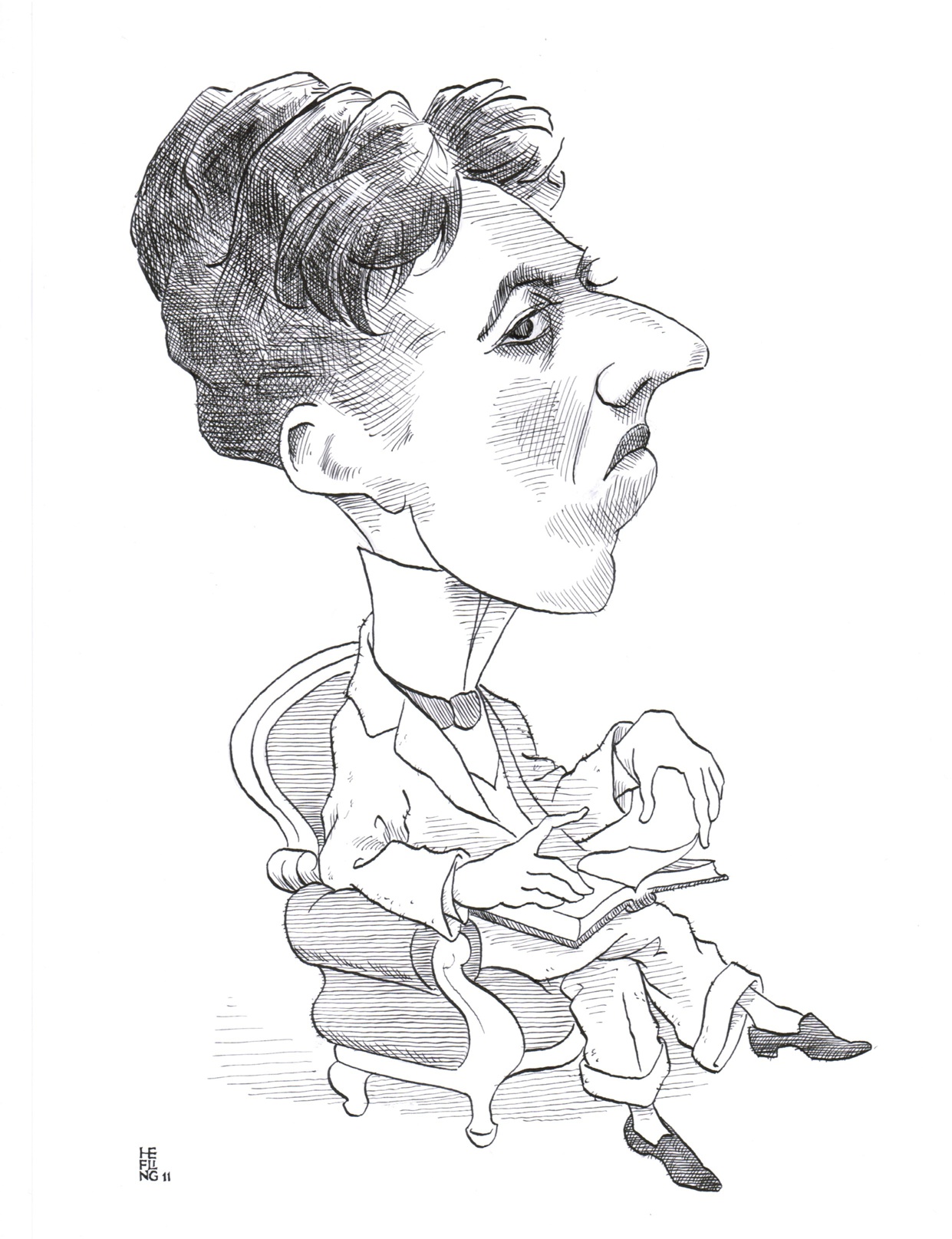

THE FACT THAT Ronald Firbank was an innovator in his medium, that he was a humorous commentator on social mores, has long been recognized. That his novels are wise as well as witty has not been generally acknowledged, a fact that may be due to the strong influence of Oscar Wilde upon his work. However, as literary and cultural criticism has come increasingly to appreciate Wilde as a major writer and as a prophet of our age, Firbank’s fortunes have risen accordingly.

Firbank, who wrote in the early 20th century and was, like Oscar Wilde, a gay man, fixed upon Wilde early on as his guiding inspiration and patron saint in both life and art. The gist of the Wildean wisdom that Firbank internalized and expressed through his fiction is presented, however obliquely, in his first published novel, Vainglory, in the character of Claud Harvester, a sophisticated dilettante (like Firbank himself). After an extended youth of restless wandering and existential “groping,” Harvester “began to suspect that what he had been seeking for all along was the theater. He had discovered truth in writing plays. In style—he was often called obscure, although, in reality, he was as charming as an apple-tree above a wall.” In short, Harvester had discovered style, that Wildean virtue summed up in the dictum, “Truth is entirely and absolutely a matter of style.” Wilde’s repeated argument in his essays is that Truth is fundamentally an æsthetic rather than an epistemological or ethical phenomenon. Taste is at the heart of human nature, he maintained, and indeed of Nature itself, which is, after all, “our creation.” This is not to say that Nature may be made into anything we will it to be; rather, it is to affirm that what we instinctively consider to be natural is according to our taste.

