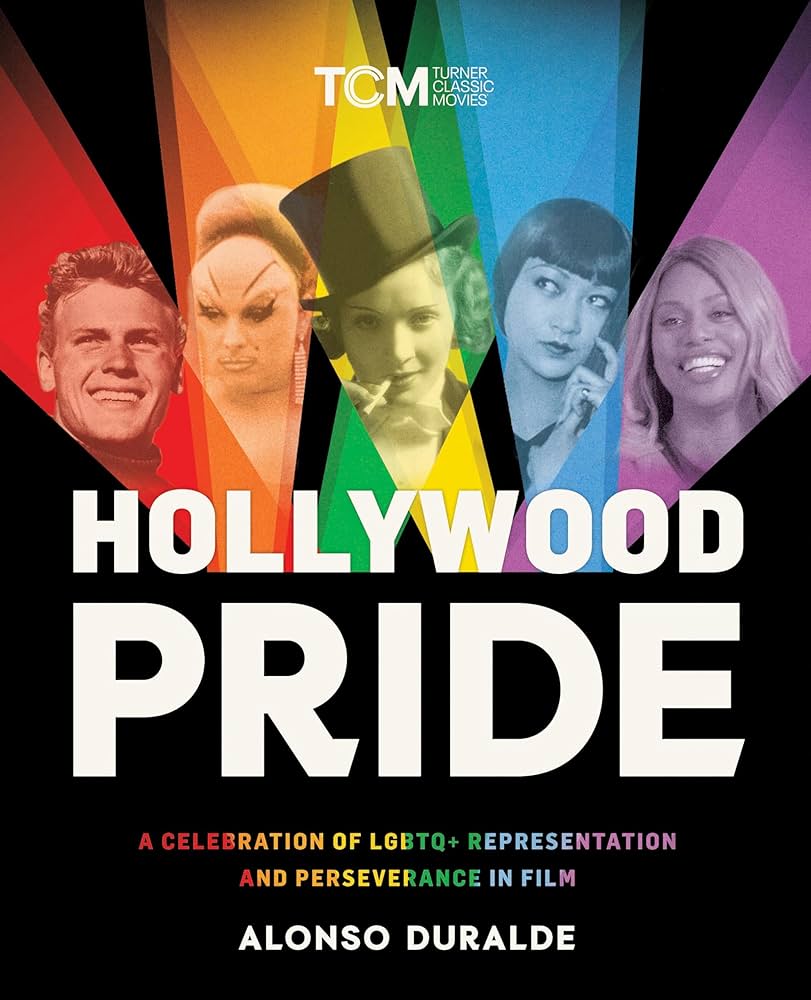

HOLLYWOOD PRIDE

HOLLYWOOD PRIDE

A Celebration of LGBTQ+ Representation and Perseverance in Film

by Alonso Duralde

Running Press. 336 pages, $40.

Brimming with infectious enthusiasm, Alonso Duralde’s Hollywood Pride is an ambitious overview of LGBT representation on the big screen, full of brief but fact-filled entries on the most important movies and the people who created them. The book’s title is a bit of a misnomer, as it includes many films that were decidedly un-Hollywood, either because they were made outside the Hollywood studio system (such as John Waters’ films) or because they were not American movies at all (such as Mädchen in Uniform, made in Germany in 1930).

Serving as both a strong introduction to the newcomer or as a solid reference for the queer film buff, a survey this far-reaching and satisfying hasn’t been created since Ray Murray’s excellent Images in the Dark (which is now almost thirty years old). If there’s one minor quibble, it’s that Duralde occasionally favors celebration of the stars over acknowledgement of the turbulence surrounding some of the figures he covers. For example, Lily Tomlin is justly praised for her remarkable talents and contributions, but there’s no mention of the longstanding criticism that it took her way too long to come out publicly as LGBT. But this is a minor matter. Hollywood Pride makes for lively and illuminating reading, a welcome addition to any film buff’s library, queer or otherwise.

