Editor’s Note: The following was originally published in the Fall 1999 issue, with a revised version appearing in a specialissue #100, Nov.-Dec. 2012. I bring back this piece to kick off our salute to the 50th anniversary of the declassification of “homosexuality” as a mental illness in the DSM, because I think it provides an excellent introduction to the history of the medical model and takes us up to the fateful events of 1972-’73.

ONE of the most dramatic revolutions in lesbian and gay history, and perhaps the greatest victory of the gay rights movement, is the transformation in psychiatric approaches to homosexuality. Indeed, many current historians argue that late-19th-century doctors constructed modern homosexual identity. “Sodomites” and “pederasts” had long been studied by legal, religious, and medico-forensic experts as criminal or immoral because of their “perverse” acts. However, it was only in the 19th century that the “sexual invert” or “homosexual” emerged in the medical literature as a distinct category of human being. According to historian Michel Foucault, “the homosexual of the 19th century became a personage: a past, a case history and a childhood, a character, a form of life; also a morphology, with an indiscreet anatomy and perhaps a mysterious physiology.”

The accuracy and generalizability of this claim has been much debated as historians have examined new documents suggesting that individuals well before the 19th century or beyond the influence of European medicine had already developed identities as same-sex-loving people (whatever they or we might like to call that identity).

It is, however, clear that Victorian doctors themselves believed that they had discovered a new phenomenon. Their writings also make it evident that they were baffled, disgusted, and terrified by it. Nevertheless, the emerging leaders in psychiatry and sexology believed that “contrary sexual sensation” had to be a profound mental aberration and had to have some biological explanation. Take, for example, one of the first discussions of “contrary sexual sensation” in the American medical press, an exchange of letters published in The Medical Record of New York in 1881. A physician (clearly embarrassed by the subject matter) wrote under the pseudonym Dr. H— to describe “a curious case of prolonged masturbation” currently under his care. The patient was “a highly cultivated gentlemen of high moral character, the father of three or four healthy children, the result of an unusually happy marriage.” However, the patient had a lifelong fondness for “indoor games, female pursuits, and even attire,” especially corsets and tight ladies’ boots with French heels. He largely managed to abstain from masturbating with these articles until he had married and fathered two children. Then he abandoned himself to cross-dressing in painfully tight female clothing and even attended church in a black silk dress. He carried several pictures of himself as a ballet girl, as Queen Elizabeth I, as the Goddess of Liberty, etc. The dismayed and perplexed Dr. H— turned to the conventional remedies of the day: bromides and dietary manipulations (still known to us through Drs. Kellogg and Graham), but to no avail. He concluded his cry for professional assistance: “Have any of your readers had a similar case within their experience? I proposed the name of Gynomania for it.”

Unfortunately for Dr. H—, he never got to coin a new disease. Instead, a subsequent issue of the journal carried a reply from the president of the New York Neurological Society, Dr. Edward C. Spitzka, who was clearly better read in the latest medical literature. He was quick to pronounce a diagnosis of “contrary sexual sensation” and noted that twenty such cases had been described by German and French “alienists.” He lamented that there were undoubtedly more, but they went undetected and were not committed to asylums. They were a result of a “degenerative psychosis” (a hereditary neuropsychiatric disease) and were incurable.

One curious and telling aspect of the case is that Dr. H— never described any same-sex affections in his patient. However, as the terms “contrary sexual sensation” or “sexual inversion” suggest, any kind of cross-gendered behavior, tastes, erotic attraction, or even one’s occupation invoked the suspicion of homosexuality. Relying on recent discoveries that all embryos are “bi-sexual” (i.e., possess both male and female primordial genital tissue), doctors viewed inverts as “psychosexual hermaphrodites.” Using this model, physicians desperately searched for hints of cross-sexed anatomical, neurological, or endocrinological traits that might “objectively” betray a person’s homosexuality (especially if accused of sodomy). More importantly, such crossed-sexed biology might suggest therapies for restoring “normal” masculinity or femininity. These included castration and ovariotomies, implants of “normal” testicles, and hormone therapy. Even into the 20th century, homosexuality remained an obsession of psychiatry: the latest techniques of biological and analytic psychiatry were deployed to explain and treat it, and it became a key pathology for explaining myriad other mental illnesses.

A biological explanation of homosexuality, however, did not necessarily imply its pathologization. From the mid-19th century until today, homosexual researchers and heterosexual scientists sympathetic to the social plight of gay people, hoping to promote wider acceptance, have tried to prove the “natural,” biological, and unalterable quality of homosexuality. They have generally insisted that homosexuality is not a pathology but a natural biological variant.

