TWO WEEKS AFTER the death of the photographer Robert Giard this past summer, I was asked to call several friends of his, unknown to me, who might not yet have heard the bad news. It was also an occasion to inform them of the memorial service which was to be held a couple of weeks hence. Each call was uniquely difficult. When I phoned a female friend of Bob and his lover, Jonathan Silin, to inform her that Bob had died suddenly and unexpectedly on a bus en route to Chicago, she cried out on the other end, followed by a pained question, “What’s happening to the world?” She had it exactly right. The world was out of joint if it was a world without Robert Giard in it.

Not only was Bob a superb photographer, whose contribution to the cultural store of the gay and lesbian community will now, one hopes, find its truest and deepest measure, but he was also regarded by vast numbers of people as a person of wisdom, enormous sympathies, wide but lightly-worn erudition, and an innate nurturing quality. Many in our community know of Bob Giard as the man who had been photographing gay and lesbian writers across America for two decades. Though this was an ongoing project, by the mid 1990’s Bob had a critical mass of portraits, enough to allow a significant portion of the collection to be published in 1997 by MIT Press in a volume entitled Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay and Lesbian Writers. The following year, no less an institution than the New York Public Library exhibited a substantial selection of these images in an exhibition under the same name. Other exhibitions of the work followed, including one at the San Francisco Public Library which, like the NYPL, was beginning to collect portions of his corpus of work—some six hundred portraits at the time of Bob’s death.

To his death at age 62, Bob was a person of modest manner and means. Never having gotten a driver’s license, he biked around the communities of the South Fork—fashionably known as The Hamptons—doing the daily chores like shopping and picking up the mail at the local post office. He was a man who carried his equipment in a backpack, who flew to cities across America and then traveled by subway, bus, or arranged a car pickup through friends, to reach his portrait models. By the time he got to a writer’s home, he had read all or much of the writer’s work. He worked quietly, efficiently, putting himself and his sitter at ease. The qualities that distinguish his portraits might be summarized as honesty, rigor, directness, and empathy.

Particular Voices is encyclopedic in scope, like August Sander’s 1920’s photographs of Germans in varying professions, but without the generalizing impulse that has Sander finding representative types to stand in for the group. Giard’s feeling for his subjects can be compared to that of Julia Margaret Cameron in her Pictorialist studies of friends and family, but without the aureole of sentimentality that informs her Victorian manner. His images are as unadorned and un-idealizing as Mike Disfarmer’s catalogue of the citizenry of Heber Springs, Arkansas, which were taken before and during World War II—but without Disfarmer’s strict studio frontality or limited ethnic make-up.

It seems appropriate to reference historical figures when discussing Bob’s work, for he was an artisan photographer of the old school. Every picture was hand-printed out of a small photo lab in his home in Amagansett, Long Island, on paper stock he chose with great care, the prints “spotted” by hand as the final finish. His direct, unblinking, sometimes overly earnest style is closer to the 19th century—to David Octavius Hill, Nadar, or Etienne Carjat—than to the knowing and sly ironic stance of contemporaries like Robert Mapplethorpe or Herb Ritts (whose images may have more immediate surface appeal—full of higher-contrast tonal sensualities, and beauty announced as an advertisement for itself).

