Editor’s Note: The following is by a grant recipient in a program launched in 2022 by The G&LR, our Writers and Artists Grant, which was awarded to three recipients in 2023. The purpose of this grant is to assist advanced students engaged in LGBT-related research, and awardees are expected to produce an article for this magazine as part of their project. This is the second of three articles from last year’s recipients.

FROM THE STONEWALL RIOTS of 1969 to the recent raid of a Seattle-based gay bar called the Cuff Complex, police harassment of LGBT+ people in bars and nightclubs forms an important part of our history. Unlike New York City or Seattle, a city like San Antonio, Texas—mid-sized, Southern, and largely Latinx—tends to be overlooked in the history books. And yet, San Antonio was at the center of an important legal battle between the U.S. military and a gay discothèque called San Antonio Country in 1973 and ’74. Indeed this court case provides a lens through which we can examine how gay people in this era survived in the face of persecution by outside forces.*

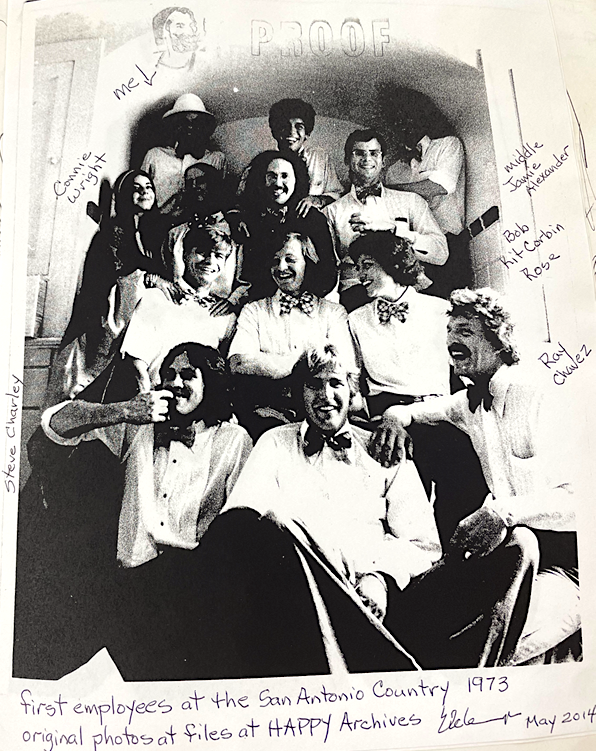

In the post-Stonewall Gay Liberation era of the 1970s, a major change took place in the lives of LGBT+ San Antonians with the opening of San Antonio Country, commonly known as the SA Country, in April 1973. The club was founded by the developer Arthur “Hap” Veltman along with the bar’s manager and a close friend of Veltman, Gene Elder. Veltman was a well-known entrepreneur who developed the first restaurant facing San Antonio’s iconic Riverwalk. Up to that time, according to Elder in a 1993 oral history: “the gay bars in San Antonio were very small holes in the wall.” Another thing that distinguished the SA Country was the openness with which the bar publicized its sexual orientation. Perhaps for this reason, the bar was raided almost immediately by both the Military Police (MPs) and the local vice squad, and it was placed on the military’s off-limits list.

For context, San Antonio is known as a “military city” due to the large population of active duty military and veterans who live in the city. Historian Melissa Gohlke remarked that being placed on the off-limits list was sometimes akin to free advertising and enabled LGBT+ servicemembers to know where the local gay bars were located, because they were often posted in barracks for the servicemembers to see. Conversely, placement on this list also meant harassment and increased risk for service members who frequented these bars.

The Stonewall Riots had provided one model of resistance, but the response this time was different. Veltman and Elder, with the help of their lawyers, challenged this injustice in military court. This court case is legendary in San Antonio queer history and resulted in several published articles and oral histories, a documentary, and even a play. In these retellings of the landmark court case, there’s a standard narrative that the queer community of San Antonio triumphed over the homophobic military. This David and Goliath scenario has often drawn comparisons to the Stonewall riots and painted Veltman and Elder as champions of LGBT+ rights.

However, these narratives conceal important facts about LGBT+ life in San Antonio in the early 1970s. While I’m not here to challenge the belief that Veltman and Elder were instrumental in shaping San Antonio queer life or to diminish the importance of the legal battle and its outcome, I would like to offer a more nuanced account of the court case and a more holistic approach to this contentious time (1973–’74) in the history of LGBT+ life in Texas. I hope to elucidate some of the complexity of queer urban politics in South Texas and, in doing so, to broaden our understanding of a larger swath of that life: that of Southern, Black and brown, and noncoastal urban queer experiences in the era between Stonewall (1969) and the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s.