Matthew Hays

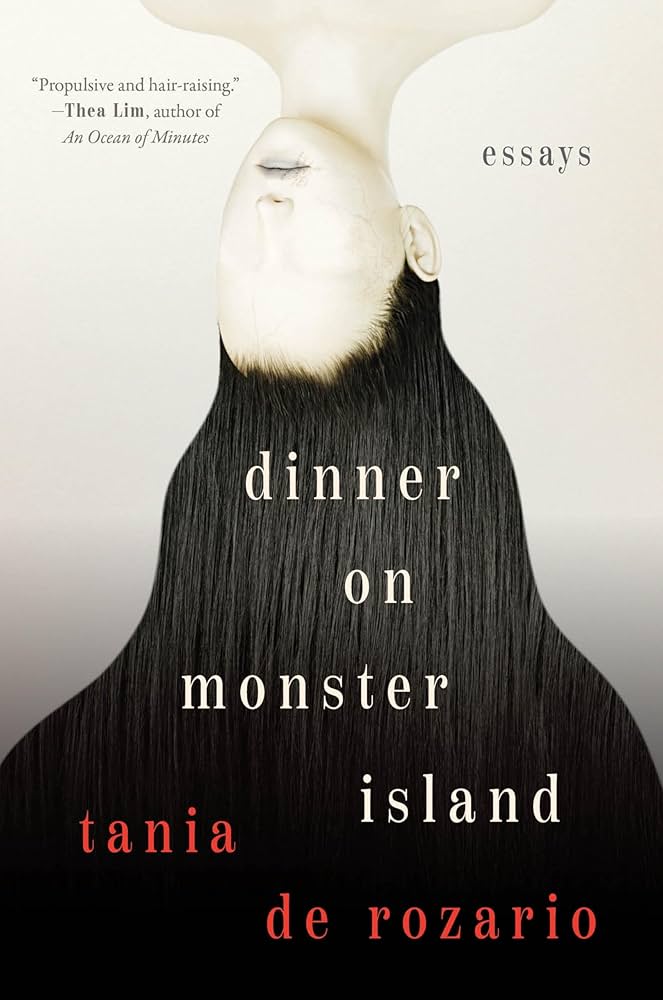

DINNER ON MONSTER ISLAND: Essays

DINNER ON MONSTER ISLAND: Essays

by Tania De Rozario

Harper Perennial. 192 pages. $17.

Within the first few pages of Dinner on Monster Island, a collection of essays on monsters and heroes within and without, Tania De Rozario mentions that it took her years to figure out that she probably loved the horror film genre so much because she lived it. By young adulthood, she had endured her mother’s betrayal, an exorcism (neighbors spent seven hours attempting to pray away the gay), her estranged father’s suicide, and state-sanctioned homophobia and fat phobia. De Rozario, an author and visual artist who grew up in Singapore, takes this trauma and alchemizes it into a Roxane Gay-esque book of essays.

While heartbreaking, the work is also entertaining, especially as De Rozario unpacks several horror films in which women are terrorized: “If horror has taught me anything, it is that nothing has been as enduringly terrifying across time and place as women’s bodies” (as witness The Witch, Carrie, Ringu, and The Exorcist). The collection is awash in clever gems (some could use a little more context), such as De Rozario’s wry take on family dynamics in The Exorcist: “Like mine, her single mother did not know what else to do with her daughter’s deviant behavior.”

Other essays cover Radiohead’s “Fake Plastic Trees,” inhumane treatment of migrant workers, psychological hauntings, Singapore’s draconian laws, Westworld (some of which was shot in Singapore), and finding ways to be hopeful. She writes evocatively of life as a young queer person longing for a “mirror-morsel” of herself. The author was surprised to find it on the radio upon hearing Sophie B. Hawkins’ “Damn, I Wish I Was Your Lover” and again in k. d. lang’s “Constant Craving.” In Dinner on Monster Island, De Rozario gives readers plenty to sink their teeth into, declaring: “Fuck leaving bread crumbs. I want to leave a feast.”

