LOVE, LEDA: A Novel

by Mark Hyatt

Peninsula Press. 173 pages, $11.40

Nicknamed Leda, a young gay Brit shunned by his family recounts his life on the streets of 1960s London. Secure in neither work nor home, he lives by his wits and sometimes the kindness of strangers, often older gay men or straight women, whose beds he fitfully shares. Leda makes his way from one studio to another, occupying vacant buildings and all-night clubs, with a few pence in his pocket, whether stolen, earned, or received as a gift.

Author Mark Hyatt records Leda’s days and nights as a series of queer encounters. Sometimes they’re just a place to spend the night, sometimes there’s sex—neither fulfilling. Asked about his life, Leda replies: “Occasionally I am the victim of sex. Sometimes love. But both are fatal.” Some scenarios on a given day: spotting a man with piercing blue eyes, he chats him up. Traveling to an abandoned cottage, they camp for a night of eating, drinking, sex, and sleep. Left in the Underground afterwards, Leda remembers a friend who lives nearby. Opening the door, Thomas discovers a disheveled Leda, invites him in for a bath, food, a few pounds, and a place to stay for awhile. Ending the week, Leda escorts two young boys to a beach. He notes their every move: trains taken, swim trunks changed into, water explored, treats shared, amusement rides enjoyed. Turning the boys over to their mother afterwards, with whom he will spend the night, Leda sits by the Thames and ponders his life: “I have had twenty years of living and what I see I don’t care for. I think I’ve exhausted my youth and if I look like a prize fool, then the world prizes fools. I am a fool and a romantic.”

Joe Ryan

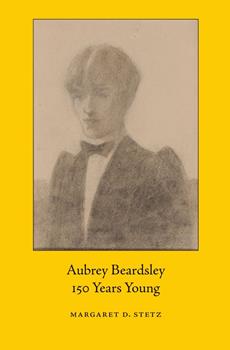

Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) was an extreme æsthete who took a fine arts approach to a primarily commercial body of work. His provocative and playful designs frequently feature phallic symbols (and actual phalluses), combining the spareness of Japanese woodblock prints with the florid ornateness of Art Nouveau. Last fall, Mark Samuels Lasner and Margaret D. Stetz co-curated a superb show celebrating his life and work at New York City’s Grolier Club, a haunt for bibliophiles since 1884. Now Stetz has collected her lively insights from the exhibition’s title cards, along with color plates of Beardsley’s work, letters, and photographs, in a slim volume that packs a big punch.

Stetz’ astute analysis of Beardsley’s output highlights segments of his tragically short life (he died, at 25, from tuberculosis). A mama’s boy with a deadbeat dad, the would-be writer and self-taught artist from Brighton became a successful, easily bored commercial designer who churned out theatrical posters, book covers, and magazine illustrations that often had no connection to the words they accompanied. Beardsley paired the grotesque with the refined in singular and surprising ways, such as drawing a tumescent-looking penis with a scowling face sporting a tiny top hat. He couldn’t resist ridiculing whatever he admired, including himself; he wrote in a letter that he had “a sallow face and sunken eyes, long red hair, a shuffling gait and a stoop.” Yet he was stubbornly childlike and “seemed never to settle upon a sexual orientation, let alone sleep with anyone.” After the 1895 arrest and prosecution of Oscar Wilde (a client and prickly rival with whom Beardsley shared a love of wit and refinement and a hatred for the philistine), all suspected homosexuals were fair game, and Beardsley was “thrown to the lions of British prudery.”

Michael Quinn

Ezra gazes in the mirror: short, coke-bottle glasses, snaggletoothed. Not a great way to present himself. How to impress his peers without having the means to do so? Be smarter; present objects of desire that high schoolers crave: fashionable sneakers and uplifting drugs. White $10 sneaks bring $100 after Ezra adds a designer swoop. Ground up Sudafed and sea salt, marketed as a special high, sells for $50 a tab. Ezra rolls in the cash, until a student almost overdoses. Busted, he departs to reform school: New York’s Last Chance Camp beckons.

One day a newbie arrives, redheaded with a lanky, athletic build. “Call me Orson,” he says, with piercing blue eyes and a pleading smile. Ezra’s heart swells, but he tells himself Orson is not meant to be his toughie, just a friend helping him through the summer. Time spent selling fake drugs leads to a shared life after camp. Small apartments, often with one bed, let Ezra snuggle on Orson’s chest—and more—as they dream of bigger hustles. Their closeness leads to a dynamic duo: Orson, the “lieutenant,” executes schemes that Ezra, “little dude,” brings about through sheer brain power.

Orson relaxes people through warm temple pressure, a process they name Synthesis. Women with money descend; hundreds swoon at his magical touch. Their company, NuLife, develops the Bliss-Mini, a portable machine that promotes “transcranial magnetic stimulation,” leaving hoodwinked customers transfixed. Millions of dollars flow in. Further schemes at NuLife lead to swarms of converted customers. Emily, an actress of limited talent, becomes besotted with Orson; slowly they evolve into the couple Ezra dreams of himself. As their wedding approaches, Ezra muses: “How do you force yourself out of love, if you’ve loved someone for a long time?” Before the couple marries, fate plays its final hand, when Ezra’s and Orson’s futures are irrevocably changed.

Joe Ryan

PINK TRIANGLE LEGACIES: Coming Out in the Shadow of the Holocaust

PINK TRIANGLE LEGACIES: Coming Out in the Shadow of the Holocaust

by W. Jake Newsome

Cornell University Press. 304 pages, $34.95

For those interested in the “problems” of queer history, this book is an excellent introduction to the issues associated with confronting queer historical memory. The first chapters tell how the Nazis, using paragraph 175 of the pre-existing German legal code, placed homosexuals in concentration campus, branding them with a pink triangle. The bulk of the book, however, focuses on how the story of the “Pink Holocaust” slowly came out of the shadows and came be accepted as a “legitimate” part of holocaust memory.

Constructing the history of the Pink Holocaust faced numerous obstacle and challenges. Camp survivors, still considered legal prisoners and not released when the camps were liberated, were reluctant to come forward with their stories. They still faced additional persecution under paragraph 175, which wasn’t fully repealed until 1994. Getting the government authorities and the German public to see them not as violators of a criminal statute but as victims of a fascist ideology was another chapter. There was a debate about the numbers, with early accounts putting them in the millions. The actual total was closer to 100,000. There was also a debate over meaning: just exactly what did the pink triangle symbolize? Initially some argued it only applied to gay men; women were not targeted under paragraph 175. In the 1980s, the pink triangle was adopted as a symbol by AIDS activists. Newsome holds up the pink triangle as a universal symbol of the queer resistance, appearing in 23 memorials in nine countries—without acknowledging that many groups now avoid this symbol because of its association with Nazism. That said, it remains a valid tribute to those who suffered and struggled for LGBT freedom.

Fred Fejes