Out of the Game

Out of the Game

by Rufus Wainwright

Decca Records

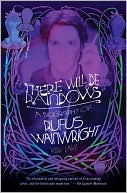

There Will Be Rainbows:A Biography of Rufus Wainwright

There Will Be Rainbows:A Biography of Rufus Wainwright

by Kirk Lake

HarperCollins. 320 pages, $14.99

YOU MAY NOT NEED Kirk Lake’s recent biography of Rufus Wainwright to learn that the singer-songwriter has a penchant for peacocks. “I relate to their brilliance,” Wainwright remarked during a 2007 tour of his Manhattan apartment, replete with peacock feathers on lampshades and a bust of Verdi sitting atop his piano. “I am into excess, and peacocks are the emblem of that, all things luxurious and confusing.”

The colorful album cover to Out of the Game is further proof that the musician is a proud maximalist. Looking like a bored Algernon Moncrieff, he’s poised in a plaid fuchsia sports coat, gazing at his manicure with a skull-topped cane in hand. So many sartorial songs dominate the ditties within: “I got the outfit for the party, but you’ve taken away the invitation,” he gripes in “Rashida” (a possible allusion to actress Rashida Jones and some feud between the two). In “Montauk” he imagines Viva, the daughter he and longtime partner Jörn Weisbrodt are raising with Lorca Cohen (Leonard’s daughter), coming to the couple’s beachside home: “One day you will come to Montauk/ And see your dad wearing a kimono/ And see your other dad pruning roses.” Then, with a lovely dash of desperation: “Hope you won’t turn away and go.”

Lake’s portrait of Wainwright, titled There Will Be Rainbows, is the perfect complement to the Canadian-American’s loud and lavish œuvre and, with its references to Tennyson, Wilde, Kubrick, and Barthes, it is every bit as erudite. His description of one Wainwright album cover as a “character out of an Edward Burne-Jones painting as though lit by Pierre et Gilles” may set a confounded reader on a Google search. Given that Wainwright is the scion of folk-rock’s first family (father Loudon Wainwright III and the late Kate McGarrigle), there are plenty of celebrity vignettes to lighten the mood. There’s Broadway star Betty Buckley fishing a two-year-old Rufus out of the swimming pool at the Chateau Marmont during his family’s stay, and a muse named Penny Arcade (once his father’s mistress) introducing an adolescent Wainwright to Quentin Crisp at a party in the East Village. The author brings to bear the kind of critical eye that’s integral to any serious biography, questioning, for example, the singer’s 2007 decision to recreate Judy Garland’s 1961 performance at Carnegie Hall. So, too, is “Jericho,” with its residue of Elton John, Fleetwood Mac, and other L.A. sounds of the 70’s. There are two love songs for boyfriend Jörn, “Song of You” and “Respectable Dive,” the latter of which is reminiscent of the cowboy lullaby he contributed to the Brokeback Mountain soundtrack. A low note, however, is “Perfect Man,” a potpourri of a composition so diffuse that it moves sideways, then downward. Lake reminds us of the artistic differences between Wainwright and super-producer Jon Brion, who helped to shape his self-titled debut in 1998. Brion would later say: “He wasn’t interested in listening to ideas about simplifying arrangements.” Apparently Wainwright still won’t heed such advice. A more streamlined song, available only through iTunes, is “WWIII,” which features something of a promise: “Don’t bore us/ Get to the chorus/ There’s so much more to come.” Let’s hope Rufus, still le petit prince of pop, is a man of his word. Colin Carman, PhD, will soon serve as a Mayers Fellow at the Huntington Library in 2013.  Out of the Game is Wainwright’s seventh studio album, and his liveliest in years. The title track, in keeping with his self-referential style, alludes not just to the crooner’s age—“I’m out of the game/ I’ve been out for a long time”—but to the fact that the 39-year-old has never hidden his sexuality. Lake quotes his subject as saying: “All of my material is love songs about boys, mostly romantic music about failed love.” If that’s true, failure has never sounded so sweet. Mark Ronson, the retro-soul producer of Adele and the late Amy Winehouse, is on hand to keep Wainwright at the top of his game, up-tempo and “poperatic.” Aided also by Brooklyn’s Dap-Kings and Wilco guitarist Nels Cline (on “Barbara”), this album is just the shot in the arm that Wainwright fans needed after All Days Are Nights: Songs for Lulu, a crestfallen collection of elegies written for his mother, who died of cancer in 2010. There is another tribute to her here: the album closer, “Candles,” refers to McGarrigle’s displeasure with her son’s sexuality back when he was a high-schooler at Millbrook. (Wainwright had been cruising the gay bars of Montreal since he was fourteen.) Lake fills in the biographical blanks by giving us McGarrigle in her own words: “I went to Sacré Coeur and said, ‘Oh what am I going to do?’ and it was like a lightning bolt hit me and said, ‘Do nothing. You don’t try to change a person. It’s not a sickness. Don’t treat it as one.’” With its funereal taps and bagpipes, “Candles” is another kind of epiphany.

Out of the Game is Wainwright’s seventh studio album, and his liveliest in years. The title track, in keeping with his self-referential style, alludes not just to the crooner’s age—“I’m out of the game/ I’ve been out for a long time”—but to the fact that the 39-year-old has never hidden his sexuality. Lake quotes his subject as saying: “All of my material is love songs about boys, mostly romantic music about failed love.” If that’s true, failure has never sounded so sweet. Mark Ronson, the retro-soul producer of Adele and the late Amy Winehouse, is on hand to keep Wainwright at the top of his game, up-tempo and “poperatic.” Aided also by Brooklyn’s Dap-Kings and Wilco guitarist Nels Cline (on “Barbara”), this album is just the shot in the arm that Wainwright fans needed after All Days Are Nights: Songs for Lulu, a crestfallen collection of elegies written for his mother, who died of cancer in 2010. There is another tribute to her here: the album closer, “Candles,” refers to McGarrigle’s displeasure with her son’s sexuality back when he was a high-schooler at Millbrook. (Wainwright had been cruising the gay bars of Montreal since he was fourteen.) Lake fills in the biographical blanks by giving us McGarrigle in her own words: “I went to Sacré Coeur and said, ‘Oh what am I going to do?’ and it was like a lightning bolt hit me and said, ‘Do nothing. You don’t try to change a person. It’s not a sickness. Don’t treat it as one.’” With its funereal taps and bagpipes, “Candles” is another kind of epiphany.