Chaya Schechner

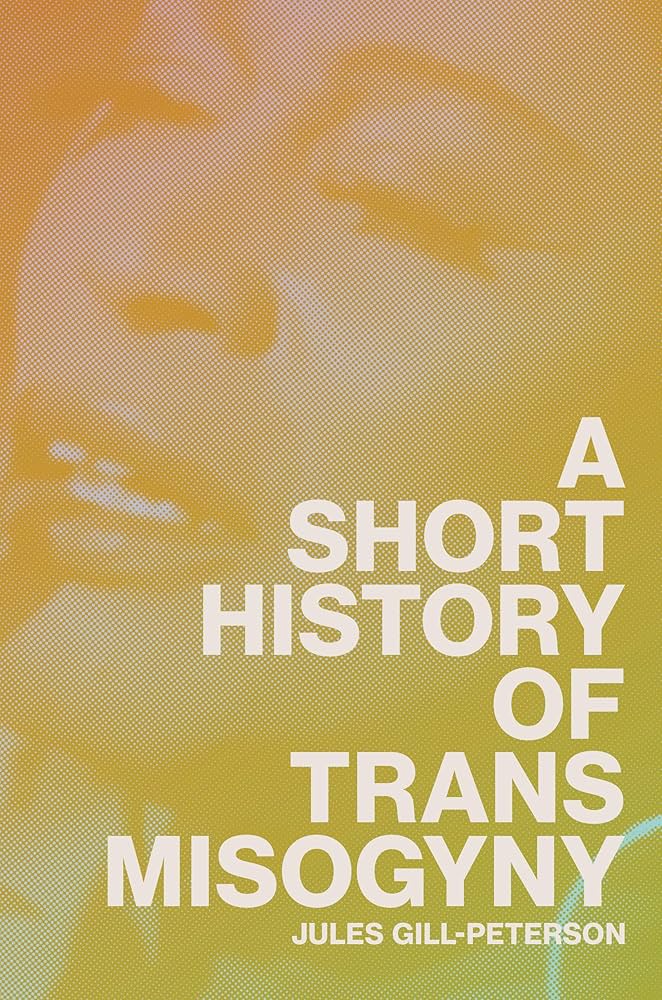

A SHORT HISTORY OF TRANS MISOGYNY

A SHORT HISTORY OF TRANS MISOGYNY

by Jules Gill-Peterson

Verso / New Left Books. 192 pages, $24.95

The term “trans misogyny” was popularized by Julia Serano in her book Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity (2007). In A Short History of Trans Misogyny, Gill-Peterson (who teaches history at Johns Hopkins) focuses on official conceptions of trans femininity as expressions of white-supremacist, colonial cultural intervention. For example, the author of the new book focuses on “trans panic” as a defense used by those accused of anti-trans violence in the U.K., a defense that goes back to the British criminalization of the “hijras” of northern India in 1852. Hijras were born male and trained to perform as singers and dancers, and they dressed as women throughout their lives. Their role was interpreted by the British Raj as “prostitution” and “vice,” which had the self-fulfilling effect of separating them from their traditional work as singers and dancers and forcing them into sex work.

The author describes the parallel treatment of African-American cross-dressers in the antebellum South, and goes on to discuss the “street queens” and masculine hustlers in John Rechy’s groundbreaking 1963 novel City of Night. She concludes with the murder of a sex worker in the Philippines in 2018 by an eighteen-year-old white American serviceman, who used trans panic as a defense in the ensuing trial. Gill-Peterson connects this case to patriarchal military control and violence against people of color who are perceived as gender-deviant. The author wraps up her argument with a passionate defense of trans femmes.

