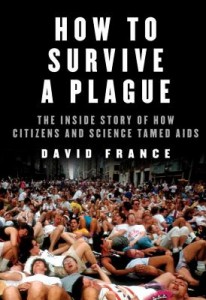

How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS

How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS

by David France

Knopf. 624 pages, $30.

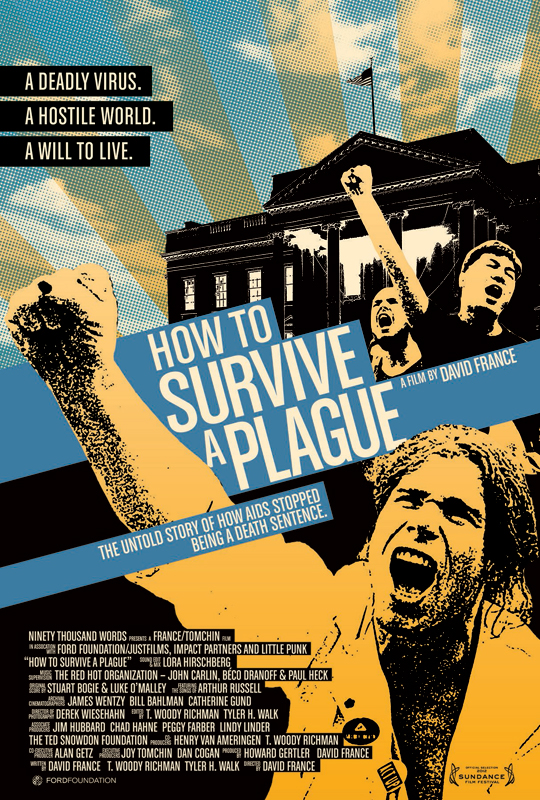

DAVID FRANCE’S HISTORY of AIDS opens with a memorial service for Spencer Cox, an ACT UP activist, to whom we come back in the epilogue. In between are approximately thirteen years of Hell. Although How to Survive a Plague pretty much follows the plot of the documentary film he released four years ago with the same title, the difference between the two is enormous. When the film came out, this reviewer wondered if a book would not give us more nuance, more insight into what people were really thinking in those ACT UP meetings we saw on screen. Well, here is the answer to that wish.

The book is much more complex than the film. Not only do we learn more about what happened, but it’s more dramatic and gripping. Watching the documentary, we were passive onlookers; reading the book, we enter into the minds and hearts of characters in a way the camera cannot. Indeed, France uses the techniques of the epic 19th-century novel so well that the line between fiction and nonfiction blurs. By following a set of characters over the years—their health, love affairs, hopes, fears, relationships—we experience this epoch with an intimacy that the film could not convey.

The characters we follow are mostly the same people the film concentrated on, with some additions: Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz (co-authors of a safe-sex manual early in the epidemic), Dr. Joseph Sonnabend (a gay physician in Greenwich Village), Peter Staley (a closeted Wall Street bond trader who joins ACT UP after turning positive), Mark Harrington (a Harvard graduate who becomes ACT UP’s expert in the science of the disease), Bob Rafsky (a divorced father who handles ACT UP’s public relations), Bob Bahlman, Spencer Cox, Garance Franke-Ruta, Jim Eigo, Gregg Bordowitz, David Barr, and others. In the background are the more public figures who figured in the epidemic: Ryan White, Rock Hudson, Robert Gallo, Ronald Reagan, Anthony Fauci, Larry Kramer.

The story begins, however, with Charles Ortleb, the founder of The New York Native, a gay newspaper that was the only place to find news about AIDS in the early days, and an article he published by Kramer in March 1983 headlined “1,112 And Counting.” (Read it on-line to get a sense of what was going on; it retains all its power.) Kramer convened a meeting in his apartment that became the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. When they no longer welcomed his presence, he gave a speech at the Gay and Lesbian Center one night (subbing, in one of those details that make France’s book so well reported, for the writer Nora Ephron, who had the flu) that turned out to be the founding of ACT UP.

Ortleb, in France’s rendition, soon became Captain Ahab going down with a ship called African Swine Flu after he decided that HIV was not the cause of AIDS, which cost him his whole publishing empire. Kramer, in this version, comes off as a temperamental Prospero, “the Cicero of words” who created ACT UP and then became as much of a liability as an asset. Ortleb and Kramer would, I assume, beg to differ. (Ortleb, in fact, has written an eleven-page letter to the head of Knopf that not only protests France’s version of his days at The Native but calls France a “covetous sociopath.” And both Kramer and Ortleb have written, or are writing, their own books.*) Whatever the truth, one senses that scores are being settled here. Ortleb is dispatched early on, while Kramer continues coming in from his house in the country, where he’s at work on a play, to attend an ACT UP meeting and scream at the youngsters for bickering over trivial political issues whose sponsors eventually hijacked the organization with a vengeance that finally drove the real heroes of this story out of the group.

