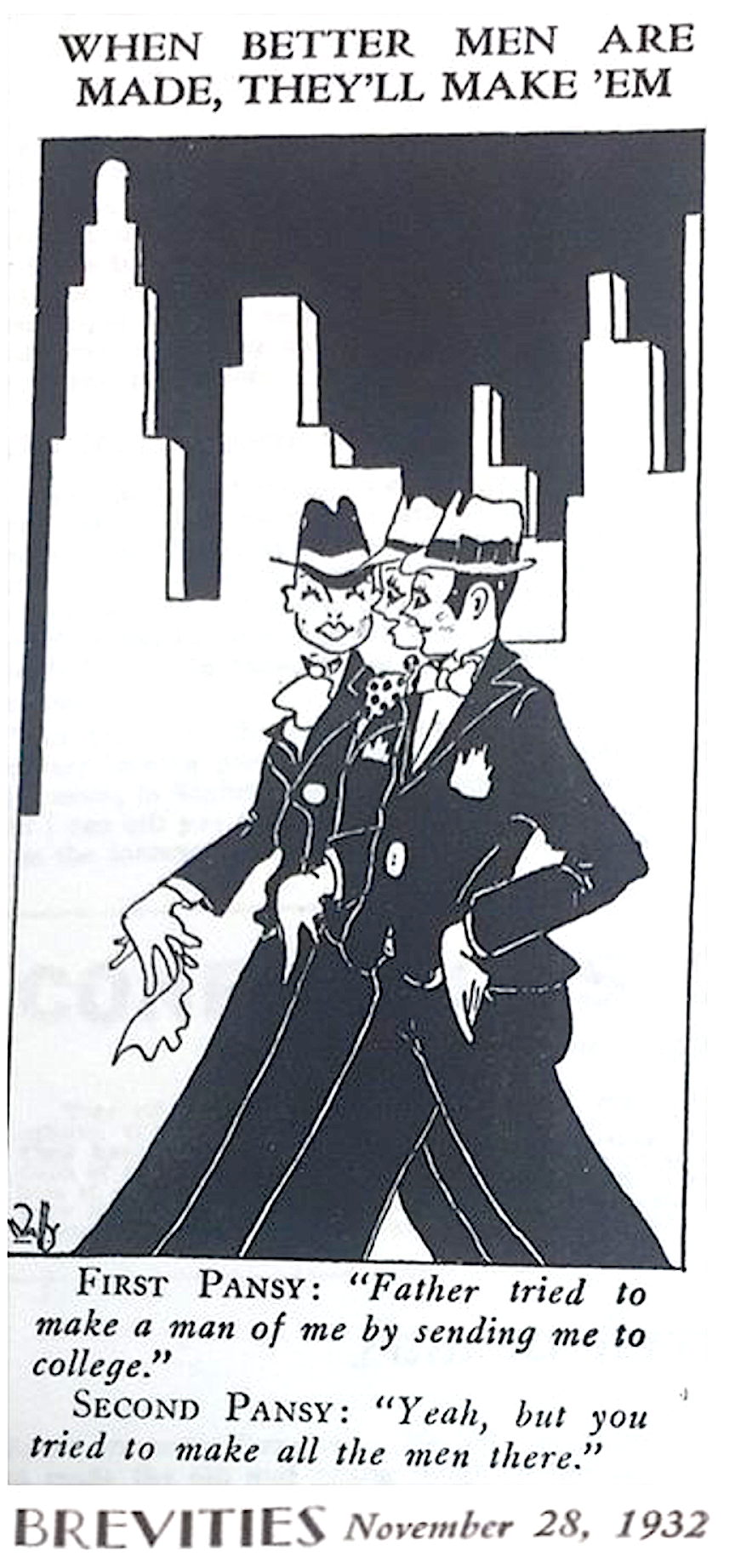

ONE HUNDRED YEARS AGO, New York City was one of several U.S. cities that was in the midst of what has come to be known as the “Pansy Craze”—George Chauncey’s coinage in Gay New York—or what I prefer to call the “Queer Craze.” To be sure, as a cultural phenomenon, the Craze was short-lived. After the Roaring Twenties there followed a backlash not unlike the one that MAGA and alt-right conservatives are mounting against today’s LGBT communities. It’s a familiar pattern of progress in civil rights giving rise to a reactionary response.

