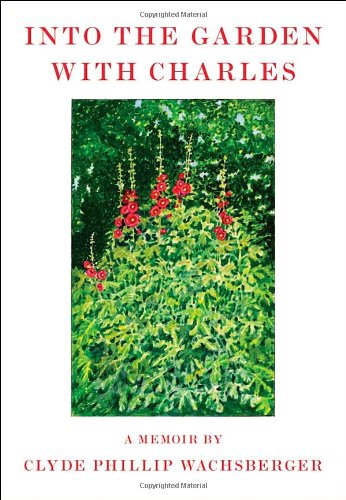

Into the Garden with Charles: A Memoir

Into the Garden with Charles: A Memoir

by Clyde Phillip Wachsberger

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

210 pages, $28.

CLYDE (“SKIPPER”) Wachsberger had no interest in baseball as a boy but was happy to go with his father to nurseries, and he so loved peonies that after the real ones outside his house had bloomed, he would make more out of Kleenex painted with his mother’s lipstick. Even as a grown-up in Manhattan, what he really wanted was a garden of his own—and someone to garden with. At a time when gay men in New York were rushing to the bars, baths, and backrooms, Wachsberger believed in monogamy. So, he finally placed an ad in the Village Voice personals section—and to his surprise the newspaper called him to come down and collect the over 300 replies. But after methodically meeting the respondents, one by one, he found that the only thing he had in common with them was a desire for a monogamous partner. So, in 1983, at age 38, he moved to the north shore of Long Island, where his gay sister was already living with her partner in a town called Orient, and bought a 300-year-old-house with enough property for him to realize a dream he’d had since childhood: a garden of his own.

Twelve years later, he had reconciled himself to solitude; but then one day he saw a personal ad in the local paper and answered it. The ad proved to have been written by a man in Manhattan who wondered why someone from Orient was calling him, since he had placed his ad in The New York Native. It turned out the Long Island paper had simply lifted a bunch of personals from Manhattan’s gay newspaper to supplement its own listings. No matter; a trip to New York to meet proved so successful that the following weekend a tall Southerner named Charles Dean came out to Orient, where, though it was a snowy winter weekend, things went so well that Skipper invited Charles to get into the bathtub with him. (“It had been many years since anyone had seen me naked. At fifty-one I wanted to get that hurdle over with as quickly as possible.”) Once in the tub, not only did they fit, but Charles began to sing, “You’d be so easy to love”—which is all the reader needs of the scène obligatoire.

On their next date, Skipper took the bus into Manhattan and, after spending the afternoon ripping out black pines from a poison ivy-infested bluff, dined on Dover sole next to Kitty Carlisle at the Hotel Carlyle, where Charles was the maître d’ of its restaurant. This is a tale of eastern Long Island and East 79th Street and the two-hour bus ride that connects the two. Charles’ horticultural horizon had been limited to two tree pits in front of his apartment building in which he planted, every summer, neon-colored coleus and spotted caladiums. When someone stole them—and the replacements—he tried climbing hydrangeas; but a woman in his building tore those down while screaming that they were suffocating the trees. Gardening in Manhattan is not for the faint-hearted.

When small, Skipper imagines a garden into which a prince might appear. When this happens, the first thing Charles does is cut back a crape myrtle, while Skipper watches in horror. Skipper, it turns out, hates to prune, drive, go to doctors, and fly in planes. The prince does all those things. On Long Island all they have to worry about are deer (mesh coverings solve that) and some mysterious creature that massacres a Red Abyssinian banana tree for reasons they never understand; and the fact that eventually gardens grow up and turn sunlight into shade. But that’s all right, since by the time their trees are grown, they also form a privacy fence that hides them from the swimming pools the people on either side have put in—though the garden becomes so well known that neighbors drop in a bit too much for Charles. “So it will be a party of two?” the narrator overhears him asking someone on the phone in his best Carlyle Restaurant manner.