Some of the scenes France describes he witnessed personally, and it’s the interweaving of reportage with personal witness, the shift from third to first person, that makes How to Survive a Plague all the more riveting. France was so terrified of contracting the disease that was killing everyone around him (is that a bruise or KS?) that at one point he fled to Nicaragua to escape the nightmare by reporting on another war. But he came back, and the most moving passages in the book are descriptions of France’s private life. When his gay neighbor in the East Village died, France bought the apartment in part to preserve the legacy of a black-white relationship that ended when both lovers died of the plague—a legacy that included the outline of the man who lay dead on the floor for a week before being discovered. Then there’s the vigil France kept when his lover David Gould was dying in a New York hospital. Each night France asked the nurse if the doctor had been in to see him, and each night the nurses would all say the same thing: the doctor had come, but France had missed him. But when France decided to stay there all night, still nobody came. So, after his lover died, France tracked down the doctor. The physician, who first appears in the book as one of the good guys, an expert in the treatment of KS, confessed to France that he had indeed gone to the hospital every night—“after the opera”—but only to sign in and leave without visiting anyone. It’s like something out of Joseph Conrad. In talking to the doctor, France realized that he had, in a way, gone mad. A physician who’d begun with the best of intentions had become so burned out from watching his patients die that France ends the scene without judging him—a touch that does so much more than any score-settling might have.

Most of the time, however, France is like Dante taking us on a tour of the Inferno; he makes us care for the people whose conduct he admired and dislike those whose behavior he found reprehensible. And it is an Inferno that’s being portrayed here: these people are in hell, a hell that lasted from 1983 to 1996, more or less. This raises a problem endemic to all journalism, especially when it aspires to history: that we are subject to the writer’s view of things. All historians, obviously, make judgments. And all historians revise—which means: stay tuned for further accounts. Just before France’s book came out, the first big book about AIDS, And the Band Played On (1987), was in the news because it turns out that Patient Zero, the Air Canada flight attendant whom Randy Shilts blamed for the initial spread of the plague, was not the Typhoid Mary of AIDS, after all. Shilts’ publisher simply thought the story of Gaetan Dugas would sell books—a charge France supports by quoting a confession of regret from Shilts’ editor (a confession Ortleb says in his letter that he can’t imagine that editor making). Journalists make judgments and write for dramatic effect, and nothing is more dramatic than a record of who did what during a war, which is what the plague years were. As with Dante devising punishments for his enemies in hell, one senses in How to Survive a Plague another writer doing much the same.

The heroes in both the book and the film are the little band who devoted themselves to finding drugs that would save lives. In both versions we learn that what really made a difference in the fight against AIDS was not so much ACT UP and its “zaps” as it was the work of a small segment of the organization, the Treatment Action Group (TAG), which the rest of the group finally accused of being elitist—which they were, inevitably—heads above the rest in intelligence and determination. It’s TAG’s battle with the medical establishment that forms the spine of both book and film. TAG’s goal was to get “drugs into bodies” that would stop the opportunistic infections that were killing people. The scientists wanted to discover the cause of AIDS—a struggle that produces in this book its own villains and heroes, particularly in the competition between the American scientist Robert Gallo (whom France describes as having “raptorial eyes and a bent nose”—you see what I mean about viewpoint) and Luc Montagnier, the French scientist who isolated HIV first.

Anthony Fauci, the head of the NIH’s response to AIDS (until a separate AIDS czar was finally appointed in the Bush Senior administration), wanted to run drug trials according to scientific protocols; TAG wanted to stop the blindness, pneumonia, Kaposi’s sarcoma, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, and wasting disease that were killing people while scientists were working in the lab. Fauci wanted to give half the people in his drug trials a placebo, which TAG argued was immoral. Nothing gives us a sense of the semi-controlled panic in which people were leading their lives like the joy that many people expressed when AZT came on the scene—until people realized that AZT was not the cure; or the sense of relief when TAG finally got the NIH to concede that prophylactic use of a drug called Bactrim prevented the pneumonia; or the frenzy over Compound Q, a drug touted by a West Coast activist who ended up crossing swords with TAG.

Mathilde Krim, on the other hand, is the Lady Bountiful who keeps Joseph Sonnabend going even when the endless care he gives his patients is bankrupting him and plunging him into depression. Krim, a Swiss scientist married to a Hollywood producer, not only floats Sonnabend financially but redoes his apartment and gets rid of his cat, before going on to create amfAR, the American Foundation for AIDS Research. Sonnabend is another hero—not just for his devotion to his patients but for the prescience of his view that it would take more than one mode of attack to defeat AIDS, namely the combination therapy that finally provided a way out.

