Lot

Lot

by Bryan Washington

Riverhead Books. 225 pages, $25.

This debut collection of interrelated short stories features a young, gay, working-class Latino man growing up in Houston. The interrelated stories depict in powerful detail the harsh world he lives in, from the violence in his own family to the challenge of forming meaningful relationships. The opening story, “Lockwood,” introduces this world’s brutal tone when the narrator’s friendship with Roberto, who lives next door, turns sexual. Roberto’s family is “full Mexican” and without papers, so the narrator’s father views his family as “superior” to theirs. Roberto and the narrator “tug” each other, the first time while Roberto’s “father was sleeping besides us.” The narrator discovers his older brother has joined a gang. Eventually, Roberto’s family disappears suddenly, even taking “the screws off the doorknobs,” which leads to a parable from the father: “If you didn’t stay where you belonged, you got yourself evicted.” In another story, the narrator’s father takes him to see his girlfriend, and he’s surprised to find a woman as brown as him, having expected a white woman to be the only person his father might leave the family for. In a stand-alone story, “Waugh,” Poke, a gay hustler, develops a romantic relationship with a client, while his “mentor” Rod starts breaking his own rules. In the final story, the narrator becomes close with another restaurant employee trying to send his family back home. A bleak outlook with an easy style, Lot shows complex gay men not often mentioned in fiction.

Charles Green

The Animals at Lockwood Manor

The Animals at Lockwood Manor

by Jane Healey

Mantle Books. 352 pages, $26.

Jane Healey was clearly raised on a healthy diet of Gothic fiction. Her debut novel, The Animals at Lockwood Manor, is steeped in that tradition, specifically the legacy of Jane Eyre (for whom Healey is named), which inspired and was in turn deconstructed in Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca and Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea.

Healey’s heroine, Hetty Cartwright, is a spinster-in-the-making. The year is 1939. Tasked with evacuating a London museum’s collection of preserved animals, Hetty arrives at Lockwood Manor. The house’s mysteries, and Hetty’s battles with its owner, Major Lockwood, constitute the dark half of the plot. There are plenty of shadows flitting down hallways and rumors of secret rooms. This Gothic apparatus is cast against the growing affection between Hetty and Lockwood’s daughter Lucy. It’s a gorgeously orchestrated slow burn, sweet but humidly erotic. An especially memorable scene in which they’re trying on outfits for a ball transitions seamlessly from a girlish charade to the confusion of adult sexuality.

Animals is not a subtle or understated novel. At times the level of meta-awareness is on the nose. Hetty remarks that “when I had first heard the name Lockwood Manor I had imagined something out of Brontë,” and there are frequent references to being locked away as a madwoman. Gothic fans may well respond to these allusions with a wry smile or tolerant hiking of the eyebrow; the uninitiated will just enjoy the story. Either way, this is one of the most genuinely fun riffs on that genre in recent years. At the same time, the book offers an affecting, tender, and unabashedly romantic story of lesbian love that’s reminiscent of novelist Sarah Waters.

Neil McRobert

Becoming a Man: The Story of a Transition

Becoming a Man: The Story of a Transition

by P. Carl

Simon & Schuster. 227 pages, $26.

P. Carl, a distinguished theater artist and academic queer theorist, adds much to the current discourse on transgender realities with this incisive memoir of coming into full embodiment of maleness at age fifty. Exquisitely rendered writing details family abuse, regrets, anger, suicide attempts, and psych ward visits as he struggled with his identity. As a child, Carl always identified as male. His four-year-old self raged against Barbie doll gifts, having asked for GI Joes. Although he lived as a lesbian into adulthood, he always saw himself as androgynous and boyish. Only in midlife did he claim his masculine self, seduced by, but conflicted over, the male privilege it promised.

Although he is “queer and trans culturally” the author rejects nonbinary or gender fluid labels, claiming that “my happiness, my pleasure, my desire, my work, and my hobbies are connected to my maleness and my masculinity.” He celebrates his sculpted chest, testosterone-enhanced muscles, and bristly chin, is stressed by his relationship with his lesbian wife of twenty years and by her hysterectomy for uterine cancer. As the book ends, they’re in Berlin, healing their bodies and their relationship, working on becoming “our best selves.”

More than a lucid analysis of transitioning, Becoming a Man is a beguiling treatise of resiliency and actualization. Carl compels us to question masculinity in all of its constructs. His purpose “in telling you my story is to find words and metaphors and images that can make the invisible visible, but more importantly, can make my invisible known to you in its feeling, a feeling that is not reflected in trans or queer and is not visible through the body parts I was born with.”

John R. Killacky

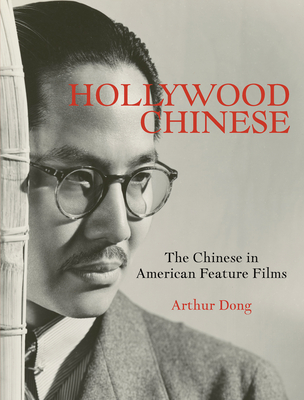

Hollywood Chinese: The Chinese in American Feature Films

Hollywood Chinese: The Chinese in American Feature Films

by Arthur Dong

Angel City Press. 305 pages, $50.

In 2007, Oscar-nominated documentary filmmaker Arthur Dong made a feature about how Asians have been represented on screen by America’s dream factory. The result, Hollywood Chinese, was an illuminating examination of how nonwhite ethnic groups have had their identities distorted or simply ignored for decades. From the “yellow-face” performances of white actors like Peter Sellers and Mickey Rooney to the films of director Ang Lee, Dong managed to cover the evolution from a litany of misrepresentations to more recent and realistic characters.

However, having collected more than 2,000 pieces of movie memorabilia related to Asian cinema, Dong could pack only so much into a ninety-minute film; numerous interviews, posters, and stills were left on the cutting-room floor. The solution was to create Hollywood Chinese, a stunning coffee table book that includes interviews with directors Wayne Wang and Ang Lee and actors Nancy Kwan and James Shigeta. Famous for capturing the nuance behind complex subjects like LGBT soldiers facing discrimination in the military (1994’s Coming Out Under Fire) or homophobic murder (1997’s Licensed to Kill), Dong has assembled a fascinating collection of anecdotes and images in Hollywood Chinese, a book that could fill a gap in a serious film buff’s library.

Matthew Hays