Jean Roberta

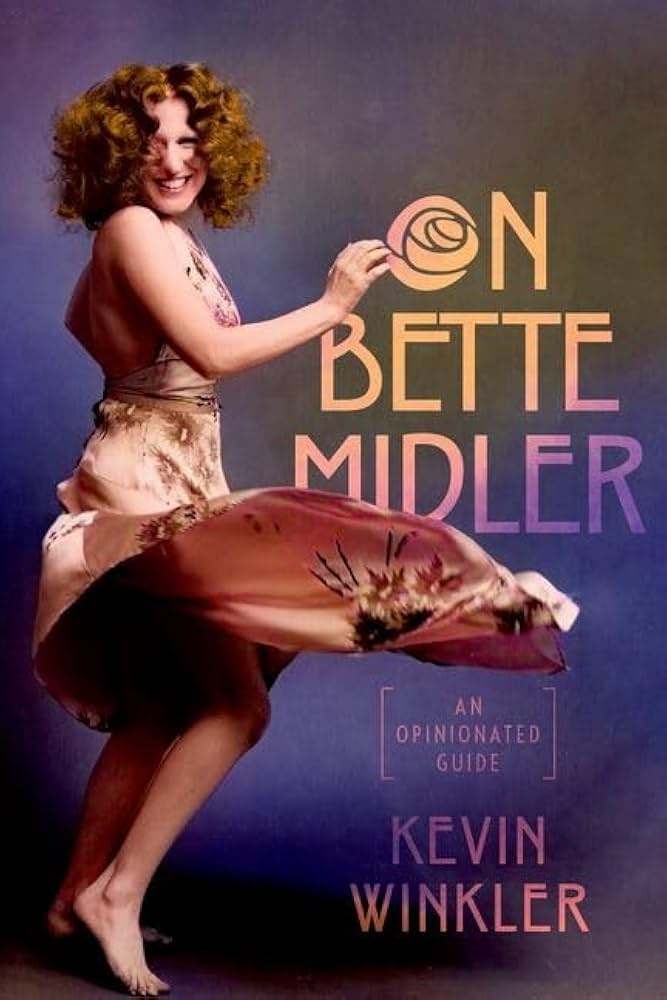

ON BETTE MIDLER

ON BETTE MIDLER

An Opinionated Guide

by Kevin Winkler

Oxford Univ. Press. 224 pages, $29.99

It’s immediately obvious that former archivist Kevin Winkler adores Bette Midler. His “opinionated guide” is unabashedly that—a measured retrospective of how the Hawaiian-born bookish teenager became a legend. He tracks her career from inauspicious beginnings as a film extra through her incandescent rise to superstardom and beyond. The Divine Miss M burst onto the scene as a solo act at the Continental Baths in the basement of the Ansonia Hotel in Manhattan. Gay men in towels applauded her persona as a brash, brassy, and bawdy broad. Her bigger-than-life persona expanded upon the gay camp sensibility by “mocking the deadly serious, reveling in show business references, gleefully slipping in and out of new identities, upending the whole notion of a diva’s relationship with her fans.” A powerhouse rendition of “Friends” became a stirring anthem to the faithful and the fabulous.

Midler proudly carried the banner of vulgarity—and vulnerability—to her fans in a series of outrageous, often salacious, stage concerts, introducing Delores DeLago, a mermaid in a motorized wheelchair. These performances, which featured songs from all eras, wild costumes and sets, and a host of comic characterizations, eventually morphed into The Showgirl Must Go On, which opened in Las Vegas in 2008 with more showgirls, more mermaids, and more rambunctious comedy than ever. Along the way, she recorded over twenty studio and sound track albums, starred in such films as Beaches (1988), Gypsy (1993), and The Stepford Wives (2004), and headlined a Broadway revival of Hello Dolly! in 2010, for which she won a Tony Award. Most people probably knew her best for her TV talkshow appearances, notably on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, who invited her on as his very last guest.

