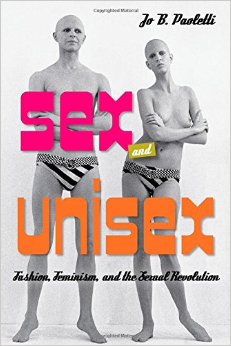

Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism, and the Sexual Revolution

Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism, and the Sexual Revolution

by Jo B. Paoletti

Indiana. 216 pages, $25.

THE AUTHOR of Sex and Unisex begins by quoting Republican candidate Rick Santorum from 2008: “You’re a liberal or a conservative in America if you think the ’60s were a good thing or not. If the ‘60s was a good thing, you’re left. If you think it was a bad thing, you’re right.” Jo B. Paoletti takes up this proposition by analyzing the clothing, hairstyles, and fashionable body types of the 1960s and early ’70s. Her major themes include: the “unisex” look as an expression of gender equality; the “peacock revolution” among males as æsthetic rebellion against macho conformity; and short skirts on young women as a sign of youth, sexual assertiveness, and independence from adult authority.

Anyone who regards an interest in fashion as a trivial pursuit is likely to lose patience with Paoletti’s focus on fabric, design, and marketing. Although the book is a paperback, it includes enough illustrations to be classified as a coffee-table book. The author has written two earlier works on the sociology of fashion: Changes in the Masculine Image in the United States, 1880-1910 (her doctoral thesis, 1980) and Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America (2012).

One widespread current belief that Paoletti debunks is that girls and women of the ’60s were not allowed to wear trousers until some brave, butch woman paved the way for the rest of us. Contemporary images from mail-order and pattern catalogues show identical “play clothes” for boys and girls under the age of puberty. Little girls, especially in the U.S., could wear Western-style shirts with jeans and even a holster with a toy gun, and this look was socially acceptable all through the ’50s and ’60s. There was a practical reason for advertising unisex clothing for the under-twelve set: families of the Baby Boom tended to be large, so parents appreciated sturdy clothes that could be passed down from brother to sister or vice versa. Pants for adult women were also widely accepted in the right social context. Images of Marilyn Monroe posing in snug “pedal-pushers” and Lucille Ball camping or gardening in jeans were seen as amusing or titillating but not really transgressive. At the time, these images presumably showed how famous women looked in private, in “casual dress.”

Most schools, religious institutions, and offices had a strict dress code that demanded gender-segregated clothing from kindergarten on: dresses for little ladies, shirts and dress pants for little gentlemen. The advent of jeans as a unisex uniform for teenagers in general was much deplored by authority figures because a preference for the denim pants of working men was seen as a rejection of white-collar respectability and a refusal to grow up.

More extreme than the rising hemlines of women’s skirts or the arrival of the pantsuit for women was the revolution in men’s fashion. Explains Paoletti: “The vivid, revolutionary nature of young men’s clothing in this period is evidence that the time was ripe for a rejection of the masculine mystique along the same lines of second-wave feminism.” These changes she describes as a “Romantic revival (velvet jackets and flowing shirts)” of European fashions that also embraced styles borrowed from Africa and Asia (the Nehru collar, the dashiki, the use of beads and fringe). The variety of styles for men that replaced the 1950s male uniform of the business suit provoked homophobic outrage as well as predictions that men would never wear ties again.

We know now that neither industrial capitalism nor “the organization man” disappeared after 1970, and the most flamboyant clothing styles for men in the “Carnaby Street” era were more popular with rock stars and their fans than with men in more conventional jobs. Some things, however, really changed: male fashions remain fairly anarchic today by mid-20th-century standards. It is now widely acknowledged that the most influential clothing designers of this era were gay men—this at a time when fathers threatened to disown their long-haired sons for looking like “sissies.”

Paoletti devotes a whole chapter to court cases in which “the Establishment,” as it was called, tried to police the appearance of the young and trendy. Most of these cases focused on the length of men’s hair at school or on the job. For many employers, school administrators, and military brass, long hair on men represented an existential threat to civilization. The author traces controversial fashions for young American men back to the early-1960s and the “British invasion” in fashion and music, but she doesn’t explicitly connect it to a British upper-class, homoerotic public-school tradition.

The hysterical reaction to changes in young men’s appearance in the 1960s shows that something deep and visceral was going on, fueling the rage of fathers vis-à-vis their necklace-wearing, mop-top sons. The threat of “perverse” sexuality (non-heterosexual and/or non-monogamous) was undoubtedly the elephant in the room.

As the author shows, the various revolutions that began in the 1960s are still unfinished. Neither short skirts nor pants nor a relative lack of underwear have “liberated” women from gender-based discrimination, and the “peacock revolution” didn’t pave the way for men in general to wear androgynous styles and bright colors on a daily basis. However, the philosophical significance of physical appearance, as shown in this book, seems undeniable. Paoletti didn’t invent the sociological study of fashion, but she has made an impressive contribution to it.

Jean Roberta is a widely published writer based in Regina, Saskatchewan.