Firbank, who wrote in the early 20th century and was, like Oscar Wilde, a gay man, fixed upon Wilde early on as his guiding inspiration and patron saint in both life and art. The gist of the Wildean wisdom that Firbank internalized and expressed through his fiction is presented, however obliquely, in his first published novel, Vainglory, in the character of Claud Harvester, a sophisticated dilettante (like Firbank himself). After an extended youth of restless wandering and existential “groping,” Harvester “began to suspect that what he had been seeking for all along was the theater. He had discovered truth in writing plays. In style—he was often called obscure, although, in reality, he was as charming as an apple-tree above a wall.” In short, Harvester had discovered style, that Wildean virtue summed up in the dictum, “Truth is entirely and absolutely a matter of style.” Wilde’s repeated argument in his essays is that Truth is fundamentally an æsthetic rather than an epistemological or ethical phenomenon. Taste is at the heart of human nature, he maintained, and indeed of Nature itself, which is, after all, “our creation.” This is not to say that Nature may be made into anything we will it to be; rather, it is to affirm that what we instinctively consider to be natural is according to our taste.

Through his internalization of this Wildean wisdom, Firbank in effect joined his individual search for truth—his restless wandering and spiritual groping (he converted to Catholicism while at Cambridge but later seemed to have abandoned it)—to his exploration, expression, and refinement of style; so that his fiction became for him a conjoined æsthetic and existential effort at self-realization. It was an effort to which he devoted himself with the ardency and sincerity of the aspiring saint—a figure that is variously and hilariously travestied throughout his work. On the other hand, the self and style that is embodied in Firbank’s work is anything but earnest. On the contrary, it is wayward, capricious, eccentric, artificial, and fantastical—in other words, a veritable compendium of the more playful and ornamental aspects of human temperament.

A great deal of the historical misreading and continual undervaluing of Firbank’s fiction is the result of the confusion between his entirely earnest and serious effort at the fictional realization of the truth of both self and style, and the playful and eccentric nature of the self and style that his novels realize. E. M. Forster was, sadly, all too typical in assuming that Firbank’s “frivolous” subject matter denoted a frivolous author, contending that all of Firbank’s novels are characterized by “the absence of a soul … there is nothing to be saved or damned” in them, for they have “no relation to philosophic truth.” Forster concluded that, because Firbank’s novels fail to “introduce the soul [and]its attendant scenery of Right and Wrong,” they are “fundamentally unserious.”

Certainly Firbank’s novels fail to include the conventional novelistic “scenery of Right and Wrong,” the entire absence of which is one of their chief virtues and a remarkable ethical and æsthetic achievement in its own right. Mid-century British critic Cuthbert Wright astutely noted of Firbank that “it was not so much that he defied certain social and moral conventions; it was as if he had never heard of them.” In any case, Forster’s criticism is valid only if one grants him the assumption that “Right and Wrong” are characteristics of the “soul,” but this is not an assumption that Firbank’s fiction grants. Rather, Firbank’s novels creatively embody and express the Wildean assertion that the truth of the soul is more fully realized by æsthetic rather than ethical means. “Æsthetics are higher than ethics,” Wilde wrote, “They belong to a more spiritual sphere. To discern the beauty of the thing is the finest point to which we can arrive. Even a color sense is more important, in the development of the individual, than a sense of right and wrong.”

Wilde follows up this provocative pronouncement near the conclusion of “The Critic as Artist” with the observation that the difference between ethics and æsthetics in the “sphere of conscious civilization” may be compared to the difference between natural and sexual selection in the realm of the material world:

Ethics, like natural selection, make existence possible. Æsthetics, like sexual selection, make life lovely and wonderful, fill it with new forms, and give it progress, and variety and change. And when we reach the true culture that is our aim, we attain to that perfection of which the saints have dreamed, the perfection of those to whom sin is impossible, not because they make the renunciation of the ascetic, but because they can do everything they wish without hurt to the soul.

This state of “true culture” in which “sin is impossible” is the world that Firbank strived to envision throughout his mature fiction. It also is the world that W. H. Auden referred to when he claimed that Firbank was one of his favorite modern writers because his novels are concerned “with Eden,” and that Firbank himself referred to in a letter to his American publisher when admonishing him not to worry that he had never visited New York City before beginning work on his new novel to be set there (The New Rythum, unfinished at his death), as New York was certain to be transformed into “the New Jerusalem before I have done with it.”

Firbank, whose work has consistently been misread as a mannered form of realism, is in fact a writer of pastoral romance. As such, Firbank vigilantly banned from his work the ethical concerns related to maintaining social well-being and political stability—ideas of justice, fairness, equality, duty, obligation, and responsibility. Calling upon Wilde’s paradigm, we might consider these social concerns to be the evolutionary, communal taste of the species, that which has allowed our species to survive without exterminating itself. Firbank’s pastoral fantasies are concerned with individual tastes related to the beauty of being, which is in the subjective eye of the individual beholder. In Firbank’s idealized pastoral world, in which no one is starving or competing for political rights or material goods, the ethical distinctions of right and wrong are replaced by the æsthetic categories of good and bad taste, while moral judgments are replaced by individual predilections.

