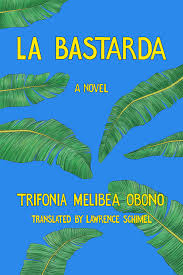

La Bastarda

La Bastarda

by Trifonia Melibea Obono. Translated by Lawrence Schimel

Feminist Press. 112 pages, $15.95

Not only is this the first novel by an Equatorial Guinean woman to be translated into English; it is also the first lesbian one. Equatorial Guinea is the only African country where Spanish is the official language, a holdover from colonial days. Set early in the 21st century in a village where ancestors are venerated, far from any cities, this is the story of a teenager, Okomo (la bastarda), who chafes at her grandmother’s advice to be beautiful and never ask any questions. Marriage (heterosexual) and children were to be the only goals of any woman’s life. Okomo is close to her resolutely unmarried uncle Marcelo, who’s reviled as a “man-woman” by members of their tribe, the Fang, and she refuses all the matches that have been planned for her. Eventually she meets the young women of the “Indecency Club” and falls in love with Dina. Though each is punished after their lesbian activities are revealed, Marcelo finds a way to get them all back together again, and they manage to create a life for themselves in a much-beloved forest. Author Trifonia Obono, a university professor in Equatorial Guinea, has included echoes of European fairy tales in La Bastarda, and historian Abosede George has written a helpful afterword, putting the novel in geographic and historical context. Gay writer Lawrence Schimel’s translation will do much to bring this novel’s attention to the LGBT world.

Martha E. Stone

It seems normal when someone young dies suddenly to ask “What happened?” This book, by the author of When God Was a Rabbit and A Year of Marvellous Ways, tells you what happened; but first, the tone is set by a young widower, Ellis Judd, who has yet to get a handle on his overwhelming grief. His home is filled with mementos belonging to his late wife. Wrapped in her belongings are memories of a triad they made, along with Judd’s best friend Michael. Five years after a car accident in which his beloved Annie died, Judd still can’t discuss it with coworkers, who scarcely interact with him. He hears his wife’s voice everywhere, rejects overtures for new friendships, and seems to walk through life in a fog, giving him an ethereal quality. Annie’s voice seems to keep him alive, but barely.

Memories of Michael, whom he met when they were twelve, are also on his mind, and they are as keen as if their adolescence were just yesterday. They were both boys adrift and became instant friends. Sometimes, in fact, they were more than just friends, but this activity was never discussed. Through the years, they traveled together, shared adventures and hang-out spots, and grew up. Many years later, Michael was, in a roundabout way, the reason Judd met Annie, who was instantly enfolded into a three-way friendship that deepened after Judd and Annie were married. Annie loved Michael as one would a kid brother or a partner-in-crime, and she was as baffled and upset as Judd was when Michael disappeared. Then one day, Michael came home as if nothing had happened, and the trio picked up where they had left off—until the accident, when Judd lost his two best friends.

Terri Schlichenmeyer

Sonya Taaffe is a classical scholar and a poet as well as a fiction writer, and her signature style is both poetic and cosmopolitan. The stories in this collection are characterized by sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures, all of which have a metaphorical dimension. Her depictions of her native New England include so much imagery of rain and ocean waves that a reader can almost taste the drops. Here is the opening scene of “Chez Vous Soon”: “The rain was full of leaves, like hands on her hair as she hurried home. Grey as a whale’s back, the last cold light before evening: the clouds as heavy as handsful of slate, pebble-dash and mortar; the pavement under Vetiver’s feet where blown leaves stuck in scraps to her sneakers, brown as old paper, tissue-torn.” The somewhat pretentiously named Vetiver is going to visit her artist-lover in the rundown apartment where he is obsessively trying to capture the essence of Autumn on canvas. The word-pictures in the story parallel his efforts to capture what seems inexpressible, at least to him, and he plunges into self-destructive frustration.

Most of these stories were previously published in various anthologies and journals of speculative fiction, and they are inconsistent in length, theme, and impact. The “sleepless shores” of the title are not clearly identified, although the spirit world is plausibly described in several stories. In the most unnerving, the dead literally walk among the living. Space does not allow me to do justice to all 22 stories in this collection, but they are all worth reading. They defy simple classifications, and many are likely to leave a reader sleepless.

Jean Roberta

Stephen Hough, an acclaimed British writer and composer who was dubbed by The Economist as “one of 20 living polymaths,” has written a page-turning novel about a contemporary British Roman Catholic, Fr. Joe Flynn. Flynn felt he was born to be a priest and indeed seems to fulfill his duties admirably, even when he finds them joyless and tedious. The novel takes the form of a sixty-entry journal that Flynn was encouraged to keep while on a retreat to which he was sent by an understanding superior after his years of weekly rendezvous with rent boys was made public through one unfortunate incident. Flynn’s feverish descriptions of these young men in their dank and dingy bedsuits may bring to mind Renaud Camus’ Tricks: 25 Encounters (1981). Though Hough’s prose can tend to the purple, there are many unique turns of phrase, whether he’s describing physical imperfection—“cringing with awkwardness as if puberty’s pimples had all erupted at once”—or books in the library at his retreat, where some missals had “frayed rainbow ribbons betraying a long-past liturgical sell-by date.” The book itself is a beautiful object, printed on high-quality paper with a small embossed device on the cover discreetly telegraphing its contents. Martha E. Stone