If past is prelude, revisiting the Pansy Craze era might help us to navigate the current culture wars. In this spirit, I wrote a historical novel titled Craze that was recently published by Jaded Ibis Press. The narrative is written from the point of view of Henri Adams, a lesbian whose best friend Crystal is a renowned drag performer known as the Queen of Tarts. The following brief synopsis sets the stage for a deeper dive into the Pansy Craze and a look at the historical parallels between then and now.

Fresh off the boat from Paris, Henri Adams (née Henrietta) assumes that New York’s nightlife will pale in comparison with her escapades in the sapphic salons of Gertrude Stein and Natalie Barney. Little does she know that New York is on the verge of a cultural eruption that would catalyze the raucous eroticism of the Roaring Twenties. An American art critic armed with letters of introduction from Pablo Picasso and Romaine Brooks, Adams lands a job with New World Art, a magazine catering to patrons of the nascent avant-garde art scene on this side of the Pond. But notwithstanding this professional success, her love life is virtually nonexistent—that is, until a queen named Crystal offers to show her around the clandestine world of speakeasies and drag balls. Paradoxically, Prohibition fuels the Craze, funneling jams (heterosexuals) and queers alike into the mob-run realm of illegal nightspots and their pleasures. Eventually, as the Jazz Age reaches a fever pitch of revelry, the Craze almost goes mainstream. But the party can’t last forever. Faced with Depression-era crackdowns, Henri and Crystal calculate the risk of fighting back, a historically fraught and distressingly familiar calculation.

One of the most remarkable things about the Queer Craze is the extent to which its performance of gender fluidity prefigures our own. From a contemporary perspective, for example, it’s not clear whether Crystal experiences themself as transvestite or transsexual, a distinction that troubles contemporary gender discourse. The same might be said of Djuna Barnes’ depiction of Matthew O’Connor in the classic lesbian novel Nightwood (1936) and, ten years earlier, Virginia Woolf’s portrayal of Orlando in 1928’s Orlando: A Biography. The following series of quotations from Orlando, Nightwood, and Craze provide some historical context for nonbinary gender discourse, whose roots date back to the Craze era:

Orlando had become a woman—there is no denying it. But in every other respect, Orlando remained precisely as he had been. The change of sex, though it altered their future, did nothing whatever to alter their identity. [From Orlando]

Orlando had become a woman—there is no denying it. But in every other respect, Orlando remained precisely as he had been. The change of sex, though it altered their future, did nothing whatever to alter their identity. [From Orlando]

In the old days I was possibly a girl in Marseilles thumping the dock with a sailor and perhaps it’s that memory that haunts me. The wise men say that the remembrance of things past is all that we have for a future, and am I to blame if I’ve turned up this time as I shouldn’t have been, when it was a high soprano I wanted, with a womb as big as the king’s kettle, and a bosom as high as the bowsprit of a fishing schooner? [From Nightwood]

I don’t mean to say Crystal identified as a woman per se. Crystal wasn’t so much a woman as a queen, a body on the spectrum of femininity without feeding into prescribed gender roles. By the same token, I wasn’t mannish any more than I was womanish. I was androgynous, a whole new species of being—or should I say becoming—a gender in motion. [From Craze]

There’s a lot to unpack here, beginning with Virginia Woolf’s use of “their identity” to describe Orlando’s future life. Throughout the novel, Orlando is more “they” than “he” or “she,” regardless of how they’re perceived. The idea that their “change of sex … did nothing whatever to alter their identity” makes the point that gender is derivative, not determinative of who you are. Similarly, Nightwood’s Matthew O’Connor is a consummate gender shapeshifter who still experiences themself as “a girl in Marseille,” despite having “turned up this time” as a so-called man in Paris. As for Crystal in Craze, they are “a gender in motion,” an embodiment of what we call “nonbinary” and what they called “androgyny” during the heyday of the Craze.

A lot is at stake here, no matter how you parse gender fluidity in Orlando, Nightwood, and Craze. Then as now, gender tends to get caught up in society’s culture wars. Apropos the title of Judith Butler’s recently published book Who’s Afraid of Gender?, bigots and neo-fascists are afraid of gender fluidity, which flies in the face of their authoritarian dichotomies. Accordingly, drag queens and drag kings are dehumanized; the trans community is attacked. We need to understand how this has happened historically. The brutal Depression-era crackdowns were followed by four decades of persecution, until the Stonewall Riots ushered in the Gay Liberation movement.