The court case was a small part of a long history of harassment by MPs after establishments were placed on the U.S. military’s off-limits list. After the SA Country was placed on this list and police harassment began, Veltman and Elder challenged this injustice in a military tribunal. In doing so, they fought for LGBT+ rights and were ultimately successful in curtailing both the military’s efforts to put the SA Country on the off-limits list and the military raids and harassment of the SA Country. As Gene Elder says in his unpublished autobiography: “Our lawyers all got together and began the magic ritual of paper shuffling that lawyers do and the next thing we knew the whole business was dropped and never spoken of again. The military eventually dropped their efforts to put us ‘off limits.’” Yet this narrative by Elder, along with articles in gay publications, documentaries, and oral histories, don’t capture the complexity of the tensions between the rival parties. During this contentious court case, Veltman, Elder, and their lawyers adopted the strategy of centering their case on the violation of their economic rights as upstanding businessmen rather than the rights of LGBT+ people. In this way, they oscillated between defending people’s right to be gay and distancing themselves from the gayness of their clientele. Finally, the SA Country went to multiple military tribunals, and while the harassment of the club abated over time, it never went away completely. The military tribunal transcrips reveal that Veltman, Elder, and their lawyers argued that the placement of the SA Country on the off-limits list, and the harassment and mistreatment by the MPs, represented an infringement of their economic rights without reference to the sexual orientation of their clientele. To make this claim, they emphasized that they had made a “sizable investment” in the club, while placement on the off-limits list harmed their ability to stay in business. In addition, Veltman and Elder tried to demonstrate that they had ties to reputable business and publishing organizations. For example, in a letter to his lawyers to be passed to the military tribunal, Veltman wrote: “[The] San Antonio Country does not hold itself out as a homosexual bar, or as a gay bar. It has been offered membership in the San Antonio Chamber of Commerce, and the Texas Restaurant Association, which membership it has under consideration. It is anticipated that it will be listed in Texas Monthly as a San Antonio discothèque, which is open to all persons of legal age.” Part of their strategy was to present themselves as successful entrepreneurs whose establishment played an important economic role in San Antonio. An important element of Veltman’s letter to his lawyers was the final line, “open to all persons of legal age,” which subtly hinted that the SA Country was a space for everyone, including LGBT+ people. In fact, later that year (in October 1973), Elder gave an interview to The Trinitonian proclaiming that the SA Country isn’t just a gay bar, but instead “a place anyone can feel comfortable in.” In doing so, they engaged in a tactic of respectability politics that allowed them to continue operating a known gay bar while appeasing the U.S. military. During another military tribunal, on July 6, 1973, Veltman stated the following: “To correct any situation that the military may deem harmful to military personnel, I will evict anyone from the premises who any competent military authority designates as a homosexual or undesirable in any way. All I ask is that the military in turn indemnify me for any liability I may incur in doing so. I do not think any businessman could be asked more.” This statement demonstrates three core elements in the strategy that Veltman and Elder used to challenge police harassment: 1) distancing themselves from the LGBT+ community and from their own sexuality as gay men; 2) acknowledging the “harm” of homosexuality on young, impressionable, and largely male service members; and 3) reconstituting themselves as “businessmen” to claim their place as economic actors. While Veltman’s statement sounds homophobic to our ears, a more generous reading might acknowledge that they were playing into a politics of respectability that would enable them to continue operating their popular gay disco. It should be noted that neither Veltman nor Elder is alive to speak for himself. (Veltman died in 1987, Elder in 2019.) However, I had the opportunity to speak to Elder in 2014. Even then, a few years before his death, he was an outspoken advocate for social justice who had fought for equal rights for decades and created the Happy GLBT Archive dedicated to the preservation of queer history. Their statements in the mid-1970s must be understood in the context of the complexity of survival in an era of homophobic persecution. While Elder and Veltman superficially acquiesced to the demands of the military ban on “known homosexuals” from their bar, this never transpired, and the SA Country remained a widely popular gay bar for many years after this court case. Yet despite its continued operation as an LGBT+ space, it was not simply ignored by the U.S. military or the city’s vice squad. As a former employee of Veltman stated in an interview in Noi Mahoney’s 2019 documentary Hap Veltman’s San Antonio Country: “He would fight that [being on the military’s banned list]all throughout the time he was alive. It was a constant … they would put us on the banned list and then he would go over there and fight to get the military people to be able to come into his bar, and then they would put us on the banned list again and he would go back and fight it. It was a constant battle.” Mahoney’s documentary captures a particularly violent night of harassment in December 1973 when MPs beat and arrested several gay patrons and threatened Elder. The documentary discusses the court case as a byproduct of this harassment. However, this chronology does not accurately reflect the timeline of events, as the court cases date to the summer of 1973. In an oral history conducted in 1993, Elder discussed the raid of December 1973 and read from the military tribunal that took place six months earlier. In another example of this re-ordering of history, in an interview published on October 26, 1973, Elder states: “The military … tried to have it [the SA Country]put off-limits to military personnel. After a hearing by military officials, however, the issue was dropped.” Yet on October 30, 1973, the U.S. military placed SA Country back on its off-limits list and sent a letter to Gene Elder stating that “you have failed to comply with our agreement … by allowing overt acts between male individuals in your establishment.” An interviewee in Mahoney’s documentary states that he began going to the SA Country in 1977, and he recalled the U.S. military coming through and checking IDs in search of military personnel. Clearly harassment by the military and the San Antonio Police Department did not end in 1973. In fact, the story of the SA Country ends with another homophobic legal challenge. In 1980, the Valero Company filed a lawsuit to close the SA Country. In an article titled “Male Hookers Infest Downtown,” a local anti-LGBT+ advocate stated: “Valero Energy Corp. has filed suit against the … San Antonio Country. … Valero alleges the defendants permitted the use of sidewalks, streets, parking lots and other property to be used for homosexual solicitation.” This legal battle ended in the closing of the SA Country and the leveling of the building to create a parking lot. This closure led Veltman to open Bonham Exchange (with the forced payout money from Valero), a nightclub still in operation as of this writing.