Robert Allen Papinchak

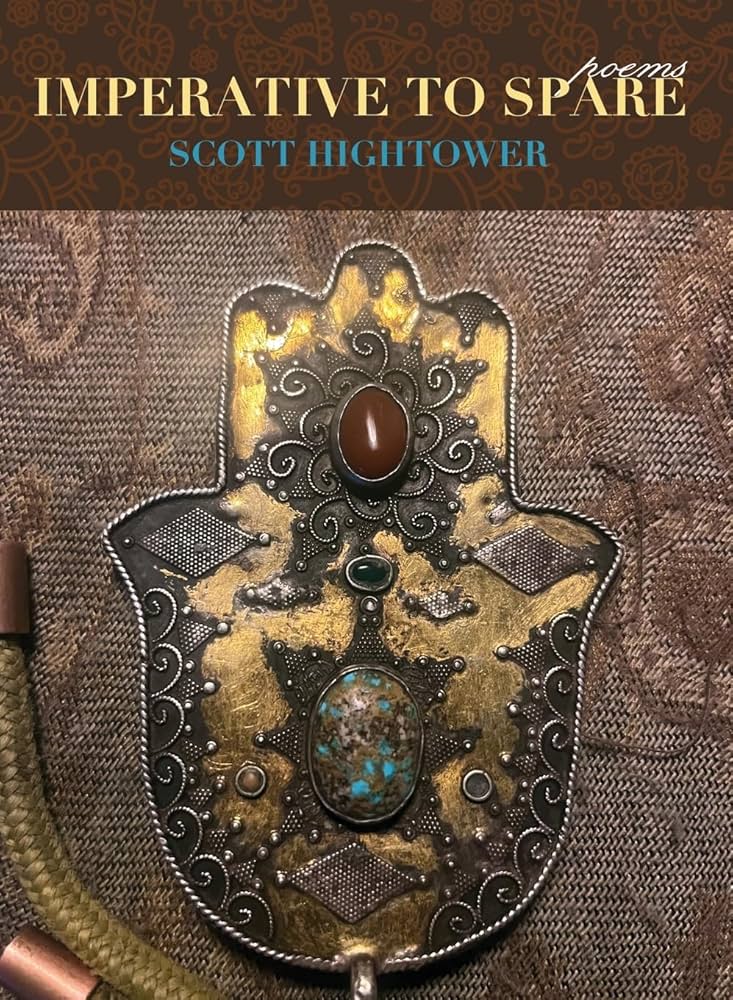

IMPERATIVE TO SPARE

IMPERATIVE TO SPARE

by Scott Hightower

Rebel Satori Press. 176 pages, $16.95

Scott Hightower’s Imperative to Spare opens with “Aubade Horribilis”—making annus horribilis a poem for dawn, setting the stage for the loss of a partner and a speaker who tells it like it is: “Fate has parted us. I still live/ diminished on the shore.” When his partner, a physician, suddenly dies on a city sidewalk, the speaker reminds us that grief is inevitable but endurable, admitting in “It Would Have Been My Preference to Have Gone Before You” that he doesn’t “have a clue/ what to do/ with myself,” but mustering in “Empty Arms” the resolve to renovate their terrace with “roses, coleus/ and sweet potato vines.”

This gumption is also seen in “The World Is Full of Beautiful Things” as it catalogs what the partner avoided: that, although the doctor “would have liked/ growing into an aging/ body,” he will “never have to suffer/ any disabling disease.” In “Continuing,” the speaker reveals that he himself is “trying to figure out/ if I’m still in a meaningful/ conversation.”

With plenty of references to popular culture (Ethel Merman, Harold and Maude, etc.), biblical characters, and ekphrasis, it’s the poet’s voice that comes through. In “Gashapon,” the speaker identifies with a vending machine’s sign that reads “The light inside/ is broken, but I still work,” confessing: “Me, too, vending machine./ Me, too.” Later, a new lover is introduced, but it’s the lone speaker in “Grief as Improvisation” who gives us hope, the one who can “Keep singing,” offering in “Whazup * Intact * Fine and Dandy” that “Trivial encounters of daily/ existence are in the end/ what most of life is.” Recalling those flowers on his terrace reminds us “for now/ to ladle out what you can.”