A lot is at stake here, no matter how you parse gender fluidity in Orlando, Nightwood, and Craze. Then as now, gender tends to get caught up in society’s culture wars. Apropos the title of Judith Butler’s recently published book Who’s Afraid of Gender?, bigots and neo-fascists are afraid of gender fluidity, which flies in the face of their authoritarian dichotomies. Accordingly, drag queens and drag kings are dehumanized; the trans community is attacked. We need to understand how this has happened historically. The brutal Depression-era crackdowns were followed by four decades of persecution, until the Stonewall Riots ushered in the Gay Liberation movement.

Counterintuitively, these crackdowns were catalyzed by the normalization of alternative identities. In other words, they were a response to how not strange nonbinary gender identities were becoming in some cities (Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, in addition to New York) in the 1920s. (I’m using the word “strange” advisedly, in keeping with the theme of this issue of The G&LR, though the word may not line up perfectly with our word “queer.”) The Queer Craze didn’t just infiltrate sleazy speakeasies like Frank’s Place near the Brooklyn Navy Yard, but gave rise to a “new normal” that seemed less and less shocking over time. The Cotton Club, a Harlem venue catering exclusively to white, nominally heterosexual customers, featured Gladys Bentley, whom Langston Hughes described as “an amazing exhibition of musical energy—a large, dark, masculine lady” decked out in a signature white top hat, tuxedo, and tails. Karyl Norman, the self-styled Creole Fashion Plate, headlined at the Pansy Club on the corner of Broadway and 48th Street, which opened its doors in 1930. Even the Odd Fellows, a venerable charitable fraternity, got in on the action, sponsoring the Hamilton Lodge Masquerade and Civic Ball, one of Manhattan’s most celebrated queer extravaganzas. Here’s how I described it in Craze (note that “slummers” were well-heeled pleasure seekers who went to these clubs to “slum it”):

Ethel Waters was there, next to Tallulah Bankhead and Nora Holt. A’Lelia Walker’s loge was like a miniature salon, a who’s who of the Harlem Renaissance. Langston Hughes was seated to her left, Countee Cullen on her right, flanked by Alain Locke and several other literary luminaries. They affected an air of dignified detachment, distinguishing themselves from slummers in the general seating section. Across the balcony, several Astors and a Vanderbilt followed suit, acting like Roman patricians perched high above the drag equivalent of gladiatorial games at the Colosseum. The boundary separating us from them was notoriously permeable.

