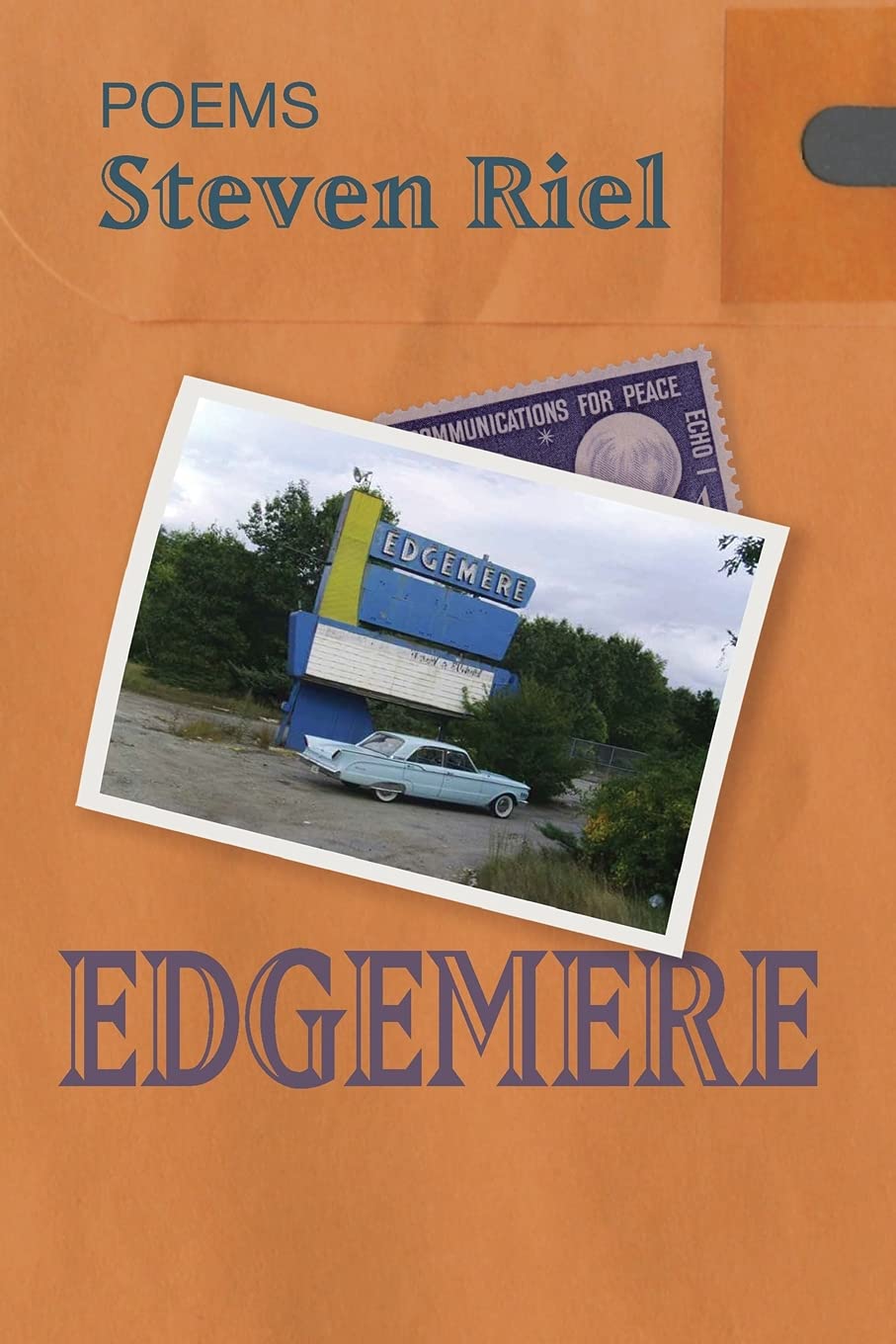

THE ISOLATION ARTIST

THE ISOLATION ARTIST

Scandal, Deception and the Last Days of Robert Indiana

by Bob Keyes

Godine. 242 pages, $21.95

Robert Indiana is best known for a single work: the sculpture of the word “LOVE” in which the “O” tilts to the right. The U.S. Postal Service even turned it into a stamp. But after that, his career was eclipsed by other Pop artists like Andy Warhol and Keith Haring, a neglect that always rankled him. In 1978, tired of the Manhattan art world, he took his resentments to an island off the coast of Maine called Vinalhaven. Although rich enough to hire local boys as his assistants, Indiana was never quite accepted by the local residents, and when, in 1990, he was accused of sexually abusing one of these assistants (oral sex), the community soured on him even more. By the time he died in 2018, his staff was writing checks to themselves on Indiana’s bank account and making art signed by a machine that reproduced his signature.