Firbank’s novels work to combat sexual discrimination, and they do so by treating issues of sexual desire and identity as matters of individual and cultural taste, rather than as issues of ethical right and wrong. Using Wilde’s analogy comparing ethics and æsthetics to natural and sexual selection, we could say that Firbank’s novels implicitly contend that matters of sexual desire have been misclassified as ethical issues when in fact they are matters of taste.

When Firbank wrote and self-published his novels, discussion of homosexuality was subject to censorship by the British authorities. Firbank evaded the censors by treating sexuality—along with all other conventionally “serious” matters—as a joke. The attitude of his novels is that the characters are just “playing around.” Keep in mind the backdrop of intolerance and oppression that’s being kept at bay, just beyond the work’s pastoral boundary. A “cavalcade of wish-fulfillment” was recognized by Anthony Powell in his sneering description of Firbank’s work (in The Complete Ronald Firbank, 1961). As a political cause, it may be seen as a sustained barrage against the self-satisfied façade of conventional “ethical” behavior that often served as a shield for hatred and bigotry.

Throughout his novels, Firbank’s characters focus upon the pursuit of amorous desires, largely ignoring the conventions of the day. When the status quo is alluded to, it is with a playfully supercilious attitude, as in this fictional meditation on marriage in Prancing Nigger (an unfortunate title that American publishers gave to a novel that Firbank had called “Sorrow in Sunlight”):

In the convivial ground-floor dining-room, “First-Greek-Empire” style, it was hard, at times, to endure such second-rate company, as that of a querulous husband.

Yes, marriage had its dull side, and its drawbacks, still, where would society be (and where morality!) without the married women?

Mrs. Mouth fetched a sigh.

Just at her husband’s back, above the ebony sideboard, hung a Biblical engraving after Rembrandt, Woman Taken in Adultery, the conception of which seemed to her exaggerated and overdone, knowing full well, from previous experience, that there need not, really, be much fuss. … Indeed, there need not be any: but to be Taken like that! A couple of idiots.

Love and death are the two abiding preoccupations of pastoral fiction, the result of its reduction of life to the bare essentials. Not infrequently in Firbank’s fiction, the two are conjoined, as when the Andalusian Cardinal Pirelli, whose sexual tastes are polymorphous, drops dead while on a drunken midnight romp through the cathedral in pursuit of an elusive altar boy who’s driving a hard bargain:

“You’d do the handsome by me, sir; you’d not be mean? … The Fathers only give us texts; you’d be surprised, your Greatness, of the stinginess of some! … You’d run to something better, sir; you’d give me something more substantial?”

“I’ll give you my slipper, child, if you don’t come here!” his Eminence warned him. …

“Olé, your Purpleship!”

It is typical of Firbank’s placidly scandalous fiction that, when there is an instance of what would normally be labeled pedophilia or sexual abuse, it is the conventionally aggrieved party who has the upper hand, for desire puts one at a decided disadvantage. In the same novel, an aristocratic grandmother accounts for her affair with a handsome young footman by explaining:

“He keeps me from thinking (ah perhaps more than I should) of my little grandson. Imagine, Luiza. … Fifteen, white and vivid rose, and ink-black hair.” … And the Marchioness cast a long, penciled eye towards the world-famous Pieta above her head. “Queen of Heaven, defend a weak woman from that!” she besought.

Likewise an aging society belle in Valmouth desires the amorous society of a teenage shepherd boy, but she finds herself repeatedly put off: “I fear he must be cold, or else he’s decadent? Oh, I want to spank the white-walls of his cottage!” Finding herself rebuffed, she resorts to the consolation of her superior class status in its playful and humorous fashion.

Firbank’s fiction reminds us of the fact that not everyone everywhere, and indeed not all societies historically or today, have considered sexual relations between adults and adolescents to be immoral. Of course, we all must live in society and deal with its attendant mores, but Firbank reminds us of the relativity of social standards.

At the end of The Gay Science, Nietzsche predicted the arrival in the world of a playful “spirit” who would prepare the way for a “great seriousness” by making a mockery of the self-righteous ethical system of society. This will be a spirit “who plays … with all that was hitherto called holy, good, untouchable, divine … when it confronts all earthly seriousness so far, all solemnity in gesture, word, tone, eye, morality, and task so far, as if it were their most incarnate and involuntary parody.” Such a spirit was Ronald Firbank, a radically parodic creator far ahead of his time in his revolutionary fictional effort to replace the conventional novel’s focus upon ethics with a liberating and enabling expression of individualist æsthetics. The question remains of whether we have come close enough to Wilde’s “true culture” to begin to appreciate the seriousness of Firbank’s works.

Don Adams, associate professor of English at Florida Atlantic University, is the author of Alternative Paradigms of Literary Realism (2009), which includes a chapter on Ronald Firbank.