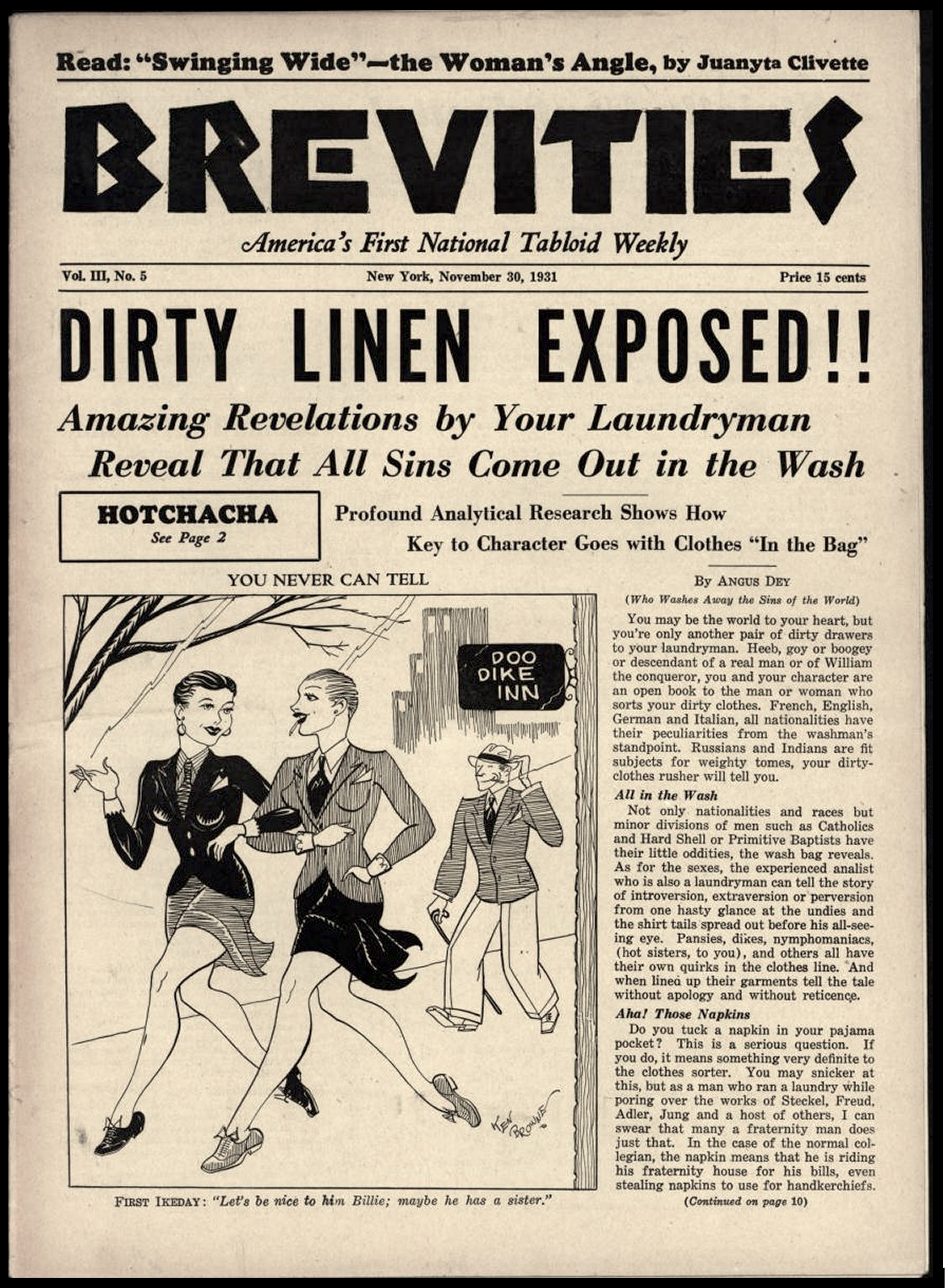

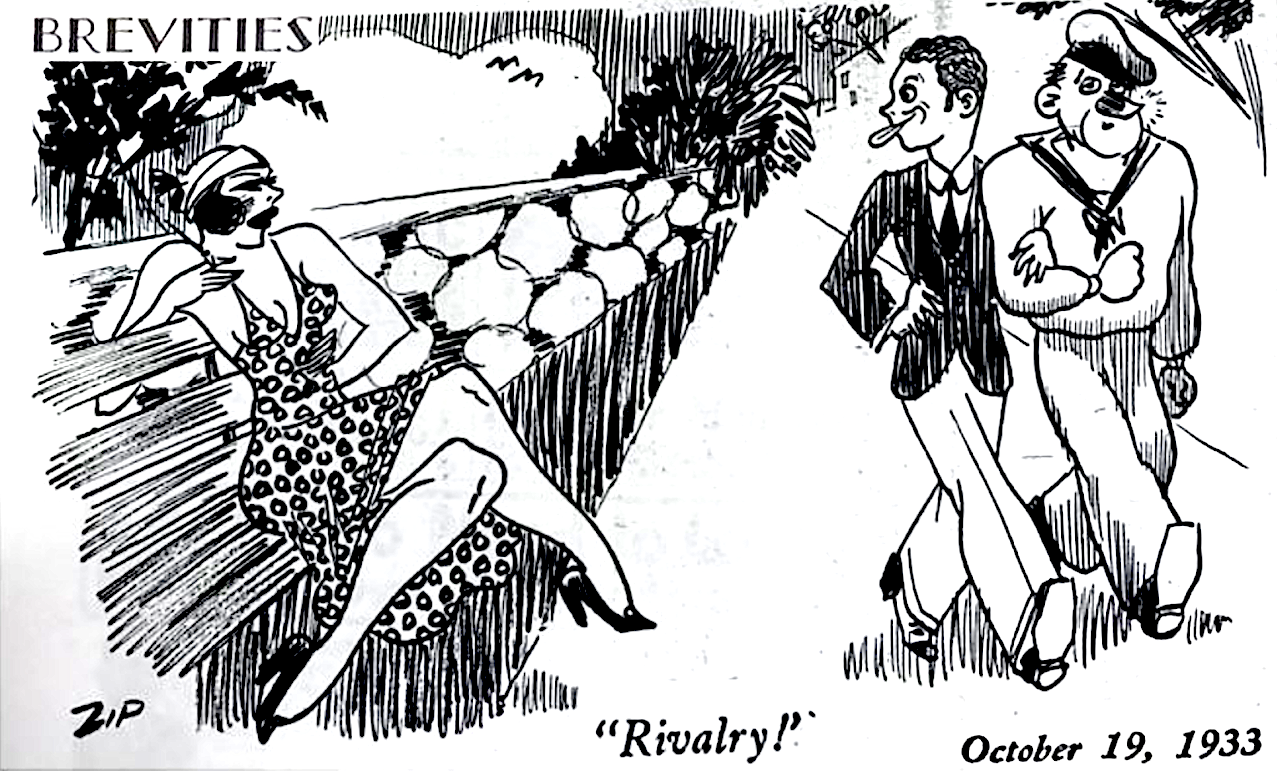

Staging back-alley drag balls was one thing; performing for Astors and Vanderbilts was quite another. What’s more, slummers didn’t just indulge in voyeuristic pleasures; they sampled the seafood, so to speak—a metaphor on full display in periodicals like Broadway Brevities, one of several mainstream publications covering the Pansy Craze. Most of slummers were more titillated than scandalized by the porous boundary between “us” and “them.” But it’s also the case that our concept of homosexuality as the opposite of heterosexuality wasn’t invented until after the demise of the Queer Craze. What had once been an anarchy of genders and desires came to be reduced to the strict binary of subsequent decades with the onset of the Depression and World War II and the postwar years.

In retrospect, the Roaring Twenties are a cautionary tale of what can happen when puritanical prigs find it convenient to scapegoat queer people for their guilty pleasures. What was at stake was more than just the right of stage performers to defy certain boundaries. Gender fluidity tends to destabilize binary power structures—the same ones that privilege men over women and heterosexuals over every other conceivable orientation and identity. When strictly enforced laws governing normality are threatened, fascists crawl out of the woodwork. Virginia Woolf’s clear-eyed assessment of this dynamic in A Room of One’s Own (1929) pits androgyny against the rise of fascism in Italy and Germany on the eve of World War II:

If one is a man, still the woman part of his brain must have effect; and a woman also must have intercourse with the man in her. Coleridge perhaps meant this when he said that a great mind is androgynous. Perhaps a mind that is purely masculine cannot create, any more than a mind that is purely feminine.

