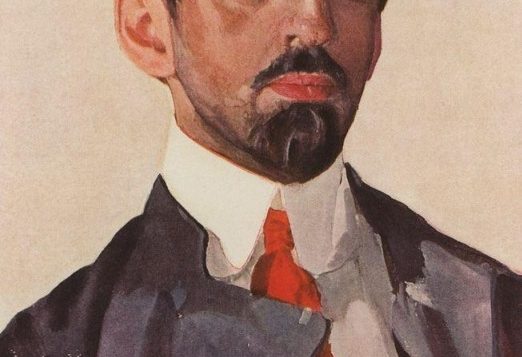

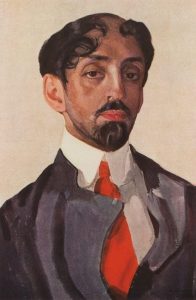

THE YEAR WAS 1928. The Russian poet and diarist Mikhail Kuzmin had just performed his final public reading. He had been invited by a group of students whose enthusiasm was not shared by their institute’s administrators, who had restricted the event and demanded that it not be advertised to the public. Nonetheless, a throng of devoted gay readers showed up, broke the ticket system, and packed the house.

What the ecstatic audience went gaga over was Kuzmin’s unabashedly homoerotic poetry cycle “Forel’ razbivaet led” (“The Trout Breaks through the Ice”), in which righteous queer love triumphs over degenerate, soul-crushing heterosexuality. By flipping the heteronormative narrative so jubilantly, Kuzmin seemed to perform a mysterious lyrical alchemy, causing life to imitate art. The evening came to an almost unbelievably cinematic conclusion, with the proud poet radiating joy from the podium as his adoring fans showered him with bouquets. The public reading, Kuzmin’s flamboyant “verve,” and the rosy finale were tolerated by the authorities, however grudgingly.

During this same period in the West, LGBT creators’ work was not always received with such forebearance. In England, Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness was deemed obscene and banned. Queer-themed theatrical productions were shut down in the U.S., their casts and creators arrested and charged with obscenity and “corrupting the morals of youth.” Even Mae West was arrested and sent to jail for ten days in 1927. The bohemian chic and nascent queer sensibilities of the early Soviet and Western sexual revolutions ran rather parallel courses, arousing ambivalent responses from their respective milieux.

The 1930s marked an abrupt halt to the relative openness of the preceding decade in both the West and in Russia. In the U.S., the next few decades were plagued by even stricter censorship, McCarthy-era fear and isolation, military witch hunts, and the entrapment and arrests of tens of thousands of men seeking men at gay bars in New York City alone. In Russia, Stalin recriminalized “sodomy” (muzhelozhstvo: literally, men lying with men), and between 1933 and 1991 as many as 60,000 men were convicted. Kuzmin would die naturally—just short of Stalin’s Terror, mercifully—before he could realize his dream of a gay literary salon, though there was clearly no shortage of prospective participants.

Historian Dan Healey, in his monumental Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi, notes how “[in]the USA and Europe, we have come to expect an unbroken curve of progress in the construction of full LGBT citizenship.” This may be especially true for the more privileged among us—white, cisgender, male, able-bodied, affluent—who experience citizenship and its rewards more fully. Healey approaches queer life in the Soviet and post-Soviet eras from diverse and fascinating angles, from penal colonies to pornography, developing a compelling argument that Western accusations of Russian homophobia, though well-intentioned, are often paternalistic and uninformed. When Western activists express their outrage, they tend to ignore their own history, the long struggle it took to get where we are, and how this progress remains unevenly distributed. Yana Kirey-Sitnikova, a Russian transfeminist activist and scholar, has expressed frustration over the condescending, colonialist attitudes of Western activists who claim expert knowledge but know nothing of Russian LGBT history or current activism. She rightfully questions how these activists can feel qualified to “save” LGBT Russians while failing to address transphobic violence in their own countries. These Western activists, Kirey-Sitnikova suggests, are generally white cisgender gay men whose concern is evidently the well-being of other white cisgender men.

Indeed, the most visible Western critics of Russia’s “gay propaganda” law, the 2013 act that prohibits any advocacy of LGBT rights, have been affluent white men who’ve enjoyed a linear path to full LGBT citizenship, such as celebrities Ian McKellen and Stephen Fry. Having personally “arrived” at their chosen destinations in life, they engage in what Dan Healey describes as “memoryless” accusations of homophobia—uninformed projections of our own historical memory onto another country on the basis of its citizens’ apparent similarity to “us.” Healey reminds us not only that there is “no common path to a ‘post-homophobic’ society,” but also that our very construct of homophobia is haunted by uniquely Western legacies of European fascism and Nazi persecution. For decades, Western activists effectively mobilized this painful history as a “usable past”—a term Healey borrows from Erik N. Jensen—in the struggle for sexual rights.

While the LGBT victims of the Holocaust have been officially acknowledged and commemorated in the West, similar efforts have not been made by Russian politicians on behalf of the queer victims of the Gulag, whose stories remain largely untold and hidden from history. Conspiracies of silence and notoriously inaccessible archives have contributed to the memorylessness of the Russian LGBT community itself.

In spite of tremendous obstacles and a prevailing Russian notion that LGBT identities were “imported” from the West, it is clear that non-normative sexual and gender practices and identities persisted throughout the Soviet era. Healey advises his readers against viewing Russian LGBT people as “mere victims of widespread homophobia,” instead paying well-deserved attention to their spirit of resilience and creativity. Drawing on the work of Francesca Stella, he recommends a reinterpretation of the “closet” as “a place of safety and possibility” rather than “a burden of inauthenticity and oppression.” Considering Russia’s complicated history with the public and the private—in particular the realities of Soviet communal apartment life, where close quarters and paper-thin walls prevented people from speaking freely—this Russian “closet” might be more aptly called the “kitchen.” Kitchens, in the Soviet era, were the site of intimate gatherings, dissident conversations, art exhibitions, poetry recitations, the exchange of samizdat (hand-typed, illegally distributed) literature, and a myriad of other activities that kept Russian culture alive.