Particularly before World War II, there were a number of positive depictions of homosexuality in the medical literature. William J. Robinson was chief of the Department of Genito-Urinary Diseases and Dermatology of the Bronx Hospital and a friend of Magnus Hirschfeld, a prominent German homosexual sexologist. As editor of the American Journal of Urology and Sexology, Robinson frequently published items on homosexuality, including a poignant letter in 1919 from an anonymous “invert” who wrote: “[It] is my belief that two men who love each other have as much right to live together as a man and a woman have. Also that it is as beautiful when looked at in the right light and far more equal! … May I not have as high an ideal in my love towards men, as a man towards a woman? Higher no doubt, than most men have toward women!”

Dr. Florence Beery, who also supported the biological model of congenital bisexuality, was even more enthusiastic in defending homosexuals, notably women. Writing in the Medico-Legal Journal of 1924, she enthused: “Homo-sexuals are keen, quick, intuitive, sensitive, exceptionally tactful and have a great deal of understanding. … Contrary to the general impression, homosexuals are not necessarily morbid; they are generally fine, healthy specimens, well developed bodily, intellectual, and generally with a very high standard of conduct.” She dismissed the search for cross-sexed anatomical traits and insisted that generally the “homo-genic woman” had a thoroughly feminine body. It was her temperament that was “active, brave, originative, decisive,” Beery declared. “Such a woman is fitted for remarkable work in professional life or as a manageress of institutions, even as a ruler of a country.” Beery, like many other advocates of biological explanations for homosexuality, was vehemently opposed to the new psychoanalytic views on the subject.

§

In 1905, Sigmund Freud published his groundbreaking Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, which introduced the notions of infantile sexuality, the oral, anal, and phallic stages of development, the castration complex, and penis envy. Although Freud had not treated any inverts before this time, inversion was the subject of the critical first essay as well as the final section of the third essay, on the “Prevention of Inversion.” Freud argued that the “sexual aberrations” were not discreet degenerative pathologies but represented fixations on universal, primitive, infantile stages of erotism. The newborn had the capacity to find any part of the body erotogenic and, furthermore, all children went through a phase of “latent homosexuality” until “normal” heterosexual object choice developed at puberty. While Freud was quite radical in suggesting the universality of homosexuality, he was still a man of his time, for he believed that only heterosexual, reproductive sexuality was normal and healthy. Homosexuality represented a form of arrested sexual development resulting from traumatic parent-child dynamics. Nevertheless, Freud did not believe homosexuals were necessarily unhappy and dysfunctional people; nor did they need to be “cured.”

Dr. Abraham Brill, one of Freud’s early American promoters and translators, was even more radical in his assessment. Writing in the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease (1919), he reaffirmed that, “everyone is more or less homosexual, which enabled them to live in friendly relations with their fellow beings of the same sex.” Most homosexuals, he claimed, did not want to be cured; nor could they be. The only homosexuals who did seek therapy were of the “compulsion neurotic type.” Psychoanalysis of homosexuals who were forced into therapy and who did not want to be cured was “simply a waste of time and money.” Brill argued that it was more useful to encourage the family to be broad-minded. Writing at the end of the Roaring Twenties, Dr. Clarence P. Oberndorf noted in the Urologic and Cutaneous Review (1929) that, at least in educated circles, American attitudes towards sex were far less Victorian. He even criticized as outdated Radclyffe Hall’s portrayal of the “distressed and fatalistic wail” of the lesbian heroine in The Well of Loneliness (1928).

Upon Freud’s death in 1939, and with the U.S. entry into World War II, psychoanalytic views of homosexuality took a distinct turn for the worse. Psychoanalyst Sandor Rado in 1940 challenged Freudian orthodoxy by denying the universality of infantile bisexuality and by insisting that homosexuality was distinctly pathological and potentially curable. Typically, analysts blamed homosexuality on a close-binding, overprotective mother and a detached, hostile father. Some psychoanalysts even advocated the additional use of hormone and shock therapies for recalcitrant patients who “posed too much resistance to treatment.”

Psychoanalysis also gained enormous professional clout thanks to its involvement in the war effort. The Selective Service wanted to screen out inductees who might buckle under pressure and undermine company morale. “Homosexual proclivities” were one of the mental handicaps to be referred for more expert scrutiny and exclusion. Dr. Manfred Guttmacher complained in Neuropsychiatry in World War II (1966) that “there was that pathetic group of homosexuals who had denied their abnormality to induction examiners and who had blindly hoped to adjust by living a robust life among thousands of normal military men. … Others with strong latent tendencies developed psychosomatic disorders and acute anxiety states.” Psychiatrists also assessed for “reclaimability” the thousands of armed forces members diagnosed with “pathological sexuality.”