It’s shocking to learn late in the book that the arena of so much horticultural drama that we’ve been reading about is only a third of an acre. It seems far more eventful and populous than that, especially when Skipper’s listing the roses, whose names (Madame Alfred Carrière, Chapeau du Napoleon, Twice-Blooming Rose of Paestum, Souvenir de la Malmaison, Red Grootesndors) he clearly loves to recite. At first, the garden seems to be all roses, like something in one of the old MGM films that Skipper remembers watching as a child—but then, toward the end, we get another glimpse that is, well, more Edward Gorey, if not Suddenly Last Summer. “Will the next gardener cherish the plants I have loved and nourished?” he wonders:

Will he or she feel reverence for the seaweed path alongside the banana grove, mulched with eelgrass I lugged from the beach in plastic trash bags, trip after trip, year after year? There is no reason to believe the banana trees will mean anything special to a new gardener, and eelgrass has almost died out along our shores, so the path cannot be rejuvenated as it decomposes. Will anyone else care about the passionflower vines or the little palm tree I grew from seed? What about Charles’s cucumber magnolia, standing guard at the entrance to our garden?

So how gay is this garden? Well, the Red Abyssinian banana, Ensete maurelii, they name Amonasro, after Aida’s father, king of the Ethiopians in the Verdi opera. Then there’s the description of mimosa “Summer Chocolate” (Albizzia julibrissin) as being “a color I had never before seen in nature, a velvety bluish maroon with warmer Chianti highlights.” The two men christen a pair of silver parasol magnolias Frances and Victor after a rich man and his curmudgeonly widow, who lives at the Carlyle while being courted by Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum for a donation; and the two trees grow like something in The Little Shop of Horrors. What begins as a sunny expanse ends up as a very shady place. As Skipper says, trees are the backbone of the garden, and their taste in trees is a bit noir—strange things with leathery leaves and startling colors—though they love all trees, and (bless his heart) Skipper sees right through people who remove them for their “convenience.”

Yet this man who has no television and likes to hang his laundry outdoors is no garden snob. When Charles comes out the first time, the house is so filled with plants that Skipper has brought in for the winter, he worries that it looks like a crazy person lives there. And when they finally begin to work outdoors together, he explains the chaos to Charles by saying he likes the “laissez-faire look,” which means, basically, that he can’t say no to anything. (“Pruning was something I never had the guts or gumption to do, even though I knew it would be beneficial.”) Skipper loves volunteers (“I don’t like to rip out anything so determined to have its way”). He refuses to use pesticides and herbicides. He even works in a local nursery, though he is not, for all his expertise, afraid to mention a vine “whose name I do not know.” But the man who plants things because they remind him of childhood vacations to Florida and Bermuda is a real horticultural connoisseur, a gardener who not only knows plants’ common and Latin names, but makes sure there will be something going on in the garden in every season—which is what separates pros from amateurs.

He also seems undeterred by limitations of climate. Although the U.S. is divided into gardening zones based on temperature ranges, he writes, “I had my little Florida garden, Zone 7, in drag as Zone 9.” Different readers will recognize his plants, or not, probably depending on where they garden. If you live in Zone 7, almost everything in this memoir is exotic. Here’s a partial list of plants this reader had never heard of: epimedium, echium, mahonia, bindweed, sweetbox, sedum, tensy, Basjoo banana trees, brugmensia, astilbes, creeping comfrey, weeping Alaska cedar, albino Euphorbia, trochodendron, evergreen Florida star anise, European spindle trees, deodar cedar, belles of Ireland, Aubrietia, dracaena, heruchera “Autumn Bride,” Rohdea japonica, and butcher’s broom, not to mention all the varieties of roses and magnolia. Other unknowns: knot gardens, panicle, pangolin, double sport, damping off (“that scourge of seedlings”), and Robiga, the ancient Roman goddess of mold, in whose honor Skipper’s sister gives a party soon after he buys his house in dampish Orient.