This is not so much a gay story—though Indiana’s essential loneliness is at the bottom of it—as it is an all-too-familiar portrait of the art world, where careers are managed and strategized with one view above all: making money. The man whose career was based on the word “LOVE” ended up the victim of greed. But part of the problem, at least in this rendition, was Indiana himself. The Isolation Artist is by a Maine reporter who calls his subject an “ass” at one point. What the author refers to as “island justice” is meted out by his own description of Indiana and his inner circle. But if the art world shenanigans grow tedious, this portrait of the Maine folk and their suspicion of outsiders, not to mention the behavior of impoverished young men when a sugar daddy is plopped down in front of them, reads like a film noir.

Andrew Holleran

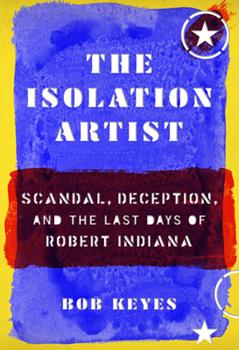

THE AUDACITY OF A KISS

THE AUDACITY OF A KISS

Love, Art, and Liberation

by Leslie Cohen

Rutgers Univ. 265 pages, $24.95

Leslie Cohen was one of the four figures sculpted by George Segal for the Gay Liberation Monument in Greenwich Village, cast in 1980 and put in place, after much contention, a dozen years later. Cohen’s social life was so jam-packed that her participation in this project was just one of many adventures. An early baby boomer and self-described tomboy, she was born into a dysfunctional family and developed a “mutual preservation society” with her mother. Cohen started out at Buffalo State College, and on her first day met Beth Suskin (the other lesbian figure in the Segal work). The two women immediately developed a deep friendship but then lost contact for many years, later finding each other and living through a tumultuous time that culminated in their eventual marriage.

Cohen had planned on a career as a high school history teacher but became interested in art history early on, eventually receiving her master’s degree. Through a series of lucky breaks and a well-connected art professor, she started working in galleries and made important connections in the art world. In the late 1970s, she and three other lesbian friends became the first women in Manhattan to own and manage their own club, one without any apparent Mob interference. Located, as one of her friends said, in “Straightsville” on the Upper East Side, Sahara was intended as a “nightclub with a salon feel,” where Cohen curated art, booked talent, and made sure that everyone was having a good time. This fast-moving memoir touches on many themes, including the proverbial trio of “sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll.”

Martha E. Stone

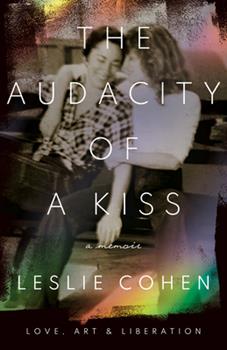

No matter how far any of us get from our childhood torments, or from the first deaths from AIDS, the pain never quits calling us back. Even humor can only partially assuage the sting. But for a poet like Steven Riel, the past can bring to life how memory may be a window to a new life. He bluntly states what his life was like “Since I’m a fifth-grade fag/ who gets throttled in the skunk-cabbage swamp/ where the teacher’s aide can’t see.” By pretending to be “the high-heeled mom … protecting her split-level family” with Glade air freshener, Riel mocks the commercials for a product that “eradicates odors and frees up an hour for girly boys/ to inch into elbow-length rubber gloves.” His poems teeter on the edge of playfulness and dread. He captures the angst of having his brother, dying of AIDS, discharged from the hospital.

Riel’s subjects range from the delight of wearing high heels to retrospectives on his hometown to meditations on the natural world. His spare but musical language and deft shift in syntax can be riveting. He brings back the delight and unease of finding his true desire: “Unnoticed underclassman/ on a locker room bench. I/ don’t let slip a mammoth moan/ when the Varsity MVP strips down (Good God)/ to just plump cockhead, its scrolled corona—/ trophy-winning mousetrap—inches/ from my enormous, untamable eyes.” Riel’s poems ride the emotional rollercoaster of love and loss in a way that feels a lot like what it means to be alive.

Bruce Spang