The stresses of war and crowded all-male living conditions seem to have prompted numerous cases of “acute anxiety states” with “homosexual panic.” The term first appeared in Dr. Edward Kempf’s textbook Psychopathology (1921), which described typical cases in which a young man became convinced that friends or comrades believed he was homosexual, stared at him oddly, whispered insults like “cock sucker,” “woman,” “fairy,” and tried to engage him in fellatio or sodomy. Kempf explained that it resulted from “the pressure of uncontrollable perverse sexual cravings.” In the most severe cases, it became chronic and was indistinguishable from dementia præcox or schizophrenia. Ten years earlier, Freud had proposed that paranoia was frequently the result of repressed homosexuality being transformed through the defense mechanisms of reaction formation (“I hate him”) and projection (“he hates me”). Analysts increasingly believed that schizophrenia in general was caused by homosexuality. One analyst even called schizophrenia the “twin brother” of homosexuality.

Homosexuality increasingly became the culprit for just about every other psychopathology. In addition to psychotic disorders, it was connected to all neurotic disorders, alcoholism, even promiscuous heterosexuality (or Casanova syndrome). Thus Dr. Benjamin Karpman was exaggerating only slightly when he declared in 1937, “The problems of psychiatry will not be solved until we solve the problem of homosexuality.”

§

The problem of homosexuality only grew after the war, particularly following the publication of Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948), by Alfred C. Kinsey, Wardell Pomeroy, and Clyde Martin. The “Kinsey Report” disclosed astoundingly high rates of homosexual behavior (as well as masturbation and other perversities). It quickly became a global bestseller and inspired the formation of “homophile” groups such as the Mattachine Society. Many psychiatrists and sexologists objected to its findings and were offended by Kinsey’s sharp critiques of both hormonal and psychoanalytic explanations of homosexuality. Most notably, Kinsey argued that sexual orientation was not binary (either hetero- or homosexual) or fixed over one’s lifespan. The thought that homosexuals were numerous and not all flamingly evident no doubt also fueled the gay purges that began in 1950. Like “Reds,” “sex perverts” might be corrosive yet invisible.