The plants, however, are not the subject. “Every garden tells a story,” Skipper says at the start. “Ours tells a love story.” And that is just what the book does. The chapters (with titles like “A Stolen Coleus” and “Mr. Soito’s Peonies”) are framed by two prose snapshots of Charles: in the first he’s clipping a privet hedge, in the second he’s sitting on a porch. Each one conveys the essence of this book, which is not simply a gardener’s memoir but a portrait of a marriage—and an example of mindfulness. That Charles is in the garden seems to be a source of wonder to Skipper. One day Charles, on a ladder, asks Skipper to hand him a saw. “As I handed it up to him,” Skipper writes, “seeing him against the brilliant sky, the word godsend popped unexpectedly into my mind.” Indeed, there is something marvelous in the way this man takes to the garden—”our garden” as Skipper happily notes. The degree of both men’s love for plants is obvious even in the way Charles gives friends a tour while Skipper overhears:

“It’s related to the common summersweet clethra, but it’s so different,” he went on. “It has four seasons of interest. In spring when it first leafs out, it looks as if there is a chartreuse tulip at the end of each branch, like a whole tree full of chartreuse tulips. Then, in early summer, it sends out sprays of flower buds that turn into little white bells dangling along the stalks. They look like lily-of-the-valley flowers. They bloom slowly, through midsummer, and then begin to turn into seedpods, little green balls hanging all along the stalks. Those stay on the tree through the fall, when the leaves turn vivid orange and purple. And then in winter, see, look,” and here he took the group around to the path from where the trunk could easily be seen, “the bark exfoliates, so you have this fantastic gray and tan trunk with long strips of bark hanging off as if it had been shredded. It’s a fabulous tree. You should have one!”

“Four seasons of interest” raises that crucial subject whose capacity to depress the human spirit gardening assuages almost better than anything else: time. “As November turns into December,” Skipper writes, “visitors to the garden often ask, ‘Aren’t you sad that everything is dying?’ ‘Not dying,’ I correct adamantly, ‘going dormant.’” But things do die, of course, and when illness strikes, time becomes even more precious. Yet there is no whining, no complaining, no beating of the breast in this memoir. The tone is good-humored, sweet, and grateful throughout—grateful that Charles is pruning the hedge, or sitting on the porch, or going through an art catalogue with their dog at his feet, while the narrator pursues his great pleasure: reading seed catalogues.

The first part of this love story, when Skipper is describing his childhood, his obsession with opera and movies and peonies, his loneliness as a gay man in Manhattan who starts a group called MGM (Monogamous Gay Men), is, ironically, the funnier part. After Charles arrives, an almost anti-climactic happiness ensues. They prune, plant, visit nurseries, acquire trees, host parties, buy a Havanese puppy, travel, exhibit Charles’ collection of abstract expressionist prints and Skipper’s watercolors at a local museum, move a tree because a neighbor is putting in a fence for a pool. And yes, they get married; and one day Skipper wonders where they will have their ashes scattered. (“Maybe I’d want my ashes scattered in the Sound,” he thinks. “But where might the currents carry them? To Connecticut? I didn’t want to spend eternity in New London.”)

This memoir is, in a way, the antidote to the much more written-about “fast lane” in which gay men seem to be confined to the urban meat market. It really is a kind of fairy tale. To conclude at 38 that one will always be alone, and then to meet someone at fifty and finally have the life of one’s childhood dreams, is a wonderful story. It would be easy to call it charming and lovely, which it is, but it is also very moving. Life and gardening are wonderfully entwined in this story, like the “non-climbing” roses that nevertheless manage to get high into the trees and cascade down in beautiful profusion. That we never see a photograph of the place—and instead have twelve watercolors by the author—is in keeping with the sensibility that permeates the book, which lingers in the mind long after it’s finished.

Andrew Holleran’s latest book is Chronicles of a Plague, Revisited: AIDS and Its Aftermath.