The phenomenon of kitchen culture, while perhaps falling a bit short of the gay literary salon of Mikhail Kuzmin’s dreams, kept hope alive for those individuals who were lucky enough to find one another. Here they gained access to information available nowhere else. And as they shared samizdat texts and worked to conceptualize their identities and circumstances, they forged fiercely loyal friendships. By the 1970s, lesbians were arranging marriages of conveniences with gay men to save them from persecution. Such solidarity with gay men facing years of hard labor could be interpreted as evidence of a more advanced movement than what existed at the time in the U.S., where a sense of gay and lesbian community failed to emerge until the AIDS crisis.

The path of “progress” is multifaceted. And while LGBT activists in the West have set themselves up as the arbiters of other countries’ progressiveness on gay issues—often basing this judgment on their governments’ most recent and newsworthy policy changes—the voices of LGBT people and the details of their lived experience should in the end carry the greatest weight in informing our overall perspective.

Until recently, first-person accounts of queer life in Russia have scarcely been available to the interested Westerner, especially to those lacking proficiency in the Russian language. Two remarkable but as yet underappreciated resources now fill a bit of that void: Sonja Franeta’s Pink Flamingos: 10 Siberian Interviews, published in Russian in 2004 and only finally made available in English in 2017, and Masha Gessen and Joseph Huff-Hannon’s 2014 Gay Propaganda: Russian Love Stories. These important collections of interviews offer captivating glimpses, snapshots of historic moments in the development of the Russian LGBT movement.

Franeta’s interviews of LGBT individuals and couples in Siberia, conducted in 1992 and 1995, capture the hope and uncertainty of the years immediately following the fall of the Soviet Union. Westerners who have known life in rural or conservative communities may feel a certain kinship as they read the experiences of Russians coming to self-awareness and seeking queer connections in such remote areas in the late Soviet and early post-Soviet period. Similarly, the “Russian love stories” of Gay Propaganda, compiled in 2013 as a response to Putin’s “gay propaganda” law and released just in time for the Sochi Olympics, serve to highlight our commonalities. In both collections, we see examples of LGBT people who have carved out a space for themselves and who feel satisfied with their lives. We also see examples of the tragedies and hardships that may befall us in a world of globalized homophobia. To be sure, the Russian government’s complicity in the imprisonment, torture, and murder of LGBT people in the Chechen Republic absolutely demands worldwide condemnation—as does the United States’ complicity in police brutality against black people and the pervasive violence faced by trans women of color.

For LGBT people in the West, trying to understand LGBT life in Russia can be a bit like looking at an old black-and-white photograph: it feels a world away from our reality. When the image is colorized, however, it suddenly becomes comprehensible, relatable. When we base our perceptions on the black-and-white of news headlines from largely Western sources, we feel similarly estranged. The deeply personal interviews of Pink Flamingosand Gay Propaganda, and the historical insights of Healey’s Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi, add color and life to the widely held perception of Russia as a bleak wasteland devoid of queer possibilities. Russian LGBT individuals do not deserve to be the objects of Western pity. On the contrary, they are fully capable subjects whose acts of agency in the present are creating a usable past that will come to fruition in its own time.

“The Trout Breaks Through the Ice: How a Forgotten Poet Became the Hero of the Gogol Center”: thus read a Russian news headline, referring to a 2017 theatrical production staged at the Gogol Center in Moscow. The play is based on what had turned out to be Mikhail Kuzmin’s final volume of poetry. In 1936, he died of pneumonia in relative obscurity, narrowly escaping Stalin’s Great Terror, which claimed the lives of so many of his contemporaries—including his lover of more than twenty years, Yuri Yurkun. In spite of Kuzmin’s significant contributions to the Silver Age of Russian Poetry, his passing was afforded little more than a footnote in the press, his name misspelled. Under Soviet censorship, his work all but disappeared, surviving in émigré communities and eventually returning to Russia in samizdatpublications.

This triumphant re-emergence of The Trout attracted audiences as enthusiastic as Kuzmin’s in 1928, and clearly did not go unnoticed by the authorities. In June 2017, the Russian government contributed a Bulgakov-esque, plot- and fact-twisting turn of the screw by arresting the Gogol Center directors. The pretext was that they had failed to perform a fifteen-show run of A Midsummer Night’s Dreamas claimed—in spite of the testimony of reviewers and theatergoers. However, the timing of the raid is interesting, coming as it did in the midst of the Gogol Center’s limited run of The Trout. It seems clear that the authorities’ real target was the work derived from Mikhail Kuzmin, the immortal face of Russia’s gay history. Vladimir Medinsky, head of Russia’s decidedly Orwellian Cultural Ministry, has announced that he wants to promote “Russia’s ‘traditional values’ over ‘multiculturalism.’”

The stage production of The Trout was the latest installment in a five-production cycle, the others based on works by (heterosexual) poets held in higher regard: Boris Pasternak, Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, and Vladimir Mayakovsky. Alongside these names, Kuzmin stands out as a marginal figure—in terms not only of his queerness, but also his lesser critical success and legacy. But the tide may be turning, if Russian news articles with titles declaring him a hero are any indication. The inclusion of The Troutin this cycle is a testament to the robustness and enduring novelty of Kuzmin’s work—and its central metaphor, a testament to the persistence of the Russian LGBT soul.

Stephan Nance, a singer-songwriter and scholar from Eugene, Oregon, holds a degree in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies from the U. of Oregon. They maintain a website at www.stephannance.com.