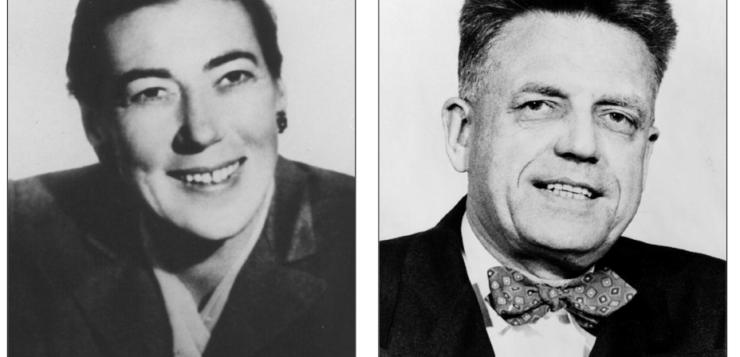

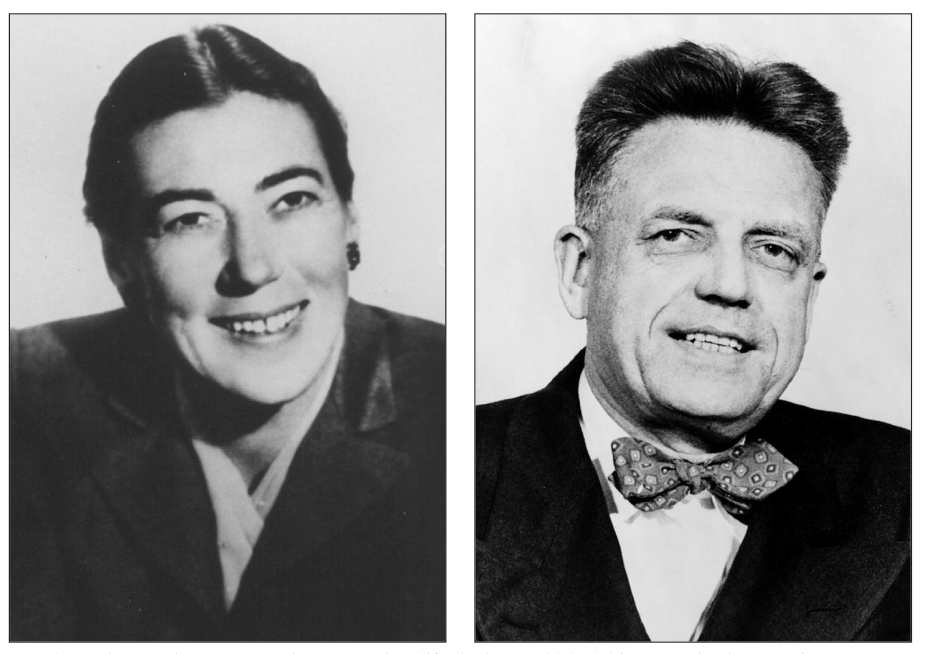

Further challenges to the pathological view of homosexuality came from psychologist Evelyn Hooker at UCLA. Through one of her students, she was introduced to the gay community of L.A. and began conducting psychological testing of these nonclinical subjects in the 1940s. Previous research had been based on prison cases or homosexuals seeking psychiatric treatment. Hooker’s gay subjects, however, were not significantly different in their psychological adjustment from matched heterosexual controls. Hooker began to publish her findings in the late 1950s and was a welcome speaker at homophile group meetings. She chaired a National Institutes of Mental Health research panel on homosexuality, whose initially suppressed report in 1969 decried the widespread mistreatment of homosexuals and called for decriminalization and greater social acceptance as the way to improve their mental health.

At the time, a variety of behaviorist conversion therapies were being actively promoted. Electrical shock aversion therapy (first used to treat alcoholism in the 1920s), chemical aversion therapy with emetics (developed the 50s), covert sensitization, and other conditioning therapies all tried to re-orient erotic attraction by associating homoerotic images with discomfort. They generally failed in the long run and later provoked visceral opposition by gay rights activists. At the 1970 American Psychiatric Association (APA) annual meeting, Dr. Nathaniel McConaghy’s presentation on aversive conditioning exploded in gay pandemonium as activists accused him of being a vicious torturer.

The work of Kinsey, Hooker, and others all emboldened a new brand of post-Stonewall gay liberation activists ready to engage in dramatic and confrontational tactics, including disrupting APA meetings and demanding equal time to refute the theories of homosexual pathology. With the assistance of key supporters within the APA, a panel of “non-patient” gays spoke at the 1971 APA meeting. At the 1972 meeting a similar panel included a gay psychiatrist, John E. Fryer, who wore a mask to preserve his anonymity. That year the APA’s Nomenclature Committee began considering the pathological status of homosexuality as presented in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd edition (DSM II). With growing support for reform among psychiatrists, after extensive debate at the 1973 meeting, and with much behind-the-scenes lobbying both for and against de-pathologization, the APA Board of Trustees voted on December 15, 1973, to delete homosexuality from the DSM. Sensitive to many psychiatrists’ profound theoretical and emotional commitment to the pathological nature of homosexuality, the Board added the classification of “sexual orientation disturbance” (later labeled “ego-dystonic homosexuality”) for individuals who are disturbed by their same-sex orientation. Newspapers around the world reported the decision, with one writer wryly noting it was the single greatest cure in the history of psychiatry.

Many prominent psychoanalysts, such as Charles Socarides and Irving Bieber, were not pleased with this outcome and mounted a vocal battle against the change, ultimately forcing it to a vote by the APA membership. In 1974, a majority of APA members ratified the declassification of homosexuality. The American Psychological Association followed suit in 1975, and the social workers’ association in 1977. Gay and lesbian caucuses have sprung up within all of these organizations and have been formally recognized. Out gay and lesbian researchers have explored the mental health challenges and successes of gay people within a homophobic culture. The American Psychoanalytic Association proved most resistant: only in 1992 did it officially reverse its longstanding, unspoken policy of excluding homosexuals from advancement in psychoanalytic institutes. The 1994 edition of the DSM eliminated any diagnosis of homosexuality, and the APA has officially criticized gay “conversion therapy” as useless and harmful.

In the span of a century, the diagnosis of homosexuality had come full circle, from being “discovered” as a profound psychiatric illness to being a normal variation of human sexuality. This history serves as a powerful example of the social and political malleability of supposedly objective scientific knowledge.

References

Bayer, Ronald. Homosexuality and American Psychiatry: The Politics of Diagnosis. Princeton University Press, 1987.

Bérubé, Allan. Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II. The Free Press, 1990.

D’Emilio, John. “The homosexual menace: the politics of sexuality in Cold War America,” in Passion and Power: Sexuality in History, Kathy Peiss and Christina Simmons, eds. Temple University Press, 1989.

Foucault, Michel. Histoire de la sexualité: La volonté de savoir. Gallimard, 1976. (Translated as A History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction).

Vernon Rosario is a historian of science and an Associate Professor of Psychiatry at UCLA.