UNSUITABLE

UNSUITABLE

A History of Lesbian Fashion

by Eleanor Medhurst

Hurst. 344 pages, $35.

UNSUITABLE is a lavishly illustrated coffeetable book that makes up in æsthetic appeal for what it lacks in academic rigor. It covers a range of eras and cultures in which women-loving-women have adopted distinctive styles of dress, jumping from profiles of famous lesbians in history (Sappho, Queen Christina of Sweden, Anne Lister of England) to discussions of cosmopolitan cities, forms of entertainment, and political activism. Nevertheless, the book is well-researched, and this eclectic approach is undoubtedly part of its charm.

Author Eleanor Medhurst justifies an interest in the historical importance of clothing in her introduction: “Fashion is what [people’s] clothes become when they are situated within a culture—when they mean something, whether trendiness or the lack of it, age, heritage, class, status, gender or sexuality. … For lesbians, whose very existence subverts the categories of gender and sexuality, fashion can be a conscious statement, a deliberate veil or an everyday expression of a reality that is not the social norm.”

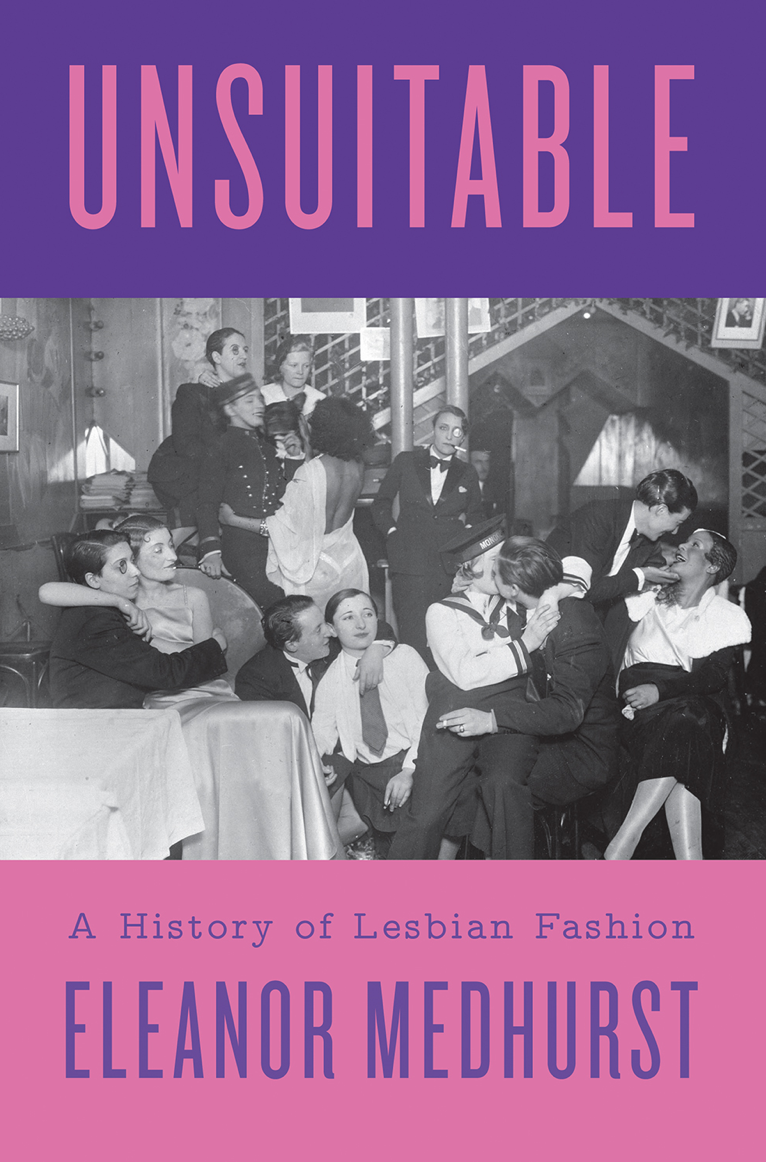

The photographs of women wearing monocles, riding habits, tuxedos with top hats, or ensembles that look like sailors’ uniforms show that lesbian stylishness is not limited to “femmes,” and that lesbians or “lesbian-adjacent” women (who prefer the company of women) have always been style leaders, and not only in counter-cultural communities. In a section titled “The Lesbian 1920s,” Medhurst describes the considerable influence of a lesbian couple, Dorothy Todd and Madge Garland, not only on British fashion but on the arts in general during their reign as chief editor and fashion editor of the British version of Vogue magazine from 1922 to 1926.

The significance of lesbianism, broadly speaking, as an aspect of the “modernism” of the 1920s is deftly explained. It is not a coincidence that women gained political agency when they were allowed to vote in the U.K. in 1918, and in the U.S. and Canada in 1920. As women who have often gone without male economic support or protection, lesbians have traditionally needed—and benefited from—a degree of power and independence not available to women in traditional heterosexual relationships.

Medhurst does not dwell on legal restrictions pertaining to men’s and women’s clothing, but does explain why even the most masculine women of the past often improvised a combination of masculine and feminine clothing for everyday wear. As stage performers, 19th-century women could legally dress as “male impersonators” and earn rave reviews in the press. Photos of the American vaudevillian Ella Wesner in the 1870s, the British music hall performer Vesta Tilley in the 1890s, and the iconic African-American singer Gladys Bentley in a white top hat and tails (circa 1940) are included. The popularity of such performers clearly shows a general interest in “cross-dressing” in times when trousers on women were not accepted in most public venues. At the end of the Victorian Age, Vesta Tilley was the highest-paid female performer on the British stage.

In a chapter titled “We Were Always Here,” the author discusses a literary magazine, Seitó (“bluestocking”), that was launched in Tokyo in 1911 by and for women. It promoted equal rights for all people regardless of gender and faced considerable opposition from the mainstream press and the Japanese government. The most visible women associated with the magazine deliberately combined garments considered masculine in urban Japanese culture with those considered feminine.

Medhurst’s discussion of lesbian fashion carries into the present day, and it includes the long-term influence of the “anti-fashion” look of lesbian-feminists in the 1970s, as well as the rise of T-shirts with slogans as the clearest way to “out” oneself. A T-shirt that reads simply “Dyke” is featured in the last batch of photographs.

This book, the author’s first, seems to be a spinoff of her blog, Dressing Dykes. She has contributed to two displays in Brighton Museum: Queer Looks and Queer the Pier. Unsuitable is likely to surprise and enlighten even readers with an extensive knowledge of the history of women-loving women. It would make a great basis for a documentary film.