For one can hardly fail to be impressed in Rome by the sense of unmitigated masculinity; and whatever the value of unmitigated masculinity upon the state, one may question the effect of it upon the art of poetry. The Fascist poem, one may fear, will be a horrid little abortion such as one sees in a glass jar in the museum of some county town.

Here Woolf sounds the alarm, citing “unmitigated masculinity” as the root cause and primary beneficiary of binary gender politics. Gertrude Stein echoed her assessment of the threat, warning that “there is too much fathering going on … father Mussolini and father Hitler … and father Franco is just commencing and there are ever so many more ready to be one.”

We would do well to heed their warnings as yet another cult of masculinity fuels the current backlash against nonbinary gender equality. Celebrating the centennial of the Queer Craze serves as a reminder that history repeats itself, for better or for worse. Forewarned is forearmed, provided we’re willing to fight back this time around. As I wrote in Craze:

Just as surely as the Jazz Age catalyzed a queer Renaissance, the Depression era thrust us back into the Dark Ages. I’m tempted to say the rest is history. But that would only account for the worst of times. The best of times deserves its own chapter … the story of the first flowering of queer culture in America. If it happened once, it can happen again. What’s past is prologue, remember?

Margaret Vandenburg’s novels include Craze, a Jazz Age portrait of queer New York, and An American in Paris, a romp through the sapphic salons of Gertrude Stein and Natalie Barney.