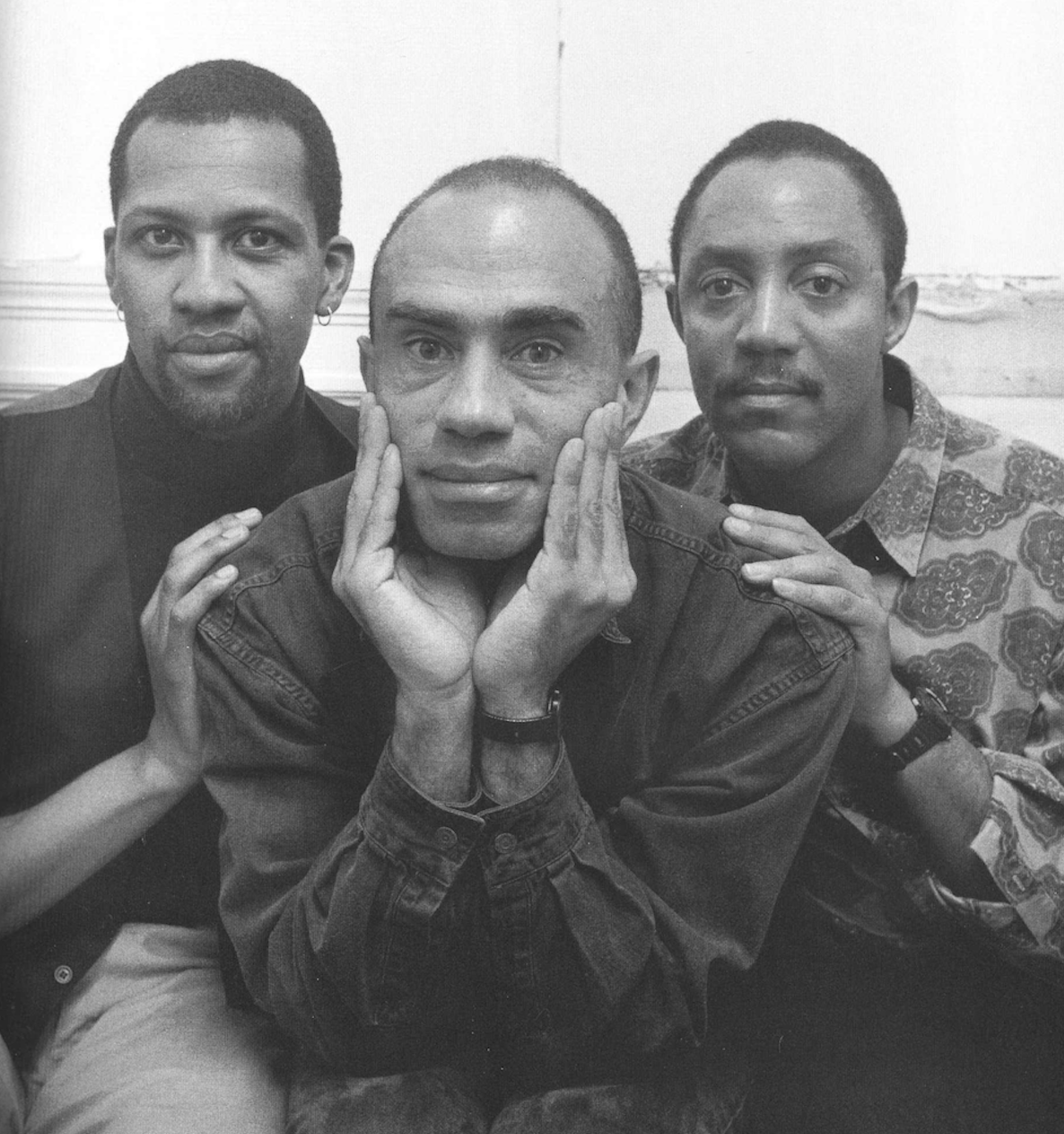

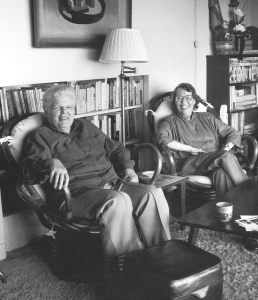

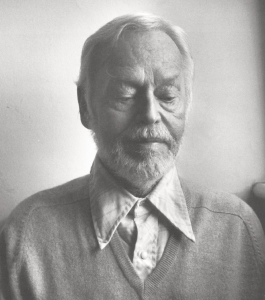

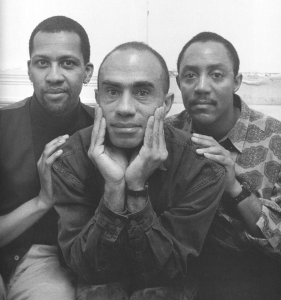

Bob took his pictures of gay and lesbian writers indoors and out, close-up and at mid-range, alone or with family, friends, pets, or lovers. The Giard “catalogue” of writers includes the very well-known and the barely published, aging icons and the still dewy young, including: the late Harry Hay, the late Charles Henri Ford, May Sarton, Barbara Gittings, Jewelle Gomez, Alison Bechdel, Esther Newton, Rafael Campo, Samuel R. Delany, Andrew Holleran, Maria Irene Fornes, Shay Youngblood, Adrienne Rich, Pomo Afro Homos, James Purdy, Edmund White, Edward Albee, Lillian Faderman, Leslie Feinberg with Minnie Bruce Pratt, Tony Kushner, Gloria Anzaldúa, and the list goes on and on. As this roster indicates, Particular Voices includes novelists, cultural and social historians, playwrights, scholarly theorists, poets, and performance artists. That Bob managed in the space of just under two full decades to crisscross America and take incisive portraits of some six hundred gay and lesbian writers speaks to the tremendous human sympathies he brought to the task. This includes his strong feminism which was not just a political goal but a way of life. It was what made him perfect to be chosen the official portrait photographer of The Thanks Be to Grandmother Winifred Foundation, whose mandate, until its recent demise, was to support social and creative projects of women who were at least 54 years of age.

What Bob Giard gave us was a wide-angle view of our literary community, manifesting our class, ethnic, and generational variety in his portraits. And he did so specifically in response to the stunning losses from AIDS when, in 1985, having seen Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart, he sensed time passing as an urgent call to action. He had already been photographing artist and writer friends and had created stunning images of the male nude and the landscape of Long Island’s South Fork. Now he decided he would devote himself to “recording something of note about our experience, our history, and our culture.” In the resulting images we find a mix of gravity and wit, of delight and even awe. In Bob’s pictures, each person is indelibly him- or herself: smiling and energetic Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, the glorious grandmothers of Bilitis, in front of a bookcase; the sculptural profile of a thoughtful, bearded Lev Raphael looking like a young testament prophet in the making; Assotto Saint, his beautiful, sexually ambiguous face cast upward into the light, a poetic Joan of Arc hearing his own muses.

