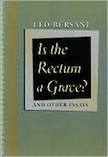

Is the Rectum a Grave?: and Other Essays

Is the Rectum a Grave?: and Other Essays

by Leo Bersani

Univ. of Chicago Press. 211 pages, $25.

LEO BERSANI begins this collection of essays with a concise list of his three major interests: sexuality, psychoanalysis, and æsthetics. To readers not familiar with Bersani’s work, this list suggests that the book will be more traditionally academic—and dull—than it turns out to be. A better sense of what Bersani is about is found in the second of two interviews that conclude the collection. Here Bersani speaks movingly about teaching, writing, and living a “life of thinking.” Bersani began his career at Berkeley as a “respectable” specialist in modern French literature, but over time he allowed what he calls “a kind of interconnectedness” between things happening in his life—psychoanalysis, being a gay man—and his professional work to blur expected boundaries. For Bersani, art is the discovery of endless correspondences in the world. A similar activity informs his writing.

We should not be surprised, then, to find in these essays, originally published between 1987 and 2006, discussions of AIDS, pornography, S&M, camp, and cruising embedded in discussions of Freud, Foucault, Proust, the paintings of Caravaggio, and the films of Almodóvar and Godard. Bersani often references his own books and collaborators, not to call attention to past achievements, but to illustrate the flow of his thinking over time. Everything connects, but there is no final arrival at something called “truth,” because new relationships are always opening up. Bersani, or some created version of him, is present in these essays as a man engaged in a life of thinking about certain recurring and expanding topics. He does not offer fixed interpretations of difficult psychoanalytic and literary texts; rather, he prompts the reader to enter into what Foucault, a major influence on Bersani, calls new relational modes.

Bersani believes that gay men have the potential to discover new ways of being in the world. He also accuses them of failing to do so. “Is the Rectum a Grave?” appeared in 1987, when the homophobia caused by AIDS panic had reached its height. The Normal Heart was playing on Broadway and hemophiliac children were being attacked. Like Larry Kramer’s play, this essay evoked the outrages of that time, but its lasting significance is also due to Bersani’s refusal to accept what he terms “our culture’s lies about sexuality.” These lies involve equating sex with a power struggle between men and women and the resulting oppression of women, and hatred of passive male sexuality, the latter made more virulent by AIDS. Yes, Bersani writes, AIDS has literally made the rectum a grave for many gay men. But the rectum, seen frankly as a component of a gay sexuality that should be celebrated and not vilified, can also be a grave where a flawed masculine ideal of sex as power of one self over another is buried through the shattering of the self, which, for Bersani, is the redeeming value of sex. What is brilliant here is the blending of sex, psychology, and politics into a startling moment of connection.

The title essay is a touchstone in Bersani’s career: the concept of sex as an act of self shattering appears again and again in his work. Like many writers working in queer studies, Bersani finds sadomasochism a useful reference point. The gay S&M relationship both mimics and undermines the dominant culture’s idolatry of power. There is a productive masochism whereby an infant survives the imbalance of power between the external world and the developing ego and whereby an adult experiences the pleasure found in the giving up of ego boundaries in sex and in the appreciation of art. Bersani structures whole essays around gay sexual practices (e.g., “Sociability and Cruising”). In “Is There a Gay Art?” he argues against the pastoral myth of sexuality as “loving and nurturing” and “continuous with harmonious community,” a myth to which gays are no more immune than is the dominant culture. In “Against Monogamy,” he questions monogamy as a futile search for a stable sexual identity and finds in promiscuity the value of curiosity, a genuine interest in other people. In “Gay Betrayals,” he uses this wonderful sentence to deride the goals of the gay community: “It seems at times as if we can no longer imagine anything more politically stimulating than to struggle for acceptance as good soldiers, good priests, and good parents.”

Not all the essays in Is the Rectum a Grave? are devoted to queer theory. “Can Sex Make Us Happy?” is an enlightening reading of Civilization and Its Discontents, an Ur text for Bersani, which makes Freud seem at once human and permanently relevant. In two essays Bersani connects psychoanalysis and art by discussing at length La Grande Beune, a 1966 novel by Pierre Michon, and Jean-Luc Godard’s 1992 film masterpiece, Passion. In these works, both artists create culminating images of pure whiteness that we come to understand, with Bersani’s help, as depictions of our oneness with the world. Psychoanalysis helps us deal with the menace of the world; art enables us to see how “the world cares for us.”

For readers familiar with Bersani’s many books, this collection brings together twenty years worth of his essays that chart the course of a career he humbly calls “a work in progress.” For those coming to Bersani for the first time, this is a perfect place to start. His writing is “difficult” in the best sense of the word: one must read with concentrated attention. But with their repetitions and restatements of core ideas, the essays taken as a whole make the reader believe in the possibility of the new relationality to which Bersani has so passionately devoted his life’s work.

Daniel Burr is an assistant dean at the Univ. of Cincinnati College of Medicine, where he also teaches courses on literature and medicine.