crowd was so large that it spilled out from the sidewalk, filling an adjacent parking lot. Picketers carried signs reading “Abolish Arbitrary Arrests” and “No More Abuse of our Rights and Dignity.” Religious leaders, attorneys, and gay activists addressed the crowd over loudspeakers from the parking lot. Police monitored the scene at the Black Cat from across the street, but kept their distance. Protesters passed out leaflets to passing drivers explaining what the demonstration was all about. Some motorists beeped their horns in support of the demonstrators. Others shouted obscenities as they drove by.

“I was terrified,” remembers Alexei. “I was thinking that someone could drive by and shoot me. So there was fear, but also a sense of pride. We weren’t hiding anymore. I was standing out in front of the public, being myself, saying: This is who I am. I deserve the same rights as everybody else. I deserve not to be beat, not to be arrested just for being me.”

Despite its historical significance as the largest gay protest to date, the Black Cat demonstration was ignored by the mainstream press. However the Free Press covered the rally extensively, declaring: “The Los Angeles homosexual community— long reluctant to come out into the open—now appears ready to launch an entirely new kind of civil rights drive. A drive demanding equal treatment for sexual minorities.”

While it didn’t make the splash that the Stonewall riots did two years later, the Black Cat resistance marked a turning point in gay history. Asserting in court that gays deserve equal protection under the law set legal precedent. The fledgling pride newsletter morphed into The Advocate—the largest and most influential publication in the history of the gay press. Even the naming of the gay pride movement, and the deeply meaningful use of the word “pride” when referring to gay liberation and new gay consciousness, was born with Steve Ginsberg’s pride organization, whose first political action was the protest at the Black Cat.

On November 7, 2008, the Black Cat Tavern was declared a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument. Now home to a Latino gay bar named El Barcito, the building still sports the original sign depicting a smiling black and white cat. Says Alexei: “The fight for civil rights in American happened in many places: at Gettysburg, at Selma and Montgomery, Alabama—these are physical places where people can go and say, ‘This is where black civil rights started.’ The Black Cat protest is our Gettysburg. It’s our Selma. It’s where gay men and women can go and learn about our history. This is where the first large demonstration of gay people in the nation, maybe the world, happened. It happened right here in Los Angeles.”

Eve Goldberg is a writer and filmmaker who lives in northern California. She wishes to dedicate this piece to Stuart Timmons.