Michael Montlack

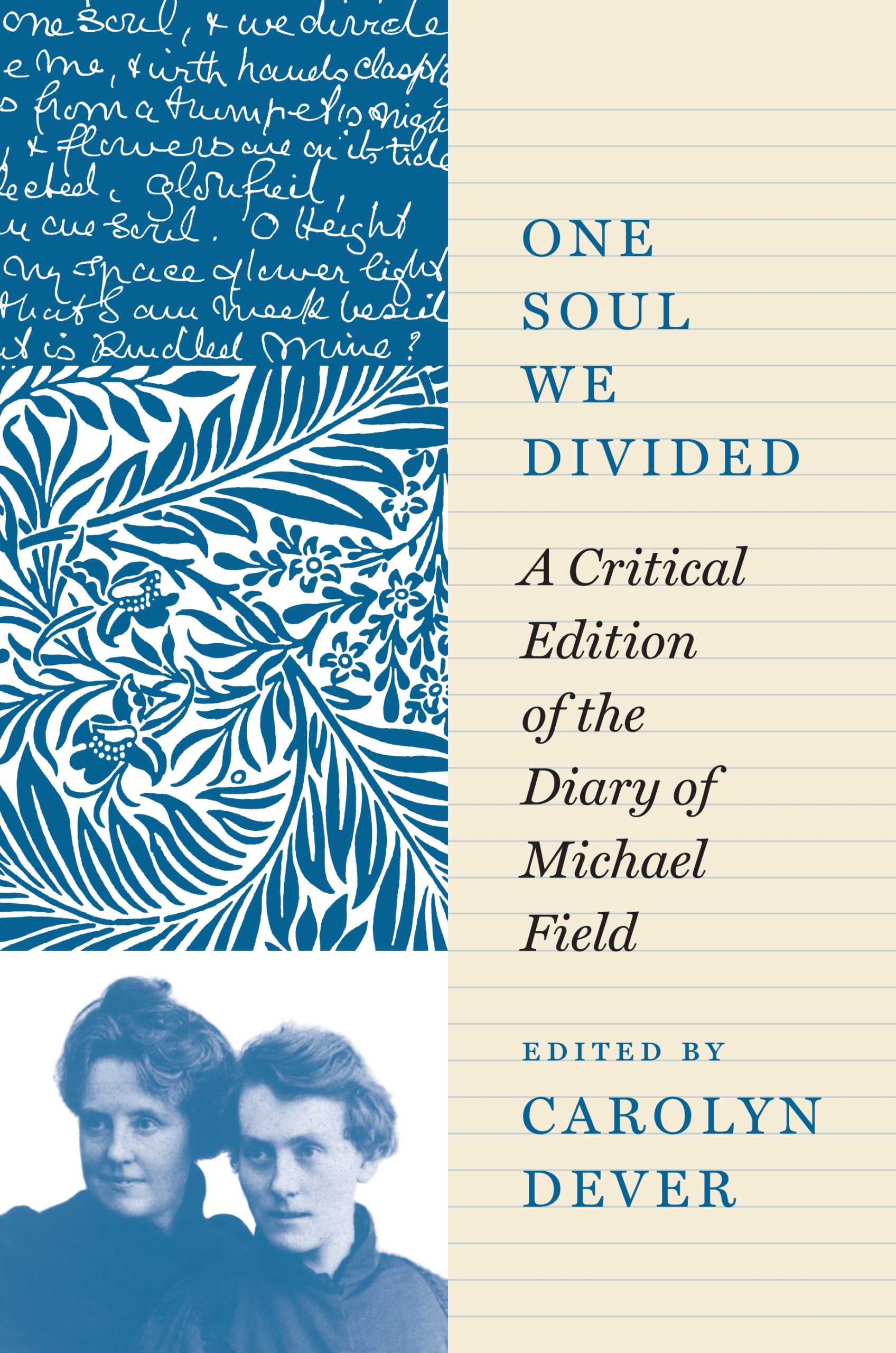

ONE SOUL WE DIVIDED

ONE SOUL WE DIVIDED

A Critical Edition of the Diary of Michael Field

Edited by Carolyn Dever

Princeton Univ. Press. 360 pages, $29.95

Michael Field was a popular Victorian writer who published fourteen plays and seven collections of lyric poetry between 1884 and 1914. And yet, the person named Michael Field did not even exist. “He” was the penname of two women who wrote together: Katharine Bradley and her niece Edith Cooper, who was sixteen years her junior and was Bradley’s longtime romantic partner. One Soul We Divided is the first critical edition of selections from the diary they coauthored, with each partner adding entries over a thirty-year period, until their deaths within a year of each other.

From the almost 10,000-page unpublished diary, scholar Carolyn Dever has selected entries that recorded important public events as the Victorian Age drew to a close, as well as private testimonials to the passion of the two women—for each other and for their artistry. Of course, unlike the male writers they knew, such as Rudyard Kipling, William Yeats, and Robert Browning, they used a pseudonym, creating a male persona in order to be published and to be taken seriously as writers. The name they chose had a more personal meaning to them: it “signified their joined identity, their intimacy, their marriage consecrated in service to poetic beauty.” Although little is known about Victorian attitudes toward lesbian relationships or incestuous pairings, it’s clear that Cooper and Bradley were far from closeted in their private lives and in their heady sphere of contemporary writers and artists.

