COACHELLA ELEGY

COACHELLA ELEGY

Christian Gullette

Trio House Press, 80 pages, $18

A feeling of imminent doom pulses through Christian Gullette’s refined poetry debut, Coachella Elegy. In climate-ravaged California, people burn through resources, party like it’s the end of the world, and “everyone’s song of summer/ is about addiction and love” (in “Desert Ride”). The collection is structured in four sections of verse about travel to four destinations, with three prose interludes that reflect on the journey. Stops include a sun-scorched Palm Springs and an ultra-gentrified San Francisco, where an AIDS-haunted Castro funeral home is “now shuttered and slated for condos” (“City Bees”).

At the collection’s heart are the speaker’s relationships with two men, each strained by illness and tragedy: an emotionally disturbed brother who flips his jeep in a fatal highway accident, and a husband who emerges on the other side of a cancer diagnosis with a prosthetic eyeball. Several poems are set in Airbnbs, 21st-century Edens where good-looking men party poolside, palm trees reflected in their mirrored sunglasses, while wind turbines slowly spin in the distance. When a “guy fidgets with the knot/ in my swimsuit,” the speaker observes how “My husband watches from a strip/ of artificial grass” (“Mid-Century Modern”). In “Outdoor Shower,” the speaker, pressing up against his husband’s backside, imagines the way their bodies might appear through the glass brick wall, “unseen but also seen … a nude blur.”

Like modernist sculpture or mid-century furniture, the poems are stripped down to their barest lines. Powerful, deep-seated feelings—fear for his husband’s health, sadness about his brother’s shattered life, anguish over politics and climate change—surface like tremors that crack the stone-faced façade of coolly observed emotions. Taken together, the poems work like a pointillist painting in which each carefully placed dot of color contributes to an unsettling picture of grief, desire, and sorrow for a ruined world.