Although he graduated from Yale as a literature major, Bob was raised in working-class circumstances in Hartford, Connecticut. Interested in all kinds of people, he could engage in conversation with the prince as well as with the pauper. He could discuss French or American literature, foreign cinema from the 1950’s and 60’s, or Hollywood hunks from nearly any era, but especially from his youth, when he was most susceptible to their charms. His laugh was giddy and infectious. He had no social airs despite living in a beach community that has in the last several decades become the haunt of grasping arrivistes. His own staunch work ethic urged him forward, not because there was a pot of gold or even fame at the end of his particular gay rainbow—alas, on this score, he might perhaps have been a little too naïve for his own good—but because the project was ever expanding and demanded his attention. He always tried to keep up with gay and lesbian writing on its many fronts, for he knew there was another generation coming up that had to be photographed.

For generations to come—especially, but not exclusively, for generations of GLBT people to come—Bob’s Particular Voices will stand as a testament to an extraordinary cultural moment in America: an era when members of the gay and lesbian community, previously vilified, stood up and spoke their particular truth. By offering our faces to the world, and also by offering the faces of some of our forebears to the world, Bob acknowledged the valedictory nature of this cultural moment. Bob knew this also about the medium to which he devoted himself. “Photography is par excellence a medium expressive of our mortality,” he wrote, “holding up, as it does, one time for the contemplation of another time.”

To say simply that he will be missed hardly touches upon the feelings of those who knew him. We are bereft. He was a friend to whom one went for counsel and kibitzing. We have lost our compass and must now find our own way. It is already a colder world without him.

The Robert J. Giard, Jr. Memorial Fund has been formed to preserve Robert Giard’s photographic legacy. For details, see Bulletin Board, page 48, in this issue.

Allen Ellenzweig is the author of The Homoerotic Photograph (1992) and a frequent contributor to this journal.