Martha K. Davis

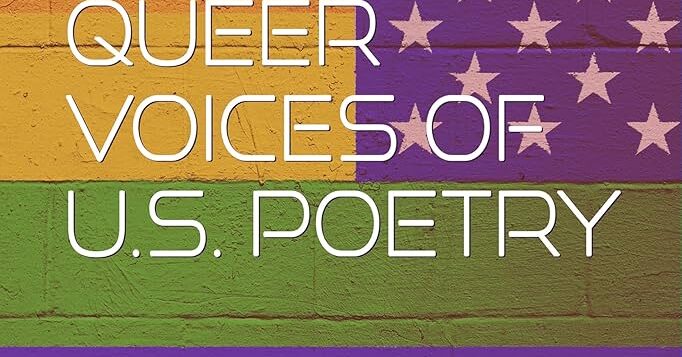

ESSENTIAL QUEER VOICES OF U.S. POETRY

ESSENTIAL QUEER VOICES OF U.S. POETRY

Edited by Christopher Nelson

Green Linden Press. 355 pages, $22.

This is a large, sprawling array of poems, an all-comers potluck rather than an well-ordered anthology. There are genuine lights here, and this volume does gather them in, so long as the reader is prepared to do a bit of sifting. The best-known LGBT poets are all here—Frank Bidart, Marilyn Hacker, Ellen Bass, David Trinidad, Mark Doty, Richard Blanco, Kazim Ali, Jericho Brown—though we only get a couple of poems from each. There is also solid work from many poets whose names are not as well-known. One such poet, Boyer Rickel, has what is perhaps the best line in the book: “The desperate will consider a boat made of ice,” a type of vessel that was actually discussed in the U.K. during World War II.

Having read the hundreds of poems in this lexical stewpot without discovering much that was distinctive, let alone memorable, I was startled into attention near the end by Michael Wasson’s unique ”A Boy and His Mother Play Dead at Dawn,” rooted in family stories from the Battle of Big Hole fought between the U.S. Army and the Nez Perce (nimiipuu) in 1877. Wasson, who grew up on the Nez Perce reservation in Idaho, captures the drama and the tension with a remarkable economy of words.

Alan Contreras

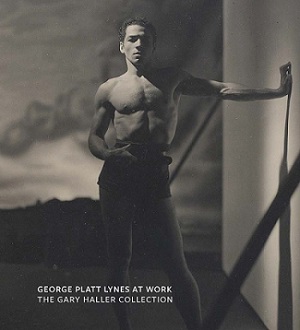

GEORGE PLATT LYNES AT WORK

GEORGE PLATT LYNES AT WORK

The Gary Haller Collection

Yale Henry Koerner Center

January 19–June 30, 2024

The catalogue for this exhibition at Yale highlights the full range of 20th-century photographer George Platt Lynes’ work. While focusing on his male nudes, it also includes a selection of his commercial work, including fashion, portraits, and dance. Also included are critical essays by Allen Ellenzweig, author of George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye (2021), and Matthew Leifheit, a photographer and editor of Matte magazine.

Ellenzweig’s essay offers an overview of Lynes’ early life, stressing his knack for making artistic and well-connected friends. He befriended Gertrude Stein while in Paris even before attending Yale. His most important relationships were with Monroe Wheeler and Glenway Westcott, two gay artists who formed a couple with whom Lynes became intimately involved (though initially he pursued Wheeler). Leifheit’s essay provides technical details on Lynes’ self-education with cameras and his unique printing and lighting techniques. He also ponders the ethical implications of photographers having sex with their models, as Lynes often did.

The sixty photographs are arranged chronologically, so the nudes are intermingled with the fashion and celebrity photos. Ballet dancers display remarkable athleticism: in Nicholas Magallanes and Marie-Jeanne, the female dancer fairly floats in midair as the male barely connects with her. Other models, including gymnasts and acrobats, pose while leaping and leaning on each other. The images reveal intimacy in all its forms, from the tenderness of the principals in Four Saints in Three Acts to the “staged sexual encounter” in the series The Lovers.

Charles Green