Michael Quinn

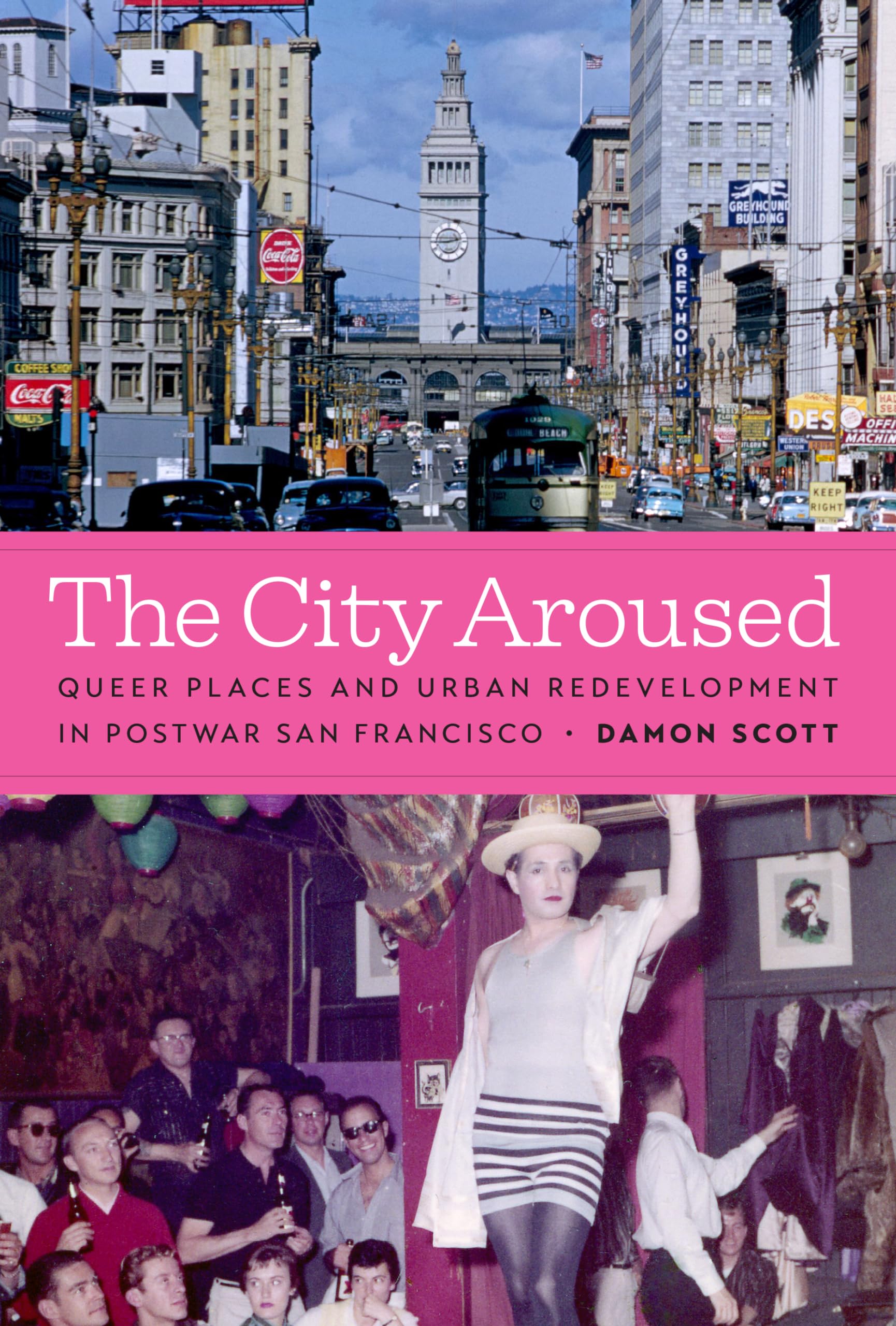

THE CITY AROUSED Queer Places and Urban Redevelopment in Postwar San Francisco

by Damon Scott

University of Texas Press. 336 pages, $45.

A testament to the law of unintended consequences, The City Aroused tells the story of how a crackdown on gay life by the city of San Francisco in the 1950s led to the first stirrings of gay rights activism and eventually to a full-blown movement.

Author Damon Scott puts the postwar city of San Francisco under a microscope, focusing on how government policies and actions impacted the city’s waterfront. Bars and other relatively low-rent establishments in that area during the repressive 1950s became gay hangouts. As white, hetero-normal families moved to the suburbs, city officials grew concerned about who was left—racial and ethnic minorities, to be sure, but also an excessively “single” population. Like officials all across the nation, the city went after the gay population by cracking down on “vice.” At first they did so by trying to contain the gay population within one small, run-down area, and then they literally destroyed its main venues through urban development. In place of bars and hangouts with names like the Ensign Café, the city built freeway ramps and envisioned upscale offices and apartments.

But by cracking down on spaces where queers could gather, the city unintentionally helped foster a political reaction—early stirrings of political consciousness before Stonewall. As Scott argues, changes in the built environment fostered a change in the understanding of sexual difference. The city thus got the opposite of what it tried to accomplish. By destroying gay spaces, it helped create gay collective action. Scott tells this story with meticulous attention to detail but without sacrificing readability.

H N Hirsch

ADAM IN THE GARDEN

ADAM IN THE GARDEN

by AE Hines

Charlotte Lit Press. 85 pages, $18.

AE Hines’ second collection offers the essence of gay life in poems that range from intimate to nearly galactic. Along with poems about domesticity and friendship, he offers some tough-minded images. A poem written in Matthew Shepard’s voice ends: “But for twenty years, for thirty, far longer/ than I was alive, our people remember/ my name. It blooms/ from their lips like a cold prairie rose.” It is the mark of a gifted poet to be able to write about a specific event in a way that remains fresh and strong over time.

Another example of how Hines can turn a single incident into a near anthem is the end of his poem about the drag show that continued despite the local power station being shot up by a nutcase: “know you’ll find no wilting flowers here/ just at the edge of the stage. With its green/ stiffened spine, the boozy and voluptuous/ tulip takes no bows. With outstretched petals/ outlasting gravity and death, it refuses to bend.” There is also much tenderness. One poem ends “Some quiet evenings I go out/ to sit with them, all the men/ I’ve been, and beneath/ that same quilt of stars retrace/ my path, the weak orbit/ of every man to touch me.” This segment by itself reveals many angles of this warm and determined poetic voice.

Alan Contreras

BORN THIS WAY

BORN THIS WAY

Science, Citizenship, and Inequality in the American LGBTQ+ Movement

by Joanna Wuest

Univ. of Chicago. 293 pages, $32.50

LGBT activism has a longstanding relationship with the illiberal notion of being “Born This Way” (as gay, lesbian, etc.)—illiberal, because it argues that the sexualities behind the queer alphabet soup are not a choice but a predetermined reality (biological or otherwise) to which one is awakened at some point and with which one must come to terms, hopefully to embrace and even celebrate.

