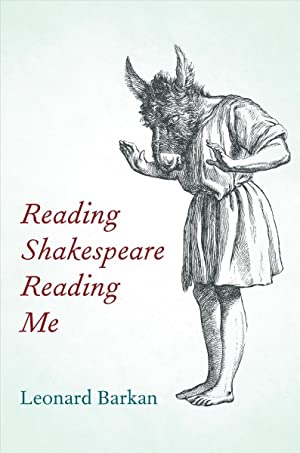

SOME of the most memorable advice in all of English literature comes in Hamlet, when Polonius tells his son Laertes: “This above all: to thine own self be true.” But anyone hearing that advice knows—and Shakespeare’s playgoers probably knew—that it takes time to figure out who you truly are, if ever you do. As Leonard Barkan reveals in his lyrical, literary autobiography, figuring out how to be true to himself happened by performing, reading, and teaching Shakespeare’s work.

In the first few pages, Barkan tells us that this book is about his “lifelong love affair” with Shakespeare. But another way to think about this book is that it conveys how Shakespeare taught Barkan how to love. King Lear and Macbeth, for example, helped him to understand his father’s displays of indignant anger and his mother’s exuberant teaching of Yiddish as performances intended to make an impression on him as a child. His own early experience of acting in the role of Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream helped him make sense of his own “loveless” twenties, when he was both an isolated gay man and a cast member moved by the lovers’ happy endings in the story. The Winter’s Tale helps him discover how he could form such an intimate friendship with a straight male friend, and how that prepared him for true love. The love triangles in the Sonnets bring him to fathom why he fell in love with both members of a couple in one of his first adult crushes. And, in the present, Barkan and his partner’s love of RuPaul’s Drag Race is explored through themes it shares with Richard II. Both dramas reveal how the “real” and the “royal” are based in performance.

Reading Shakespeare Reading Me offers a meditation on not only what’s queer in Shakespeare but also how queer people translate a wide range of what they find in books into their own lives. Barkan remarks: “The world literature of love and desire, with some notable exceptions, is heavily heterosexual, Shakespeare included.” Nevertheless, he finds many places in the plays and poems where queer people can see themselves—boy actors playing women, cross-dressing heroines, profound love shared between same-sex friends—but he also finds a wide range of places that might not look explicitly queer but ended up being deeply resonant for him. In this way, many surprising examples from Shakespeare’s work (some of which may be familiar to readers, others not) hold a mirror up to Barkan in which he can make sense of his identity—as Jewish and gay—at different stages of life. The fact that we can see the plays performed live adds another dimension to how we might find ourselves reflected in a character. Intriguingly, the author locates the “gayest moment in Shakespeare” in The Merchant of Venice. The very opening line has the merchant Antonio announce to his friends, “In sooth I know not why I am so sad.” Antonio’s friend asks what makes him so mournful: his business affairs? No, Antonio says. Then another friend suggests: “Why, then you are in love.” Antonio denies this, too, but this conversation is interrupted by his beloved friend Bassanio. The younger man arrives and, in intimate conversation, says: “To you, Antonio, / I owe the most, in money and in love.” For Barkan, this interaction provides an opportunity to discuss not only the many instances of professed love between people of the same gender in Shakespeare, but also Barkan’s own silence about his feelings when closeted. We learn that it took an older, much more openly gay friend to model for Barkan how to be honest about his own gayness and how to break his public silence about love, a silence that both Barkan and Antonio maintained. Here, as in the rest of the book, the memoir moves seamlessly between the discussion of literary characters and of personal identity. In turn, it reminds us that we learn about ourselves both by encountering characters who mirror us and by confronting those we might be different from in crucial ways. Barkan’s book joins the growing genre of “bibliomemoir,” where authors explore their own lives through the lens of books they have loved. Such memoirs can be a real delight when they reveal the ways in which we figure out who we are by reading about the experiences of others, or learn about ourselves from writers who speak to us. Part of this is realizing that not all writers speak to all people, which is one of the things that makes great literature great: not its universality but its particularity. Among other examples from the bibliomemoir genre, Rebecca Mead finds the distinct stages of her own life thrown into relief by rereading George Eliot in My Life in Middlemarch, while Katharine Smyth is able to process deeply personal grief in All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf. And perhaps Shakespeare especially has something to tell us about how we fashion ourselves through encounters with literature. After all, he is the writer who famously remarks “All the world’s a stage” in As You Like It, and, in Macbeth, “Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,/ That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,/ And then is heard no more.” Like the books that have inspired this new generation of memoirists, not every bibliomemoir will be a perfect fit for every reader. Those looking for more overt discussions of sex might lean toward Mark Doty’s What Is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life, which takes off from the Whitman’s admiration of brotherly love to discuss what he finds erotic. Or those looking for more “memoir” and less “biblio” might try Daniel Mendelsohn’s An Odyssey: A Father, a Son, and an Epic, where the author describes his relationship with his aging father in light of the ancient poem. But those looking for a gay man’s account of coming of age (and aging) while pondering some of the most resonant moments in Shakespeare—as presented by a leading Renaissance scholar—will find much to love in Reading Shakespeare Reading Me.

John S. Garrison is professor of English at Grinnell College in Grinnell, Iowa.