Among the predominantly white, gay, and male voices of the LGBT+ archive in the 1970s, the opening of the SA Country changed San Antonio’s gay scene dramatically. For these men, San Antonio was a closeted and conservative city, even compared to other Texas cities such as Houston and Austin, which were considered to have more open gay scenes. One interviewee in Mahoney’s documentary described San Antonio as “pretty provincial” when compared to Houston. Yet the SA Country had a profound impact on the city’s gay scene. The value of having queer elders discuss their unique experiences is priceless. We as a community have tragically lost too many queer voices from homophobic violence, the hiv/aids epidemic, and poverty. However, upon watching Noi Mahoney’s documentary, I grew uncomfortable with its predominantly Anglo and gay male perspective. San Antonio has been a majority Hispanic city since at least the 1970s. However, few Latinx individuals were interviewed, with one notable exception: Ray Chavez, a well-known gay icon in San Antonio. Interviewees described San Antonio as conservative due to the influence of religious “Hispanics.” One interviewee described San Antonio in the following way: “Everything was very hush-hush and low key, and I think, again, that’s because you have a Hispanic community, a Catholic community, and a heavily military presence. And all three are conservative, closeted communities. And it did set San Antonio back in things like civil rights marches and parades … especially when AIDS came along.” This narrative that San Antonio’s queer community was particularly closeted and conservative because of “Hispanics” is a recurring theme in the documentary. The conservative influence of the U.S. military is also emphasized. As another interviewee stated: “The demographics of this place have always been very strange, you know, with the military and the Hispanics.” The belief expressed in these quotations that the U.S.-based Latinx community is more conservative on LGBT+ rights than other populations does not square with my own experience. As a mixed-race (half-Mexican-American and half Anglo) queer man, I have come out to both white and brown family members with equal parts animosity and acceptance. While not explicitly racist, the viewpoint that Hispanics are more socially conservative, religious, and anti-gay than their Anglo counterparts promotes a narrative that the Latinx community is backward and closed-minded. There’s also a belief that Latinos are more misogynistic than white men—another painful and racially charged stereotype about a very heterogeneous community. Of course, heterosexist patriarchy is alive and well in both Anglo and Latinx communities. Accounts of the SA Country vary in its purported racial and gender diversity. For many interviewees, the SA Country welcomed Black and Latinx San Antonians. Unfortunately, these narratives rely on the oral histories from almost exclusively white and largely male elders. Photographic evidence does document Black and Brown performers and staff at the SA Country, yet the extent to which this was reflected in the clientele requires additional verification from queer elders of color who were active in the LGBT+ scene at that time. The dearth of perspectives from queer people of color in the archive in San Antonio speaks to a broader erasure in the way that our histories are told and shared. The racialized language many use to describe San Antonio’s gay scene not only regurgitates harmful stereotypes about the supposed conservativism of San Antonio’s Hispanic community, but also extends the erasure of Latinx queer spaces and renders invisible queer Latinx communities. The SA Country provided a place that was not just a bar but a focal point for the disparate members of this community to find a (relatively) safe space to be together and to be themselves, yet these important limitations remain. The qualifier “relatively” is needed because, even after the 1973 ruling, harassment by both the vice squad and the U.S. military continued, albeit somewhat abated. As late as 1987, there were raids on a lesbian bar called the Jezebel that were perpetrated by the U.S. military. The historic and recent raids of queer spaces in San Antonio, and the diverse tactics LGBT+ activists have employed to challenge these injustices, are an important window into understanding the day-to-day negotiations of queer survival in the past and present. ______________________ * This article is based on archival research at the University of Texas San Antonio’s Special Collections and the Happy Foundation GLBT Archives, and on informal conversations with both LGBT historians and San Antonian elders.

Complicating the Narrative

Continued Threats and Harassment

Racial Erasure

Lucas Belury (he/him/el), a doctoral candidate in geography at the University of Arizona, has published articles on urban informality, environmental justice, and race equity.