Joanna Wuest argues that beyond the catchy slogans one can trace an ideology that has subsumed LGBT activism, politics, law, science, and healthcare since the 1950s. Genetic or prenatal determinism has been the major arrow in the activist’s quiver, readily adjusted to counter the arguments of anti-gay conservatives. In Wuest’s critique, sexual determinism became a tenet of faith in the LGBT corridors of power early on, leading to gay normalization that neutralized activists’ erstwhile radical queer agenda. She convincingly shows that every stakeholder in the LGBT movement has channeled some version of “Born This Way.” Even the anti-establishment purists seeking to topple essentialist categories in favor of flexible identities are shown to be entangled with remnants of determinism.

Despite its intriguing premise, the book is consistently undermined by the narrow lens through which the history of the LGBT movement is being viewed, namely the persistence of determinism in LGBT politics, which she suggests is ideologically or ethically compromised. Her history of the science of sexuality fares no better, marred as it is by her lack of sophistication on the workings of science; and one is struck by her denial of the potential of science to tell us anything at all about the biology of sexual orientation and gender identity. And she fails to recognize that the “Born This Way” hypothesis has often been a political expedient rather than a core dogma.

Yoav Sivan

AMERICAN POLY: A History

AMERICAN POLY: A History

by Christopher M. Gleason

Oxford University Press. 248 pages, $34.95

Nonmonogamy and multiple-partner relationships seem to be all the rage. From the recent buzz surrounding Molly Roden Winter’s memoir More: A Memoir of Open Marriage, to the Peacock network’s reality TV series Couple to Throuple, it’s beginning to seem like the religious Right’s fears about the fall of traditional marriage were justified.

Christopher Gleason’s American Poly is a well-researched attempt to show how a once-hidden practice has emerged into the open. While distantly related to the utopians and freethinkers of the 19th century, modern polyamory traces its roots to the U.S. counterculture and “free love” movements of the 1960s. Gleason charts the evolution of polyamory and its efforts to define what the practice is all about. For example, defenders of polyamory in general are adamant about not being confused with “swingers,” insisting that the lifestyle they favor is a way to maintain and strengthen the bonds between committed partners.

While acknowledging attempts by the polyamory community to connect with gay people and bisexuals, much of American Poly focuses on white heterosexuals and their groups, which often consist of one man and two or more women. There is scant mention of same-sex attraction between female partners, while nonwhites are brought into its story only in an afterword about the current state of polyamory. Even Peacock’s “groundbreaking” reality show plays it fairly straight, with only one same-sex couple, a bisexual man and his “don’t-knock-it-’til-you-try-it-sexual” partner.

Reginald Harris

AMBIVALENT AFFINITIES

AMBIVALENT AFFINITIES

A Political History of Blackness & Homosexuality after World War II

by Jennifer Dominique Jones

Univ. of North Carolina. 282 pages, $29.95

In her epilogue, Jones summarizes Ambivalent Affinities as a study of “critical moments in which ideas about homosexuality crossed paths with contests over Black political empowerment.” Such intersections were not necessarily high points for either, she concedes: “The power of the hetero-normative state [was]an influential force that shaped the strategies of mainstream civil rights organizations” toward gays, as when major figures in the SCLC ousted gay Black activist Bayard Rustin. (This sad moment is well depicted in the recent Netflix movie Rustin.) Indeed, for Jones “the very production of homosexuality as a political category [has been]tethered to the non-normativity of Blackness as a way to stigmatize both.”

As that language makes clear, this is a (presumably revised) doctoral dissertation, weighed down by discipline-specific jargon that’s de rigueur in such treatises but makes for slow reading for the rest of us. Several chapters deal with instances in the 1950s and ’60s when white racists associated Civil Rights activists with homosexuality. But then, as Jones herself points out, homophobia was prominent in that era as a result of the McCarthy-led purge of alleged Communists from the federal government. Conservatives associated non-Black liberals with homosexuality then as well.

Worthy of pause is Jones’ repeated assertion that white heterosexual Americans’ views of Blackness and homosexuality have been “imbricated”—one of her favorite words. The Gay Rights Movement did try to establish parallels with the Civil Rights Movement, but, as Jones herself shows, the latter often wanted nothing to do with us and made little use of homosexuality when trying to redefine the way white Americans saw their Black fellow citizens and their rightful place in our society. So it’s not entirely clear how much real “imbrication” was going on.

Richard M. Berrong