Historians, a historian once told me, have forgotten the power of the anecdote. Not France. From Krim’s “first, we threw out the cat!” to Kramer’s taking his first dose of AZT in Barbra Streisand’s guest bathroom while trying to write a screenplay of The Normal Heart, this book is full of vivid, intimate detail. And France is also good at directing the big scene: the speech at the San Francisco AIDS conference, where Peter Staley turned things around by asking the audience of frightened scientists to stand up if they disagreed with the U.S. government’s policy of denying visitors with HIV entrance into the U.S., and they all did. (“You can all now consider yourselves members of ACT UP,” he told them); or the mêlée in which ACT UP “royalty” Tim Bailey’s coffin is bounced around in front of the Capitol during a struggle with the police over ACT UP’s attempt to stage his funeral there—a scene that made this reader laugh out loud. That’s the effect of France’s book: you’ll laugh, you’ll cry, you’ll scream at people who have long since disappeared—people like the manager of the law firm at which Michael Callen temped who fired Callen because his HIV-positive presence made the lawyers uncomfortable; or the tenants in the building in which Sonnabend had his office who wanted to evict him because they didn’t like people with AIDS walking through the lobby; or the nameless hospital workers who left the food trays of people with AIDS in the hall and, like the shell-shocked doctor, never entered their rooms.

To read this book is to be re-infuriated—by the food trays, the columnists who called for a quarantine, even the gay men who considered the disease a right-wing conspiracy to take away their newfound sexual freedom. The public’s views of homosexuals that were common at the time are even harder to take. When the Reagans came to New York to commemorate the hundredth year of France’s gift of the Statue of Liberty to the U.S., Bob Hope told a joke before the 300 guests that went: “Did you hear that Lady Liberty has AIDS? Nobody knows if she got it from the mouth of the Hudson or the Staten Island ferry.” One would like to imagine the audience sitting there like the theater-goers at “Springtime for Hitler.” Instead, France writes, “The president threw his head back and roared.”

In this maelstrom of emotion, of good and bad behavior, the greatest irony, as in the film, is that the end of AIDS came about because of a scientist named Emilio Emini, who was working on HIV at Merck, not to save friends (he didn’t know anyone with AIDS) but, in his word, for the “fun” of science. (When activists introduced him later on to some patients, France writes, it “affected him profoundly.”) This happened after the first scientist in charge of Merck’s search for an HIV drug decided to change his flight home from England and was blown up in the Pan American jet over Lockerbie, Scotland. The way a Libyan terrorist’s bomb slowed the response to AIDS is another of the many ironies in this suspenseful saga. The story of the plague could have turned out so differently than it did. Had Mark Harrington not decided one day to have his swollen lymph node biopsied (which proved that HIV was not just in the bloodstream but hiding out in other places in the body), had the viral load of Patient 142 (the only person in Merck’s trial on whom the HIV drug’s effect did not wear off) not remained low, had people like Larry Kramer not waited to take AZT when he did, the plague might have turned out differently. Yet one may still ask a question the film raised: Was ACT UP necessary? Or was it TAG’s work with the doctors, drug companies, and the NIH that changed medicine and got the job done? Peter Staley’s answer is that just knowing he had the demonstrators to put on the street made his job of negotiating with the scientists and drug companies easier: what Kramer called the “good cop, bad cop” method.

After the discovery of the combination therapy that not only “tamed” AIDS but led to what was called “the Lazarus Effect,” in which previously dying people got up from their hospital beds and walked away, there was a terrible collapse suffered by the activists at the center of the struggle. In the film we have their personal testimony. In the book we learn that after losing out to Mark Harrington in a “power struggle” at TAG, Peter Staley went on to abuse crystal meth for two years, Spencer Cox stopped taking his meds and effectively killed himself, and Derek Link was revealed not to be HIV-positive, whereupon the others stopped speaking to him. (The shared conviction that everyone in TAG was dying was a big source of its camaraderie.) Reading this book on a cozy December night in bed under the covers, far from the hospital rooms in which so many people died, is to feel the uncanny, arbitrary nature of fate. When a friend heard that I was reading this book, a man who remembers visiting people in the hospital whose room no one else would enter, he asked: “Why? Why would you want to—to go back to something so painful?”

For one thing, curiosity. For anyone living in New York at the time who had nothing to do with ACT UP, How to Survive a Plague tells you what was going on at all those meetings and demonstrations that you didn’t attend. France’s book may make the reader feel like a Frenchman who did not take part in the Resistance. Yet reading this book is strangely cathartic, because this is where, paradoxically, gay life was occurring in those years: in the deepest shadow of death.

Older gay men complain that the current generation knows nothing about this story, and has no interest in it. But why should they? What does it have to do with gay life—besides posing a danger to the sexually active? On the one hand, you could argue that the plague was irrelevant to being gay. It was the story of a virus, nothing more. Scientists, France notes, do not even consider a virus a form of life; it is “on the edge of life.” A virus has nothing to do with the issues of being homosexual: how to attach oneself to another human being; how to live a full life; what happens when you walk into a bar, or go online, or undress in the presence of another person, with all the hopes and needs for affection that this entails. AIDS simply hijacked gay life momentarily, sucked all the air out of the room, destroyed individual people and a way of life, and left nothing behind.

On the other hand, you could argue that it intersected with every gay issue: homophobia, promiscuity, the closet. (Today’s married, child-rearing generation is a reaction to it, one suspects.) And the way the people in this book fought back is something that has been added to gay identity. Larry Kramer claimed that it was the greatest thing gay people had done in this country. It showed that gay people had enormous willpower, backbone, and determination—that they were not “sissies,” after all.

Andrew Holleran is the author of Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited.