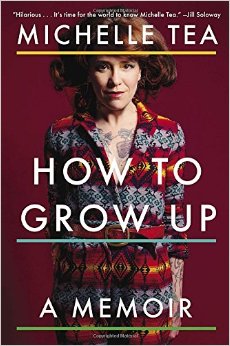

How to Grow Up: A Memoir

How to Grow Up: A Memoir

by Michelle Tea

Plume. 304 pages, $16.

Iconic writer Michelle Tea has written a new memoir, How to Grow Up, an entertaining and logical progression from her earlier biographical works, which chronicled her Goth adolescence in blue-collar New England, her stint as a twenty-something queer prostitute, and her odyssey through San Francisco’s lesbian demimonde. Her latest book is a perceptive, wry snapshot of what a midlife crisis looks like for the alternative set. Part traditional memoir, part self-help manual, the book opens with Tea in her late thirties, newly sober and recovering from an eight-year relationship with a poetry slam champ who’s also an addict and ten years her junior. When she moves into a grungy San Francisco apartment with a bunch of twenty-somethings and discovers a swarm of dead flies and maggots in the refrigerator on Thanksgiving, she realizes that the low-rent bohemian lifestyle she’d grown accustomed to has lost its charm. With her customary dry humor she muses that, “I was by now thirty-nine years old, living with people under the age of twenty-five and a refrigerator full of maggots. If I turned forty while still living there, I was going to have really low self-esteem.” As the title suggests, the book is full of sage advice on becoming an adult, advice Tea manages to dispense without sacrificing her bohemian credibility. Her ruminations on sober sex, her love of designer clothes, and her piece on how she became a successful writer without going to college are not to be missed.

Jim Farley

Voices from the Rainbow

Voices from the Rainbow

Edited by Traci Leigh Taylor

Mother Warrior Press. 351 pages, $16.99

Although some pundits posit that we—at least those of us in North America and Western Europe—are living in a post-gay world, many of the fifty contributors to Voices from the Rainbow would disagree. Editor Traci Leigh Taylor, who’s the mother of actor–choreographer Daniel Robinson, initially asked Daniel to solicit coming out stories via his social media sites. This accounts for many of the “how theater saved my life” entries. Taylor later branched out to interview attendees at the Sexuality and Gender Minority Resource Center in Portland, Oregon; TransYouth Family Allies, headquartered in Michigan; and the Ali Forney Center for young homeless LGBTs in New York. The result is a fairly good sample of ages, races, genders, and geographic locations. Taylor’s tactic was to ask contributors, most of whom use pseudonyms, to include a coming out letter that they might want to write to their parents. There’s a retired Floridian, rejected by his family, who felt obliged to return home to care for his ailing father; a twenty-something British Muslim unable to come out to his parents; a young trans teen in Oregon with family members at various levels of acceptance; an older gay teen from Alabama, rejected by his entire family, who finds social support in New York only to end up back in Alabama due to financial reversals. Adding to the years necessary to compile this book, Taylor asked many contributors to follow up with her after their original contributions to disclose how they were faring. This method yields some interesting details but also contributes to the book’s rather confusing organization and occasional repetitiveness.

Martha E. Stone

The Cambridge History of Gay and Lesbian Literature

The Cambridge History of Gay and Lesbian Literature

Edited by E. L. McCallum and Mikko Tuhkanen

Cambridge Univ. Press. 747 pages, $190.

It’s important to describe this volume as an attempt at a history of gay and lesbian literature, since the project cannot hope to be the final word, a fact that the editors readily acknowledge in their introduction. Each of the 39 essays that make up this volume focuses on a particular time, place, and genre—“Male-Male Love in Classical Arabic Poetry,” “Bildung and Sexuality in the Age of Goethe,” “Native American Literatures,” for example—so some eras and nationalities are bound to slip through the cracks. The essays are arranged chronologically, from the ancient and classical traditions (encompassing not only Sappho, Plato, and ancient Greek and Latin sources, but also those from Arabic and Chinese), through to the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the 19th century, the Modernist era, and on to contemporary times. While the editors take a “planetary” approach, endeavoring to survey as much of the subject as possible, they embrace pluralism over generalization, and their stated hope is to open up categories rather than to circumscribe them.

Jim Nawrocki